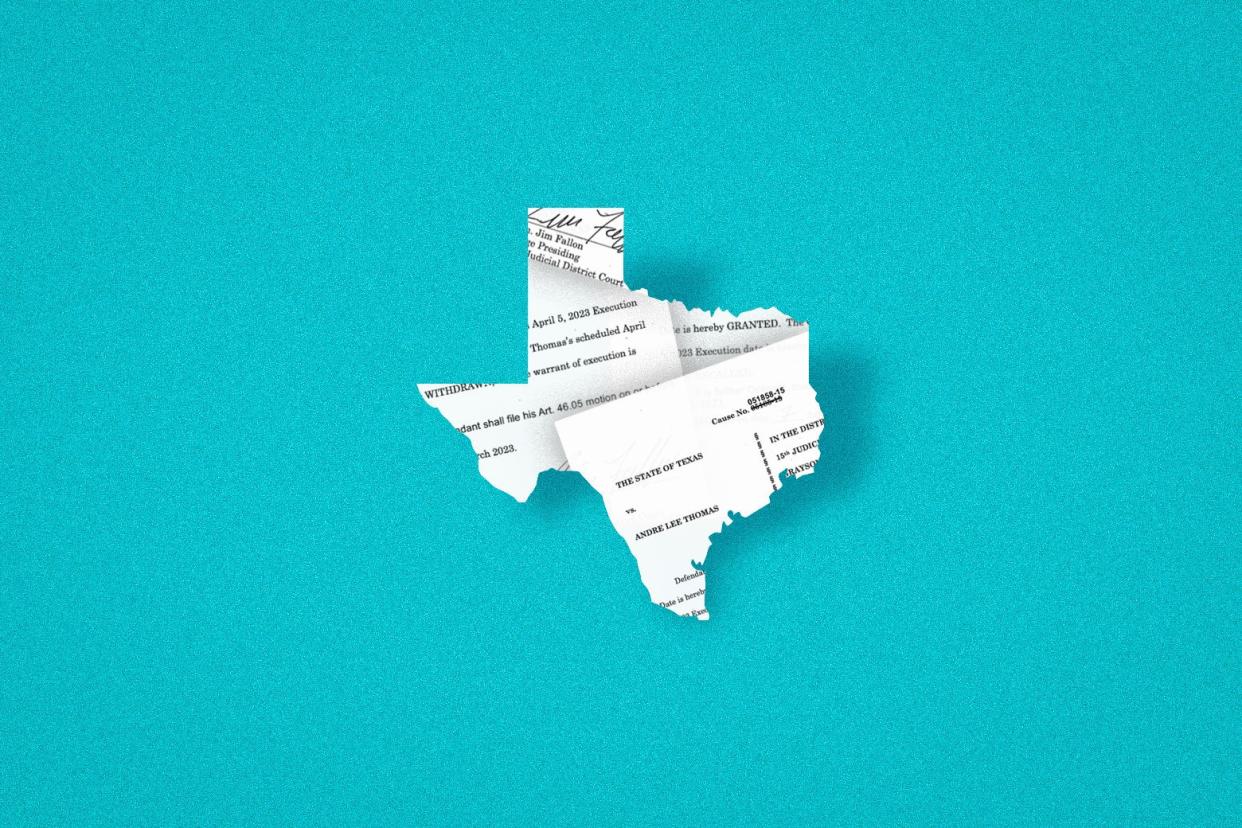

He Gouged Out Both His Eyes. Can the Government Still Execute Him?

Welcome to State of Mind, a section from Slate and Arizona State University dedicated to exploring mental health. Follow us on Twitter.

André Thomas has no eyes. One he gouged out in 2004, in jail, days after he murdered his estranged wife, Laura Boren, their son, and her daughter. The second he pulled out and ate in 2008, while on death row in Texas.

There’s no one who hears Thomas’ story and doesn’t respond with a “sharp intake of breath,” Robin Maher, the executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, told me. Thomas’ lawyers have called him one of the “most mentally ill prisoners in Texas history,” a distinction that seems to unite observers too. The details of death penalty cases are always devastating, as capital punishment is, in theory, supposed to be reserved for the most severe of murders. But Thomas’ case feels uniquely raw and excruciating.

In the 18 years since he was sentenced to death, the story of what got Thomas there has been paraded out repeatedly in courts and in the media: how he cut out the children’s hearts and a part of his wife’s lung; how he pocketed the organs and walked home from Boren’s apartment after trying, unsuccessfully, to take his own life; how, the day before the crime, he sought help at a hospital after stabbing himself. A doctor found that he was paranoid, hallucinating, and suicidal, according to court records. Thomas left the hospital while the doctor was applying for an emergency detention order, which was never carried out. Thomas, who is Black, was convicted by an all-white jury that included three members who openly disapproved of interracial marriage. (Boren was white.)

Thomas has long-standing diagnoses of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, and the delusions that characterize his illness are religious in nature and extend across decades. Following the murders, Thomas reportedly told police that he killed Boren and her two children, who he believed were connected to the devil, because God told him to do so. Now Thomas has said he believes that the state is trying to kill him because of “how important” he is to God.

Thomas was scheduled to die in April. But these delusions were concerning enough that a Texas court decided that his lawyers could have the opportunity to seek to demonstrate he is “incompetent to be executed”—that is, that he is not in a mental state to understand the reason for his execution. Earlier this month, a judge appointed the two experts—a psychiatrist, recommended by Thomas’ team, and a psychologist, recommended by the state—who will evaluate Thomas, and whose evaluations will inform the judge’s ultimate decision, in the coming months, as to whether the state of Texas can kill him.

After years of appeals, these sorts of competency proceedings often represent a last-ditch effort to avert the death penalty for prisoners with serious mental illness. With few exceptions, “success” comes only in the form of delaying an execution date (not, for example, resentencing to a different punishment). But competency proceedings serve as a microcosm for how the criminal legal system perceives mental illness, weighs responsibility, and defines justice. To understand what Thomas is up against is to understand just how far a state may push a person in pursuit of killing them.

In the U.S., it is illegal to execute someone who is “insane.” In its 1986 ruling to that effect, in the case Ford v. Wainwright, the Supreme Court cited English common law from the 1600s, which judged the execution of a “mad man” to be a “miserable spectacle” of “extre[me] inhumanity and cruelty.” Ford, who was convicted of murder in 1974 and sentenced to death in Florida, developed severe delusions about vast conspiracies against him, exhibiting symptoms of paranoid schizophrenia. He later went through Florida’s process for determining competency, which involved a 30-minute evaluation by three psychiatrists appointed by the governor. They each issued reports that determined, in broad strokes, that although Ford was suffering from psychosis, he understood the penalty to be imposed on him. The Supreme Court determined that the procedures for adjudicating Ford’s competence were inadequate, and his case was sent back down to the lower courts. Ford died on death row five years later, before the question of his own competence to be executed—and thus, according to the Supreme Court case in his name, eligibility for the death penalty—could be settled with any finality.

But what, exactly, qualifies someone as legally “insane”? Ford didn’t provide a clear answer. Twenty years later, in Panetti v. Quarterman, the court inched closer to one. Panetti, who was convicted in Texas of murdering his in-laws, also has diagnoses of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, and believes that his execution is a conspiracy, part of his long-standing “spiritual warfare with Satan” (as his lawyer put it last year). For execution in cases like Panetti’s to be constitutional, the Supreme Court ruled, the prisoner needs a “rational understanding” of the state’s reason for execution ahead of that execution being carried out. Such an understanding is required for “retributive bang for the buck,” as law professor Christopher Slobogin told me. But “rational understanding,” the court itself acknowledged, is also “difficult to define”: The justices left that work up to the states, and the patchwork of different judges within them.

Ford and Panetti establish that going forward with the execution of someone with serious mental illness can be unconstitutional. But for years, advocates have hoped that the Supreme Court would also exclude defendants with serious mental illness from ever being sentenced to death in the first place. The Supreme Court has prohibited the death sentence for other defendants: In 2002 it ruled that people with developmental disabilities were ineligible for the death penalty, and in 2005, it excluded juvenile offenders from capital punishment. But given the makeup of the court, adding severe mental illness to that list is now highly unlikely.

In the meantime, some states have taken action: Both Ohio and Kentucky have prohibited the death penalty for people with severe mental illness. (The details vary by state, but generally speaking, illnesses include schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, and delusional disorder, and the illness or associated symptoms must play a role in the crime.) Similar bills are sitting in other state legislatures, including in Arizona and Texas, but they are difficult to pass because of the polarization that surrounds the death penalty generally.

In many states, the answer to “Who can ethically receive the death penalty?” is “no one”: Twenty-three states have outlawed capital punishment, and the governors of five others have suspended executions. In the states that do enforce it, the death penalty is often carried out in a highly politized, procedurally precarious manner. An analysis by the Death Penalty Information Center found that between 1972 and 2020, “prosecutions in just 2 percent of U.S. counties accounted for half of all U.S. executions”; the top three counties were in Texas. In these counties, lawyers and advocates fight for their clients’ lives with extremely limited tools.

In theory, the line between sanity and insanity, knowledge of the consequences of one’s choices and incomprehension of the line between cause and effect, could be grounds for a rich and nuanced philosophical discussion. But the death penalty itself is a blunt, extreme punishment, and there are familiar patterns in many of the proceedings that decide whether someone is mentally eligible to suffer it. Prosecutors claim that the prisoner is “malingering”—faking their illness to avoid punishment. Mental health experts hired by the defendant’s team opine that the individual in question has a long, documented history of mental illness, including severe delusions, often religious or conspiratorial. Judges find that, sure, the prisoner is mentally ill, but not mentally ill enough. Court filings often reveal a “sliding door” moment that occurred shortly before the original crime: some interaction the individual had with law enforcement or the health care system where things could have gone totally differently, where they could have gotten help, where the future crime could have, possibly, been averted—but was not.

Put together, these patterns reveal a brutal truth: If the state wants to kill someone with mental illness, it can often find a way to do so. A 2022 article, for example, identified nine Fifth Circuit cases since the 2007 Panetti decision in which the prisoner’s competency was in question—in not a single one did the appeals court find the prisoner incompetent to be executed.

Panetti himself may be an exception—for now. Since his landmark Supreme Court case, he has remained on death row, cycling through competency proceedings. It is typical for prisoners to be stuck on death row for decades, caught in a snare of proceedings and appeals. On Sept. 27, after almost a year of deliberation following a hearing, U.S. District Judge Robert Pitman determined that Panetti was incompetent. “The Eighth Amendment,” Pitman wrote, “demands more than a single thread of arguably rational thought in a sea of otherwise disorganized thoughts and delusions to establish that a person rationally understands the reasons for his execution.”

The ruling is a victory for Panetti. But it has no sense of finality; the state can appeal Pitman’s decision. Texas could also argue, in the future, that Panetti has regained competence, and set another execution date—restarting the entire process.

For death row lawyers, any foothold against execution is still better than none. In preparing for his competency evaluation, Thomas’ legal team pursued a risky strategy in hopes of ultimately getting their client more humane treatment. In court filings, they argued that Thomas should stop taking all antipsychotic medications prior to being evaluated by experts so that they could assess his rationality at a baseline, unmedicated state. This was a desperate effort to ensure that Thomas has the best chance of being deemed incompetent by the experts, and later the judge, but it also illustrates a clear dilemma: Would it be safe for Thomas to be taken off medication? Could we trust the Texas prison system to keep someone experiencing an episode of psychosis and self-harm safe?

It’s an example of what Maher called the “perverse choices” tied up in the death penalty. For lawyers, doctors, and others who walk through the capital process, this is a hard truth: Attempting to avert someone’s death can have excruciating consequences for their lives.

In the absence of more robust state laws or guidance from the Supreme Court, we are left in a sort of purgatory where people spend decades cycling through court procedures that broadcast the intimate details of their mental health crises to varying levels of decisionmakers, while their lawyers are often forced to weigh what would be best for them medically against what’s most strategic legally. Victims’ families, too, are brought before courts again and again, their pain stretched out over years with little resolution. Tax dollars disappear in a black hole of expert fees and attorney hours. Usually, the outcome is the same. In Ford, the Supreme Court decided that executing a person who is extremely mentally ill would be a “miserable spectacle,” saying we owe them a process. But we have, decades later, not managed to move beyond spectacle.

Thomas will soon be evaluated by the two court-appointed experts tasked with determining whether he understands that “he is to be executed and that the execution is imminent,” and the reason for the execution. Some argue that these standards, established by Texas state law, are more simplistic than the standard laid out by the Supreme Court in Panetti. But Thomas’ fate will ultimately depend on the court’s understanding of what he understands. It is a shaky series of questions on which to stake someone’s life.

In setting the conditions for Thomas’ evaluation, the judge ignored the request for him to be unmedicated. As it stands now, he will stay on his treatment.

According to court records submitted by his attorney in July, when asked what would happen if the state did execute him, Thomas said, “They can’t kill me, that’s the thing. They can’t.” He reportedly posited he would end up with brain damage but wouldn’t die. “I’d be locked,” he continued, “inside a room inside my mind.”