Government’s crackdown intensifies in Cuba weeks ahead of a planned opposition march

Cuban authorities have threatened organizers of a pro-democracy march called for November with legal charges, while conducting a vast security operation to intimidate ordinary Cubans who express support of the initiative or criticize the government on social media.

Members of the civic group Archipiélago notified authorities of its intention to march on November 15 to advocate the respect of civil liberties and to call for the release of political prisoners and hundreds of protesters still detained after an islandwide uprising on July 11. The group, created by young artists, professionals, activists and longtime dissidents, said the Cuban Constitution allows peaceful demonstrations.

Cuban authorities interpreted the Constitution in different terms, calling the march “illicit” and a regime change plot backed by the United States and Cuban exiles.

On Sunday, Cuban leader Miguel Díaz Canel said the planned march was not a “civic act but an act of subordination” to the U.S., which he accused of planning the initiative to “subvert” the internal order.

“The declared objective of the U.S government is to overthrow the Cuban Revolution,” Díaz-Canel said during a Communist Party meeting on Sunday. “We are prepared and willing to do anything to defend what is most sacred, what unites us; to be consistent with the invariable decision of Homeland or Death, Socialism or Death.”

Last Thursday, the General Attorney’s office said in a statement that if Archipiélago members move ahead with the march, they will face serious charges, including “disobedience, illicit demonstrations, instigation to commit a crime or others foreseen and sanctioned in the current criminal legislation.”

The government is also using its security forces and state media to push the same message. In the past several weeks, state media outlets, including the country’s largest newspapers and television channels, have been discrediting the young activists by portraying them as mercenaries paid by organizations connected to the U.S. government — accusations they have denied.

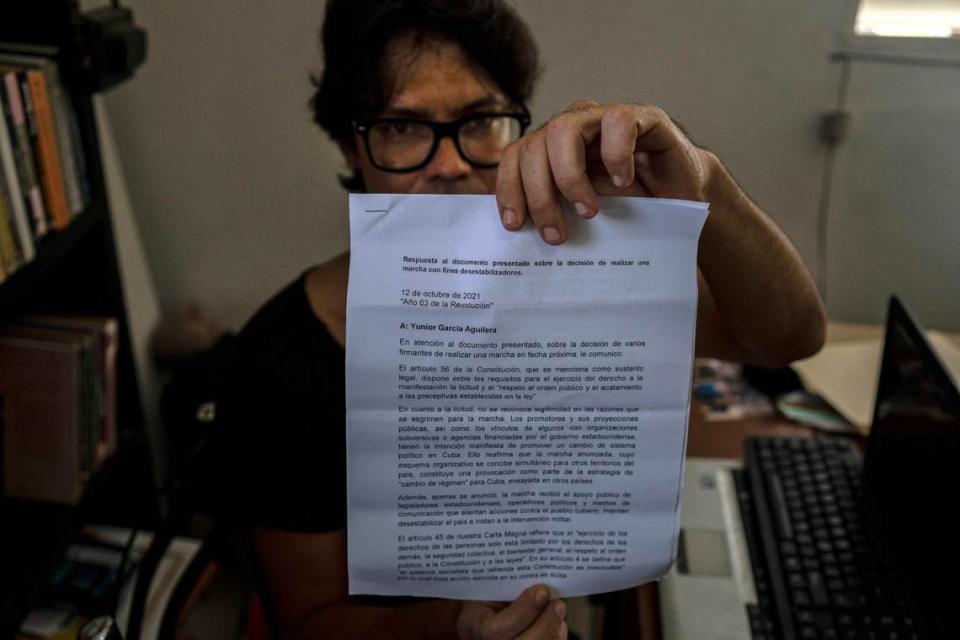

“Monolithic thinking, censorship, and political persecution have been the bread and butter for Cubans who do not submit to the control of their masters,” said actor and playwright Yunior García, one of Archipiélago’s leaders in a statement. “No one would be such an idiot to face all this (and the fury to come) for money. We do it out of convictions, and that gets those in power desperate. Nor does anyone give us orders from anywhere.”

Meanwhile, state security, the intelligence agency controlled by the Ministry of Interior, has been conducting an islandwide operation to intimidate members and supporters of Archipiélago, according to interviews conducted by the Herald and information shared on social media.

The repressive actions reported include short arrests, fines, citations to a police station for interrogation, cuts in the internet and phone services, repudiation acts, prohibitions to travel abroad, harassment to family members and job firings. And there is at least one report of a brief kidnapping.

Leinier Cruz Salfrán, a march planner in Guantánamo, an eastern province, was fined 3,000 Cuban pesos because authorities said videos he published on social media violated the “internal order” as stipulated in the decrees 35 and 370, he said in an audio message shared with the Herald. Both decrees have been widely criticized as curtailing civil liberties and freedom of expression.

Cruz Salfrán said after he left the Ministry of Communications office where he was fined on Friday, state security officials told him to get into an old Russian car for a “talk.”

“They asked for my phone, and I gave it to them; I would not resist,” he said. “Two people that I assumed were also state security agents got on the backseats beside me. Immediately after, they forced me to lower my head, and they hooded me. I know it is better not to resist this sort of treatment, but I struggle a bit because they wanted to choke me, which gives me nausea and makes me feel very sick.”

The activist, targeted because he notified authorities of the march in Guantanamo, said the agents took him to an unknown location where he was threatened during an hour-long interrogation.

“I will not give more details, so I don’t transmit the message they want to promote,” he said. The agents later dropped him near his home.

Several members of Archipiélago are under surveillance at home. García had his home entrance vandalized with dead animals. And two doctors connected to the group, Manuel Guerra and David Martínez, were fired from their state-paid jobs.

An intimidation campaign

But as frustration with the Cuban regime grows, it is not only the pro-democracy activists but also a larger swath of the population having firsthand encounters with the repressive apparatus. The government is particularly nervous after the protests in July, and the march’s plans have shown discontent is widespread.

The tactics are not new and have been deployed throughout the decades against political dissidents, independent journalists, and lately, against young artists. But in the past weeks, social media influencers and generally anyone who expresses an opinion against the island’s authorities have become a target.

Rafael Santos Regalado, a young Cuban software engineer living in Havana, had never been in a police station until earlier this month. There, state security agents warned him against posting political content on social media, including what they thought were manipulated images of a young Fidel Castro seated and looking at the camera, a pile of dollar bills laying at the table in front of him.

The images were authentic, taken at a fundraiser with Cuban emigres in 1955 in New York. Santos tweeted them to question accusations by government officials that the organizers of the march are receiving financial support from Cuban exiles.

“I am NOT a criminal; I am NOT a terrorist, freedom of expression is a RIGHT that I will never renounce,” he said on Twitter before attending the interview with the officers.

Santos was fined 3,000 Cuban pesos for promoting the march and let go. Thanks to his social media followers on the island, he got the money to pay it in less than an hour. He and other young activists celebrated on Twitter. Then he was summoned again by the police. This time, the threats were blunter, he told the Herald.

“They told me that if violence erupts on November 15, they will blame me because they said I was promoting violence,” he said.

Jonathan Valdés Vega, 32, a tech technician who administers a large Facebook group of iPhone users in Cuba, was also interrogated by the police in Havana earlier this month, he said in an interview. He believes someone informed authorities he was trying to make personalized T-shirts to wear during the march. He said state security agents were particularly worried that he would share political content with his thousands of followers.

Even a “like” can get a Cuban in trouble. Caridad Otero, a 60-year-old pensioner living in Camaguey in central Cuba, was threatened with charges for “liking” political content on Facebook, according to legal aid organization Cubalex.

The crackdown is unfolding in real time on social media.

En el día de la defensa en Cárdenas ponen a miembros de un CDR con empleados de la Biblioteca Municipal a protagonizar un circo de enfrentar un supuesto ataque con palos de manifestantes en #Cuba. Así le miente a los cubanos la dictadura sobre el #15NCuba. De: Beatriz Duquezne. pic.twitter.com/RaKIGUZzF5

— Rolando Nápoles (@RNapoles) October 25, 2021

“They are trying to use the same repression techniques before social media changed things, and it’s obvious they don’t understand how they work, they don’t have tools to deal with the social media revolution,” said Saily González, a Cuban entrepreneur who became one of the more visible voices of Archipiélago. “Every time they harass someone, that’s another family that realizes that one cannot live without rights.”

In an interview from Santa Clara, she said young Cubans who have created communities on social networks like Twitter now support each other more. She cited the quick crowdfunding effort to pay for Santos’ fine and the recent release of doctor Guerra, the Archipiélago member who was fired, after several social media users denounced his arrest earlier this month.

González was herself the subject of a repudiation act near her house. She decided to close her cafe Amarillo B&B in Santa Clara because she feared state security would use her private business to retaliate against her and her employees because of her activism.

“Being an entrepreneur and activist should not be a danger to the people around you,” she said on Twitter, adding her business will reopen when “freedom of thought and expression of all Cubans are respected.”

But the government has made clear it would not tolerate dissent. Last week, a man who protested against the government on July 11 was given a 10-year sentence. Others face charges that could lock them up in prison for up to 25 years.

Images of state workers and members of the CDRs, a neighborhood surveillance organization, armed with clubs, baseball bats and what appear to be old Russian guns rehearsing to confront would-be protesters, are circulating on social media, another dire warning to those considering attending the march.

Díaz-Canel, who faced criticism for inciting government supporters to confront July 11 demonstrators by any means, said Sunday the Cuban Constitution, which establishes socialism is “irrevocable,” calls on citizens to do just that.

“Citizens have the right to fight by all means against anyone who tries to overthrow the political, social, and economic order established by the Constitution,” he said.