Government redlining of Topeka reverberates 100 years later through food deserts, health outcomes

White and Black Topekans experience significantly distinct realities to this day due, in part, to explicitly racist federal policies first implemented nearly 100 years ago.

The effects of redlining on Black and immigrant neighborhoods in East and North Topeka between 1935 and 1940 reverberate in health outcomes in these neighborhoods.

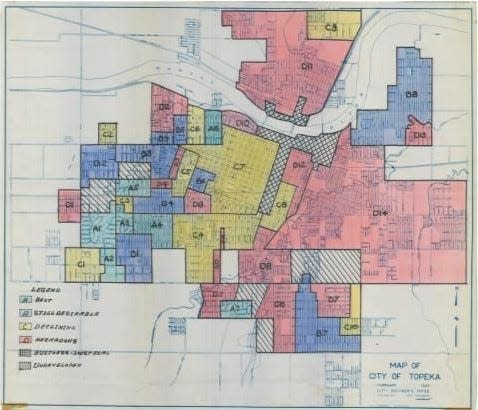

Beginning in 1935, federally authorized housing discrimination by the Home Owners’ Loan Corp. shifted the way in which Topeka, and many other cities across the nation, would develop by fueling investment in white neighborhoods and disinvestment in Black and immigrant communities.

The HOLC, created in 1933 by Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, fueled pre-existing privatized housing discrimination by labeling, or redlining, less white districts as declining or hazardous and advising against public and private investment.

East and North Topekan neighborhoods were singled out to be redlined by HOLC staff who, using data from local real estate professionals, discouraged investment in predominantly Black and immigrant communities.

Districts like East Topeka, with high densities of Black or immigrant residents, were designated as a “hazardous” investment zones with “significant negro concentration” where lenders should “refuse to make loans.” Governmental authorization to refuse to insure mortgages in and around black communities served a clear function in enforcing racial segregation.

While redlining began in the 1930s, preventing nonwhite Topekans from attaining mortgage financing and becoming homeowners, it continued until the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968. During that 30-year span of disinvestment in Black neighborhoods, inequities beyond homeownership rates developed across Topeka.

Today, Topekans living in formerly redlined neighborhoods are more likely to be food insecure and have a shorter life expectancy. These inequities are strikingly mapped along the same lines as the redlining of North and East Topeka.

Many of the same neighborhoods that were redlined in Topeka are now classified by the USDA as food deserts, areas where people have limited access to healthy and affordable food.

In large portions of East and North Topeka, residents must travel more than a mile to the nearest grocery store. Proximity to grocery stores is a well-documented predictor of health outcomes, as communities in food deserts have been shown to experience higher rates of obesity and death from cardiovascular complications and cancer.

East Topeka, however, wasn't always a food desert. Jack Alexander, Topeka’s first Black city commission member and former president of the Kansas Historical Foundation, remembers it differently.

Alexander recalls growing up in an East Topekan Black community with a robust array of Black-owned grocery stores, businesses and other public goods. When Alexander returned in 1956 after serving in the Navy, he found many of East Topeka’s Black-owned institutions decimated. A thriving Black neighborhood now had far more boarded up Black-owned grocery stores and businesses than he’d remembered.

Decades of disinvestment in redlined areas of Topeka had finally caught up to its Black community.

Beyond food deserts as predictors of poor health outcomes in formerly redlined Topeka neighborhoods, life expectancy rates are significantly lower in once redlined Topeka neighborhoods.

Topeka census tracts with the city’s lowest life expectancy rates significantly overlay with redlined districts. The Kansas Health Foundation found that disparities in Topekans’ average life expectancies today overlayed significantly with 1930s redlining maps.

The geographically largest redlined district was East Topeka’s District 14, described by the HOLC as hazardous due to its makeup of “a variety of foreigners and negroes.” Today this area includes six census tracts with the many of the city’s lowest life expectancy rates. Redlining’s effect on Black Topekans remains disproportionate.

In 2018, Kansas-based racial justice group Communities Creating Opportunity hosted a series of community dialogue sessions to talk about forces of structural racism including the city’s history of redlining Black and immigrant neighborhoods.

These meetings began a community-wide dialogue akin to what former city commission member Alexander has called for: “wholistic conversations” addressing segregation and redlining in Topeka in order to “balance the scales” and address nearly a century of inequity since redlining maps were drawn.

Henry Wolgast is a master’s student studying urban affairs and public policy at the University of Delaware.

This article originally appeared on Topeka Capital-Journal: Government redlining of Topeka reverberates nearly 100 years on