Grand Slam club still off-limits to Rory McIlroy as Masters cuts him loose | KEN WILLIS

It was 30-some years ago and Jose Canseco was becoming baseball’s first 40-40 man — 40 homers and 40 stolen bases in the same season.

Mickey Mantle was asked what he thought of Canseco’s 40-40 chase.

“If I knew it was gonna become such a big deal,” the Mick drawled, “I would’ve done it myself.”

The revisionist historian in us (some of us, anyway) makes you wonder how many others would’ve been in golf’s “career grand slam” fraternity if they knew how history treats such gents.

In recent years, as well as this year, when Masters week arrives, much is made of Rory McIlroy’s desire to add a Masters victory to his four combined wins in the U.S. and British Opens and PGA Championship.

Not happening this year, of course, but someday Rory could become the sixth, joining Gene Sarazen, Ben Hogan, Jack Nicklaus, Gary Player and Tiger Woods.

But remember, for roughly half of the history of championship golf as we know it, there wasn’t much talk — none, for the most part — of a professional grand slam. There was Bobby Jones’ famous slam in 1930, when he won the four biggest championships available to an amateur: The U.S. and British Opens and Amateurs.

Rae's Creek: The water fronting No. 12 will play a role at Augusta National; its rambling history

LIV it up: LIV Golf doesn't exactly prepare you for Masters week | KEN WILLIS

The British Open began the year Lincoln was elected, the U.S. Open in 1895, and the American PGA in 1916. When the Masters debuted in 1934, as the Augusta National Invitational, it had instant cachet due to Bobby Jones serving as host, but didn’t wear the “major” label until sometime later.

Many of golf’s earliest giants never played a Masters, obviously, and some other multiple-major champs — Walter Hagen and Tommy Armour, notably — were done winning majors and beyond their peak effectiveness by 1934. Hagen was 41 and Armour 37 when the Masters started, and both would win more pro tournaments, but both were well past their very best.

The case for Hagen's additional majors

Might as well take a moment here and, once again, lobby a bit for Hagen. It’s easy to argue Hagen should be credited with 15 majors instead of 11, given his four Western Open wins back when the Western was considered America’s second most important championship behind the U.S. Open.

And, at the risk of country club blasphemy, let’s gently lobby against Sarazen, whose 1935 Augusta win was very splashy (the Sunday double-eagle on 15!) but not necessarily considered a “major” at that early stage of the tournament’s life. His other six majors are asterisk-free, however.

As for the career slam, Rory and Lee Trevino are the two highly decorated contemporary champions missing a Masters win.

Lee Buck’s lack of affection for Augusta was well documented. Some of it was based on social issues of the day, but much of it also had to be about his style of play, which overlapped with Augusta National’s demands in an oil-and-water fashion. The proper path to Butler Cabin isn’t left-to-right on a low trajectory.

Some other greats are missing a piece of the career slam: Sam Snead and Phil Mickelson (U.S. Open); Arnold Palmer, Jordan Spieth and Tom Watson (PGA); Byron Nelson and Raymond Floyd (British Open).

Nelson played in just two British Opens, one near the beginning of his career and the other after he’d retired from full-time play. There’s little doubt Nelson would’ve eventually won a British if he’d made the effort, but in his day, most Americans skipped it because travel cost was more than the potential payoff.

Sam Snead won it in his second try, at age 34, and didn’t play it again until after he turned 50. He was said to be tighter than the bark on a tree, so trading money for a trophy was a non-starter with the Slammer.

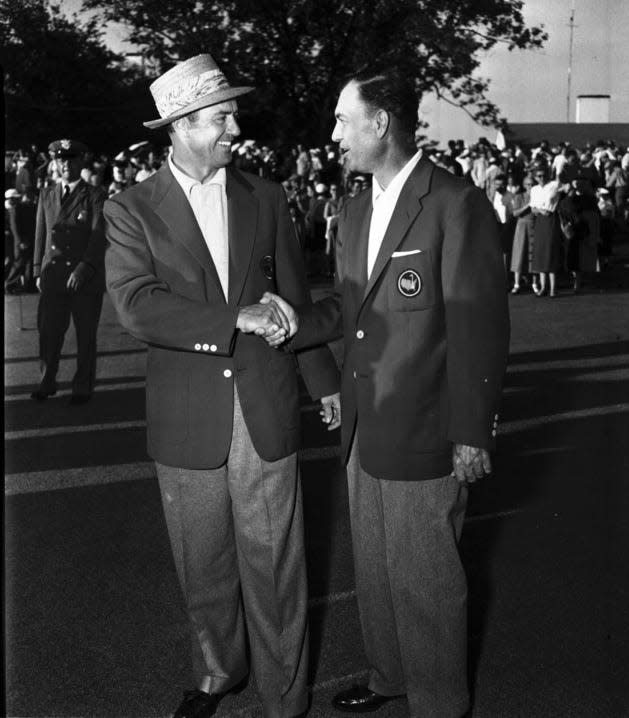

Hogan won the British in his only try, in 1953, the year he also won the Masters and U.S. Open. But he continued to skip the PGA because his damaged legs couldn’t handle several days of 36 holes, which the PGA demanded in those days.

At the ’53 PGA, if a golfer reached the final, he’d have to play 12 rounds over seven days. Still, that summer, Hogan enjoyed a ticker-tape parade in New York to celebrate his “triple crown.”

Arnold Palmer put British Open on our radar for good

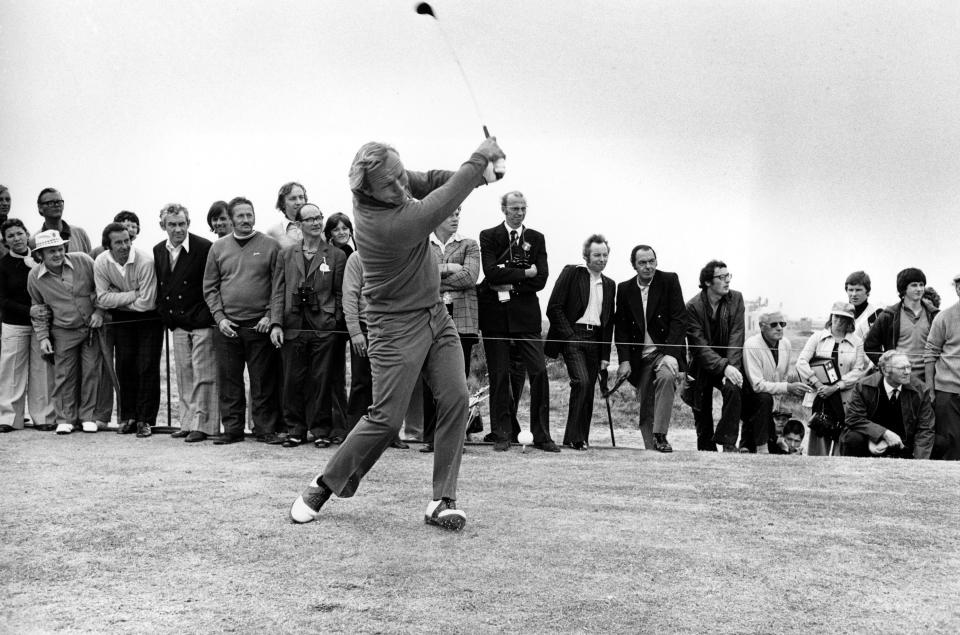

It wasn’t until the early 1960s that the British became a “must” for the top American pros, thanks to Palmer, who drove golf’s bus in a way no one else ever did until Tiger.

After winning the Masters and U.S. Open in 1960, Arnie first mused about a “professional grand slam,” which would include the British Open, which he was entering for the first time that year. He finished second in his first British, a stroke behind Kel Nagle, but returned the next two years and won it, and in turn he put places like St. Andrews, Royal Birkdale and Troon on the proverbial map — for Americans, anyway.

The grand slam Arnie talked about was quickly becoming the Grand Slam as we know it today, and while a natural slam — all four in the same year — remains elusive, Jack took a serious run in ’72 and Tiger won all four in succession from June of 2000 to April of 2001.

Rory McIlroy leaves Augusta this weekend and if he dares look 12 months ahead, he’ll ponder a return to the Masters for his 10th try at completing the career slam since bagging the third leg at the 2014 British Open. The golf public’s attention on his missing piece, along with self-imposed heat, will only grow.

The same, to a slightly lesser degree, with Spieth at the PGA next month and in however many years it takes for him to win it or lose his competitiveness. He’s approaching his eighth attempt at completing his slam with a PGA win.

After wins in three of the four majors, both Player and Nicklaus took just three tries to close the loop. The other three did it on their first try.

Spieth and McIlroy are at a combined 16 tries. They may wish it hadn’t ever become such a big deal. Well, unless they eventually climb that remaining mountain.

Meanwhile, Mickelson will go to the U.S. Open in June for the 10th time after his 2013 British Open gave him wins in three of the majors. He and Snead endured so much heartbreak at that national championship, they should be in a Hank Williams song.

A pleasant sidelight to the focus on the three current slam chasers is all the retroactive attention given to the five golfers in that exclusive club.

The “five with all four” probably enjoyed their historic journeys more than today’s three pursuers.

Jack and Tiger, in fact, enjoyed collecting the slam so much, they did it three times each.

— Reach Ken Willis at ken.willis@news-jrnl.com

This article originally appeared on The Daytona Beach News-Journal: Rory McIlroy misses Masters cut; won't join Tiger Woods, Jack Nicklaus