Gov. Evers boosted school funding for 400 years. Why some school leaders aren't impressed

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

MADISON - A public school funding increase for the next four centuries drew national attention to Gov. Tony Evers' veto powers, but district administrators aren't confident the move will hold up, much less eliminate the possibility that they will need to turn to referendums in the future.

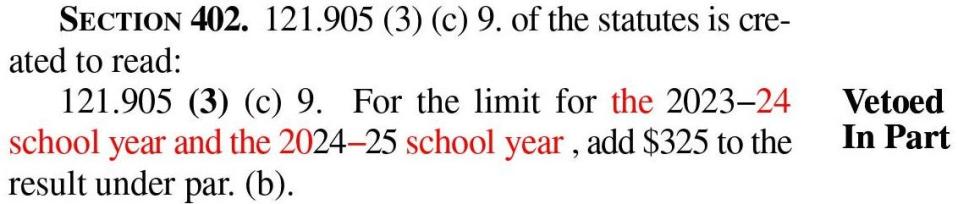

Wisconsin's new budget raises the state-imposed limits on what school districts are allowed to collect by $325 per student per year, until 2425. Evers used his veto pen to remove a hyphen and a "20" from a reference to the 2024-25 school year to keep the funding mechanism in place for the foreseeable future.

Evers sought to provide a revenue limit increase "in perpetuity" after years of no increase, and "in the process respond to complaints from school officials that previous freezes left their budgets to be eroded by inflation, particularly during the rapid rise in consumer prices over the past two years," a report from the nonpartisan Wisconsin Policy Forum notes.

Public school leaders are less than ecstatic about the veto, pointing out a few caveats. First, lawmakers could override the plan. Second, the $325 per student still falls short of current inflation. And third, while the move allows school districts to raise more funds, it doesn’t guarantee state funding to cover the bill, potentially leaving local school boards to decide whether to raise local taxes or miss out on the increase.

"When we're living in these communities where we understand that our families are already struggling, it's hard for us to make the decision to go ahead and raise their taxes every single year, just because we have the authority to do it," said Glenda Butterfield-Boldig, administrator of the Bowler School District in central Wisconsin.

Lawmakers provided state funding and tax credits to offset the local school levy tax impact of the $325 per-student increases over the next two years. Beyond that, if lawmakers don't provide more aid in the next budget cycle, districts could increase local taxes by an estimated $260 million in 2025-26 and $520 million in 2026-27, according to a memo this week from the Legislative Fiscal Bureau.

Evers, in his budget plan, had proposed a $350 per-student increase in 2023 and an additional $650 the following year. Lawmakers deflated those amounts and added larger increases for private and charter schools.

A spokeswoman for Evers did not return a request for comment in response to administrators' concerns that the increase would not meet their budgetary problems.

Veto could be overturned through lawsuit, future budgets

Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester, has said he's gearing up to sue over Evers' move, but Senate Republicans have not yet said whether they're on board. The veto could also be overturned through legislation, including a future state budget, a constitutional amendment or a veto override in the Legislature.

The report Wisconsin Policy Forum notes that even if the veto is upheld in court, it could be changed by future governors and legislators.

"Yet it does make it more likely the revenue limit increase — equal to about 2.7% in the current school year — would continue through the 2026-27 school year and potentially beyond that period if Evers serves another term or is replaced by another Democrat," the report says.

School administrators, doubtful that the funding increases will stay in place beyond 2025, are not yet ready to overhaul their budget projections.

"We'll see where that (veto) ends up," said Renae McMurray, administrator of Mercer School District in northern Wisconsin. "I'm not planning out beyond the next two years with that $325 increase; we'll see where that goes. It would be nice to know that we had additional funding going beyond the next couple years, but we'll see where that lands."

While Nathan Hanson, administrator of White Lake School District, also in northern Wisconsin, said his initial reaction was that the veto would be repealed at some point, he expects the increase will bring some predictability, especially as more districts face going to referendum.

"We could actually do some really long-term planning in terms of budgeting," he said. "It's very hard to do that in school districts because every two years, the whole landscape of funding can totally change based on what the state budget is."

Tarik Hamdan, chief financial officer of the Kenosha Unified School District in the southern part of the state, was skeptical the increase would hold beyond two years and worried that the "four-century" headline may lead voters to think schools are better positioned than they really are.

"It was a nice gesture symbolically but it does kind of convolute the conversation with the public," he said. "They won’t necessarily keep up with the news when this gets reversed."

Even with increase, schools still face going to referendum

The $325-per-student increase may not be enough to keep pace with inflation, according to estimates from the Legislative Fiscal Bureau.

It also doesn't compensate for the 14 years that school districts have gone without inflationary increases. Just over the past two school years, the bureau calculated inflationary increases would have been $715 per student, while schools got zero.

Some school districts have made up some of the difference by turning to their local voters with referendums. If voters in a school district approve, districts can collect additional taxes to fund specific projects or ongoing operations.

But if they fail, there are consequences. After a failed referendum, school districts are barred for three years from benefitting from state increases to the minimum funding levels allowed for schools. As part of the new state budget, lawmakers bumped that minimum from $10,000 per student to $11,000 per student.

"I foresee this being a huge problem," said Willie Garrison, superintendent of the Beloit School District, which had a narrowly failed referendum earlier this year. "Three years is a long time for a school district not to see that type of increase. It hurts us tremendously; it definitely needs to be changed or looked at at the state level again."

The School Administrators Alliance and the Wisconsin Association of School Boards said in a statement after the budget's signing that inflation is at "historically high levels" and districts may still have to go to referendum, even with the revenue limit increases. Some of those rising costs include teacher salaries and healthcare benefits.

In the meantime, districts are looking closely at their budgets and considering their chances.

Under the increase, the Adams-Friendship Area School District in central Wisconsin could use an additional $400,000 each year, but that does not eliminate the possibility of going to referendum again. Before this increase, districts were only able to raise their revenues about 0.2% over the past decade, business manager Brian Krey said.

"The $325 helps tremendously this year, but it doesn't undo what hasn't been done for the last 12 years. And that's why you've seen so many operational referendums," Krey said. "If this $325 had been done a decade ago, I don't think you would have seen as many, maybe still some. It's been tough to operate with that little of increase on an annual basis."

In Kenosha, Hamdan said a referendum is "something the board always has up for consideration." The school board already decided to close an elementary school to save money. It is also cutting 15 teaching positions and using federal pandemic relief funds to pay for over 110 staff who are helping students with reading, math and mental health. Those funds expire after this school year.

MPS says state budget only means $12 more per student

Milwaukee School Board member Missy Zombor, on Twitter, called the veto a “stunt to distract you from how badly this budget fails our children and public education,” arguing the $325 per-student bump will not be as consequential as it might seem.

For Milwaukee, the bump will provide only an extra $12 per student in the 2023-24 school year, and about $38 per student the following year, according to initial estimates by MPS Chief Financial Officer Martha Kreitzman.

That's because usually, like other districts with severely declining enrollment, MPS gets a funding cushion that delays associated drops in funding. With the additional $325 per student, the overall funding drop is less dramatic and so the funding cushion is also less — leaving the district with a smaller net impact from the bump.

"The state budget was good for taxpayers, and that's not a bad thing, but it wasn’t necessarily helpful for our K-12 students," Kreitzman said.

Kreitzman said the bump won't be enough to make significant changes to MPS' budget, including the plan to leave hundreds of positions unfilled.

Other districts, including Beloit, are in similar positions, seeing a lesser net impact on their budgets.

"That $325 isn't really a true $325 for school districts. Some school districts will receive the full benefit of the $325 increase in each year. Some school districts, like Beloit, will receive a very minimal amount of that," said Bob Chady, the business manager of the Beloit School District.

The Madison Metropolitan School District will be allowed to collect an additional $5.5 million thanks to the $325 per-student bump, while it otherwise would have collected $3 million to compensate for funding drops. MMSD Assistant Superintendent of Financial Services Bob Soldner said it's better for the district to get the bump to the revenue limit, as opposed to the compensation for funding drops, as it's more sustainable.

Still, the $325 amount doesn't make up for years of losing to inflation and declining enrollment. He said the school board is considering asking voters for another referendum to allow the district to raise taxes further. The district is already planning to cut about 156 full-time staff positions, including about 84 teacher positions.

More: Why some schools will win bigger than others under state budget passed by lawmakers

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: What Gov. Evers' 400-year veto move means for Wisconsin school funding