They graduated during segregation. Carver’s first class reflects on school’s legacy of love

When he addressed the Columbus Municipal Auditorium crowd 60 years ago as the keynote speaker at the first graduation ceremony in Carver High School’s history, Leroy Johnson, the state senator from Fulton County then, put the momentous moment in perspective.

“This is the first time in 92 years that a Black man has sat in the Senate of Georgia,” Johnson said. “Negroes are realizing their vision, their hope, their ambition.

“We live in a state where the Negro is saying, ‘Lord, we ain’t what we want to be, and we ain’t what we ought to be, but thank God we ain’t what we was.”

Speaking to Carver’s 139 graduating seniors, Johnson said, “Whatever area you decide to go into, whatever you plan to do, you decide you are going to be a leader.”

Six decades later, this class — born and graduated during racial segregation — lived up to that challenge.

They distinguished themselves as honorable citizens with productive careers, contributing to their country and community in the military, healthcare, education, law, government, business and ministry.

This week, as 39 of those classmates gather in Columbus for their 60th reunion, the Ledger-Enquirer features four of them as examples of their positive impact. And they credit Carver for helping to equip them for their journey.

Despite the U.S. Supreme Court outlawing segregated schools in 1954, the Muscogee County School District didn’t integrate until a 1971 court order dismantled its dual school system after MCSD’s 1963 “freedom of choice” plan failed to integrate the district enough.

Named in honor of George Washington Carver, the prominent African American agricultural scientist and inventor, the school opened in 1954 as a junior high school for grades 7-8. It later was expanded, and grades were added, until it became the city’s second high school for Black students, joining rival Spencer, and producing that first graduation class in 1963.

Wilma Griffin Johnson, Clevie Gladney Covington, William Crawford and Johnnie Jackson were among them. From their interviews with the L-E, it’s clear they didn’t need that state senator’s graduation exhortation to seek and achieve laudable lives. They already had continually heard such motivational messages from Carver’s caring faculty and staff.

Here are pieces of their stories:

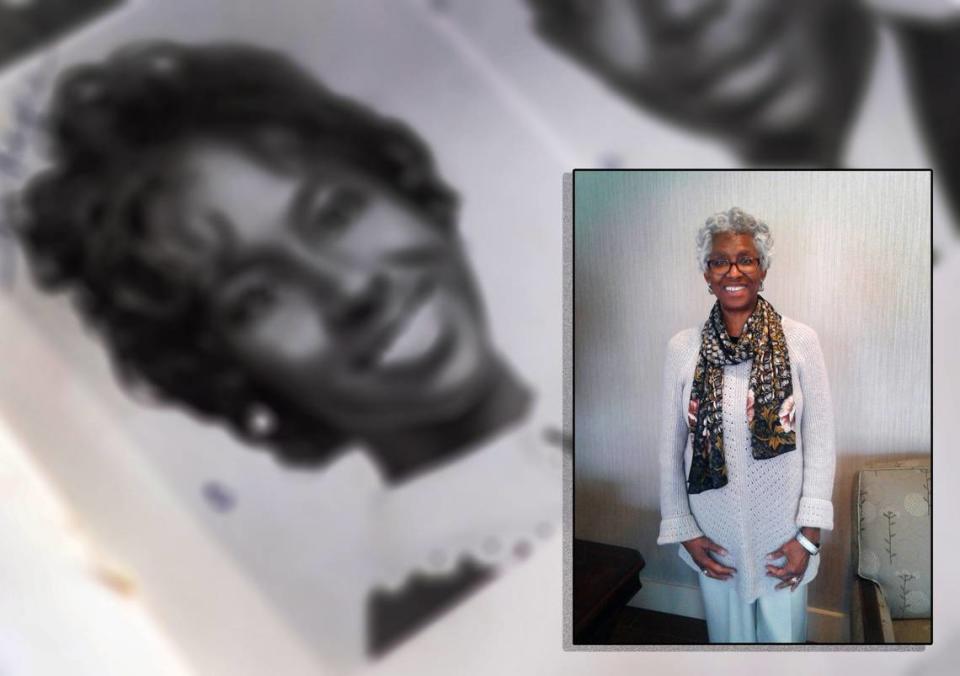

Wilma Griffin Johnson

Johnson, 77, was the Class of 1963 valedictorian at Carver. No wonder classmates voted her as Most Likely to Succeed.

She earned a bachelor’s degree in math from Bennett College and a master’s degree in public health the University of North Carolina. She worked for 32 years at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, retiring in 2002 as associate director for minority health.

Now living in Atlanta with her husband, Raymond, they have one daughter and three grandsons.

Raymond, who served for three years in the U.S. Army and became a self-employed home improvement worker, also is a 1963 Carver High graduate. They met in fourth grade at Carver Elementary School.

Carver’s faculty and staff “helped me feel valued,” Johnson said. “… This was the time of the Civil Rights Era, and we were empowered, encouraged to do more and go further. I felt I could do and go wherever I wanted.”

Between her junior and senior years, Johnson earned a free summer course, sponsored by the National Science Foundation, at the University of Buffalo. She was the only Black student in the class of about 20 students, and it was the first time she traveled beyond Georgia and Alabama.

“I did just as well as the students who came from larger schools,” she said. “… It was a huge boost of confidence. After being told (by segregated society) you are second class, when you have an experience like that, it really impacts your outlook.”

Johnson was a Carver cheerleader. Her favorite cheer: “There’s a thrill on the hill.”

The area around the school in the Carver Heights neighborhood is known as The Hill. And it indeed was a thrill for Johnson to learn there — even when she got in good trouble, speaking out and standing up against what she believed was wrong.

Johnson was among a dozen students who boycotted a school dance because they thought it was unfair for a sophomore to be elected queen instead of a junior or senior. As a result, principal S.P. Charleston took away the boycotters’ privileges for not supporting the school.

“Looking back, he was right to say what he did, but I still fee like he shouldn’t have taken us down,” Johnson said. “But I respected his authority.”

Clevie Gladney Covington

Covington, 77, was the Carver Class of 1963 salutatorian. No wonder her classmates voted her as Most Studious.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in math from Stillman College, she taught for one year at Arnold Junior High School in Columbus before joining one of her sisters in Washington, D.C., where she worked for 10 years as a mathematician at the U.S. Department of Agriculture and for 25 years as a statistician at the U.S. Department of Education. She retired in 2005.

Covington now resides with her husband in Temple Hills, Maryland. She feels compelled to attend the reunion, reconnecting with her marvelous memories of Carver.

“I enjoy talking to people I haven’t seen in years,” she said. “… The teachers really cared about you. They took time to make sure you knew whatever it was they were trying to teach you.”

Her favorite was Mr. Hendricks, a math teacher who was stern but stayed after school to help students.

“He was there for you,” she said.

Although she forgets her favorite substitute teacher’s name, Covington remembers his advising mantra: “Start low. Aim high. Strike fire. Then retire.”

Covington also appreciates Charleston’s strict enforcement of the school’s dress code. Girls had to wear dresses that covered their knees, and boys couldn’t wear the colorful pants that were in fashion at the time.

“Charleston was having none of that,” she said with a laugh.

Overall, the Carver faculty and staff instilled in her that discrimination meant she had to study harder and work harder to be considered as worthy of recognition as anybody else.

“I think they did an excellent job preparing us,” she said.

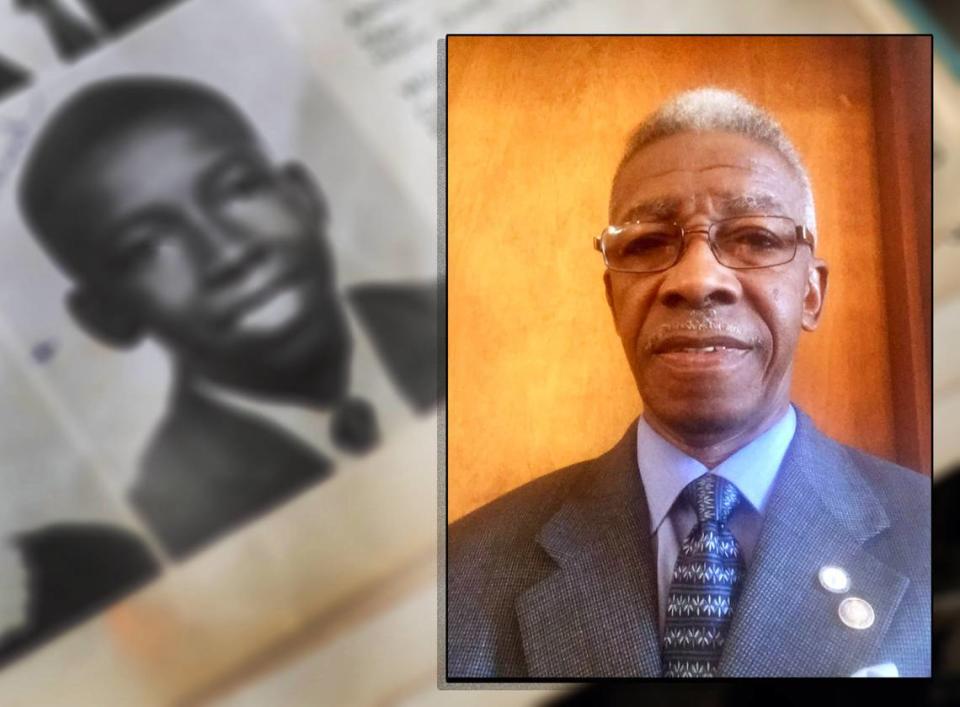

William Crawford

Crawford, 78, was voted Most Artistic by his classmates. He continued that reputation as an adult.

He earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from North Carolina A&T — the first person in his family to graduate from college — and a master’s degree in education from Columbus College.

Crawford taught art for 32 years combined at Spencer and Baker before retiring in 2000. Then he worked as a youth counselor and a specialist in the city’s job training program before retiring again a few years ago, although he still works in the program during the summer.

Crawford, divorced, resides in Columbus and runs a home-based sign shop as a graphic artist and photographer. His daughter and grandson are in Atlanta.

As the editor of Carver’s newspaper during his senior year, Crawford won journalism awards on the state level and from the Ledger-Enquirer.

Crawford called Carver “a place that overflowed with love and concern for students.”

Ms. Watt personified that description. Crawford recalled this teacher “seeing to it” that an impoverished student had the resources he needed to graduate

Crawford quoted Charleston’s oft-repeated words of correction — “We can’t have this at Carver. Our students just don’t act like that.” — when disciplining students.

“He wanted us to strive to do great things and be good people,” Crawford said.

Crawford also cherishes the influence of John Washington, the debonair assistant principal at Carver then, who inspired him to attend his alma mater, North Carolina A&T.

“He was cool, calm and collected,” Crawford said. “… He knew how to talk to us. He never raised his voice, but whatever he got across just flowed out of him smooth and mellifluously.”

And he delivered substance along with that style.

“He instilled in me and a lot of guys values like integrity, and he wanted us to excel,” Crawford said. “… Being a new school, with Spencer already having an established reputation, we didn’t want to be second rate. … We didn’t want to be a shortcoming to the city.”

When it came to deciding which team to support while Carver and Spencer played against each other, Crawford cheered more for Spencer while he taught there because that was the source of his paycheck. Now in retirement, he said, “I root for both schools.”

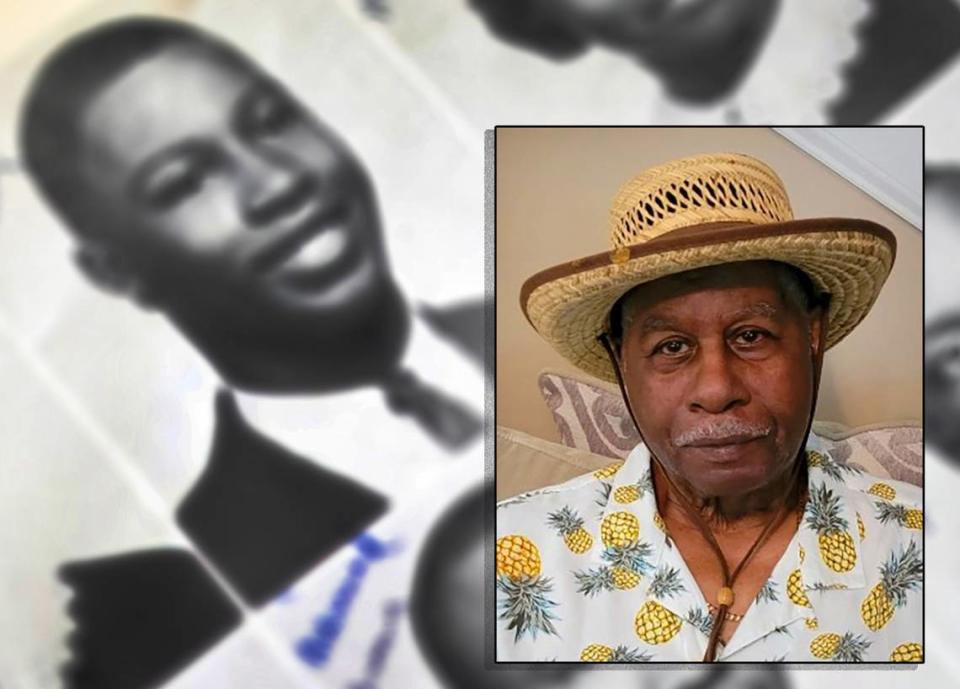

Johnnie Jackson

Jackson, 78, was voted by his classmates as Most Dramatic, but the kind of drama he experienced as an adult came not on stage but through his careers in the military, law enforcement, ministry and education.

After high school, Jackson served in the U.S. Army for 20 years, attaining the rank of sergeant first class. He worked for 32 years in crime prevention and community relations at the Columbus Police Department, including 15 years as its first Black chaplain, helping organize the Neighborhood Watch program and the Junior Police League.

Jackson also has been a substitute teacher and security officer for MCSD. In retirement, he serves as an elder and prison ministry volunteer with Body of Christ Church International.

He earned an associate’s degree in theology from Christian Life Seminary, a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice from Columbus College and a master’s degree in police administration from Troy State University.

Married to his third wife for 12 years, Jackson resides in Fortson and has two children and four grandchildren.

Jackson is proud of Carver’s heritage.

“It’s been a school that really is concerned about education and making sure that we graduate and have good character and treat everybody the way they’re supposed to be treated and just love people,” he said. “We still love each other today, including the instructors. It’s amazing how the love has stayed and never broke.”

Watt also was one of Jackson’s favorite teachers.

“She was like a mama to us,” he said. “She would make sure we could succeed and not have to worry about flunking out. … She helped some students who couldn’t afford lunch or didn’t have rides to school.”

And when he misbehaved — such as pulling bows from girls’ hair — the “big paddle” from the industrial arts teacher, Mr. Wright, soon would set him straight him.

“When he spanked,” Jackson said with a laugh, “that wasn’t no joke.”

As he reflected on his years at Carver, Jackson offered advice for the school’s current class of seniors.

“Remember that we are not here forever, so therefore we must get ourselves in order,” he said. “… Let’s pray for each other and love each other.”