Gratitude and thankfulness: Local teacher shares story of adopting student

CENTREVILLE – The sequence of events that led a cheerful, 7-year-old girl to Carmita Hunter’s second-grade classroom at Centreville Elementary could fairly be considered odds-defying.

For starters, the new student had experienced trauma from a young age, eventually being removed with four siblings from her Battle Creek home and into a foster-care situation. By chance, her placement was with a family living in Centreville.

Next, it was fall of 2020 and COVID-related precautions were still in full force. So much so, her foster mom opted to have her begin the school year taking courses through Centreville’s online instruction.

Eventually, however, foster mom Tina Wagler concluded that returning to in-person learning would be best for young Mari. By sheer fate, she was assigned to Hunter, one of three second-grade teachers in the elementary school.

A variety of factors are taken into consideration when school personnel decide classroom placement of a new student. At the time she was assigned to Hunter’s room, there was no way for anyone involved to realize the wheels of destiny for Mari were set in motion.

Meanwhile, Hunter and her husband, Mike, were unaware they were on the fringe of a 20-month roller coaster ride that would prove to be equally lifechanging.

“It was within the first month of the school year, she showed up, she was sweet, she was quiet and then I remembered her from when she was here in kindergarten,” Hunter said. “The child who came into my classroom that day was not the child I remembered from when she was in kindergarten.”

Hunter said Mari was in kindergarten when she was removed from her Battle Creek home and placed in Wagler’s care. Mari, whose classroom was just down the hall from Hunter’s, was on strong medication, and attempting the long and difficult process of recovering from trauma, Hunter said.

Hunter’s memory of 5-year-old Mari is heartbreaking.

“She was a kindergartner who would scream and run through the hallways to find her foster sister … it was that fight, flight, freeze mentality and Mari needed the security of her foster sister because Mari’s biggest fear was abandonment,” Hunter said. “I can’t really blame her. But I remember she was out of control, kicking, screaming and if you had told me that year that this little girl running all over the hallways is someone I would one day adopt, I’m pretty sure I’d think you were crazy.”

Second-grade Mari, Hunter said, was a far different young lady than kindergarten Mari. Hunter saw a student who was sweet, worked hard and had potential for many good things and by mid-October, a once-unfathomable thought entered Hunter’s mind. Of all things, it was triggered by parent-teacher conferences.

Hunter said she contacted Wagler to inquire about whether anyone would be attending Mari’s conference.

The query led to a lengthy response from Wagler, and it involved the full backstory about Mari and the distressing account of a girl whose first five years of life were anything but conventional.

Mari was the second of three children from the same mom and dad. Dad, however, was incarcerated not long after the third child was born. Mom, meanwhile, would go on to have two more children.

The oldest of the five was adopted by his maternal grandmother, the younger brother has special needs and was adopted out of foster care. Meanwhile, the two half-brothers were adopted by their dad’s parents.

Hunter said it appeared Mari’s shot at a new start in life was passing with every opportunity.

“I left parent-teacher conferences that night knowing parental rights had been terminated, I knew Mari’s four siblings were all adopted, I knew an aunt was going to consider adopting Mari but wound up backing out,” Hunter said. “When I got the story, all these people who had access and weren’t taking advantage of that access, it just broke my heart.”

At the time, Carson Hunter, the third of the Hunters’ three children, was a high school senior. The older two – Madison and Ross – were out of the house and starting lives of their own.

Hunter said a phase of life she and Mike welcomed and dreaded in equal parts was on the horizon with Carson’s impending graduation.

“We live right here in town, our house was the place where everybody always came and hung out,” she said. “So, it went from everybody being there after the football games, after basketball games, to being a very, very quiet place. Our schedule went from every night being somewhere and super busy, to not having to be anywhere. It was lonely, quite honestly.”

Further evidence of circumstances aligning perfectly.

The night of conferences, Hunter went home, sat her husband down and delicately brought up Mari, her plight – and a far-flung, shot-in-the-dark idea of adopting Mari. Mike took a long and practical look at the situation.

“I was never against it … Carmita was gung-ho,” he said. “I never said no but I was like, ‘Think about what this is going to mean for us because it’s going to change many, many things. We’ll be going back to sitting in the stands, going to practices, all kinds of stuff that we had just finished doing.”

Nonetheless, the next step was taken Thanksgiving weekend, three years ago this week, when all three of their children were home.

Hunter, currently in her 22nd year as a teacher, said her concerns included whether any of the kids would take in Mari if something were to happen to her and Mike. The conversation was brief and the matter was decided, essentially, while the holiday dinner was still warm on the table.

The Hunters, married since June 1993, worked with Mari’s caseworker and started the process of a one-year fostering requirement. Mari moved in in May 2021.

Hunter said she and her husband felt an instant sense of fulfillment knowing Mari was now under their roof.

“Our job was to replace trauma with happy memories,” she said. “It’s amazing when you see that transformation just by doing everyday things. Just by giving a child routine, consistency and a life that would generally be considered normal.”

The adoption was final April 15, 2022, less than a week before Easter. Unfortunately for the Hunters, COVID restrictions still in place prevented the family from meeting in Probate Court and celebrating Judge David Tomlinson signing documents making the adoption official.

Still, the phone call from Probate Court confirmed the good news and a certified letter arrived a few days later, further cementing the procedure.

The days of neglect, and of mental and physical abuse, were situations Mari would never again experience. A scar on her cheek serves as a reminder of Mari’s previous life. She is now living her best life, Hunter said.

A Constantine native, Hunter holds no ill-will toward Mari’s birth mom, who gave birth to her first child at 17, Mari at 18 and three more boys within five years.

“She was just too young, very young … a young mom with too many kids, no resources and an incarcerated husband/partner,” Hunter said. “I don’t fault her in any way … she just didn’t know what she was doing as a mom. I don’t doubt she loved her children, she just had too many too fast.”

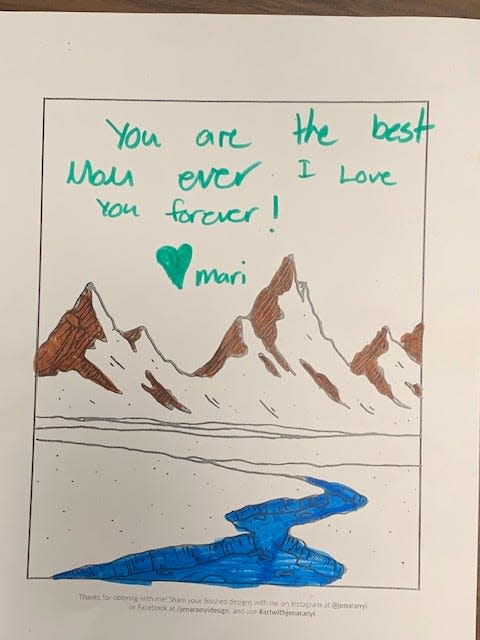

The Hunters this week will enjoy their second Thanksgiving as a family of six. Hunter acknowledged the role fate played in bringing her and Mari together.

She said with certainty she and Mike would not have adopted Mari had Mari been placed in another classroom. Primarily, Hunter noted, there would not have been the occasion to meet with Wagler over parent-teacher conferences, typically an innocuous event that proved to be monumental for the Hunters.

“Mike and I aren’t out looking for accolades for what we did,” Hunter said. “We’re just happy to share our story as an example of gratitude and thankfulness, and to highlight all the people who make adoption work. From the moment Mari was taken from her home, there were people who started that healing process – social workers, therapists, CASA workers and many others.”

“Ultimately, we just want Mari to be healthy, happy and make good choices,” she added. “And if we had any influence in any of those things, then it will have been worth it.”

This article originally appeared on Sturgis Journal: Centreville teacher adopts student