The graying of America's prisons: 'When is enough enough?'

One of Wayne Pray's earliest run-ins with the criminal justice system occurred when he was 22. He was arrested for having pills in two envelopes. At 29, he was given probation on fraud charges.

By the time he was 41 he was charged as a drug kingpin, according to court documents and a New Jersey report that detailed black organized crime in the state. In 1990, a federal judge sentenced Pray to life in prison without parole, plus three 25-year stints for, among other things, cocaine and marijuana possession and distribution.

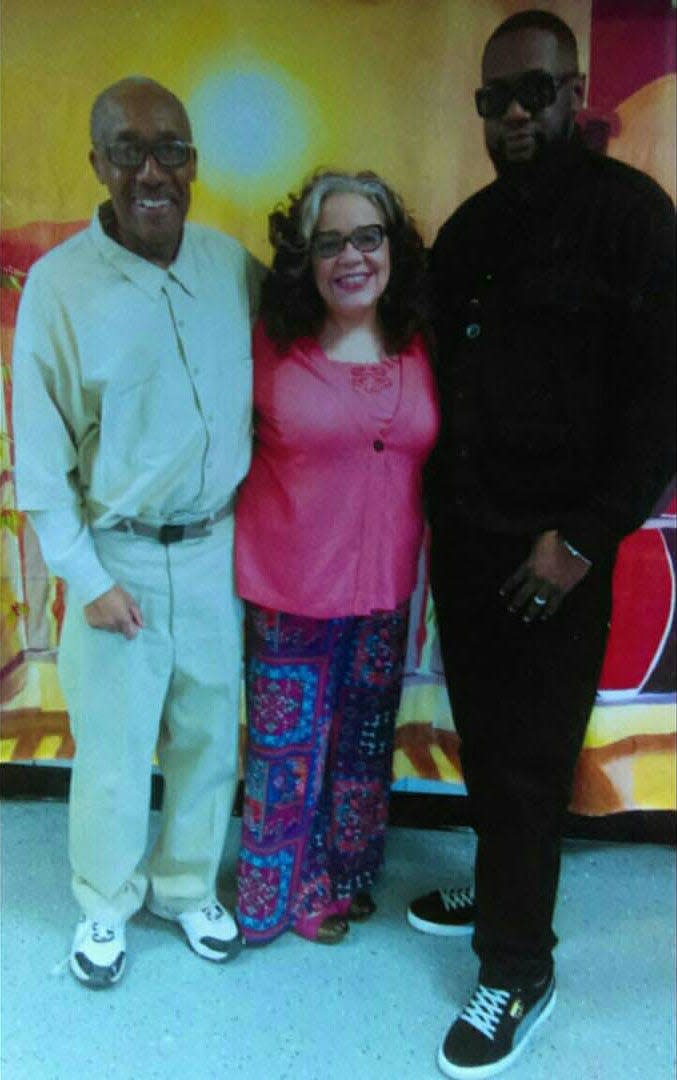

Now 71, Pray has been locked up for three decades on nonviolent offenses, most recently at the federal prison in Otisville, New York. He is one of about 20,000 older federal inmates — prisoners over 55 who are among the fastest growing population in the federal system. Many of them were given life amid the war on drugs of the 1990s.

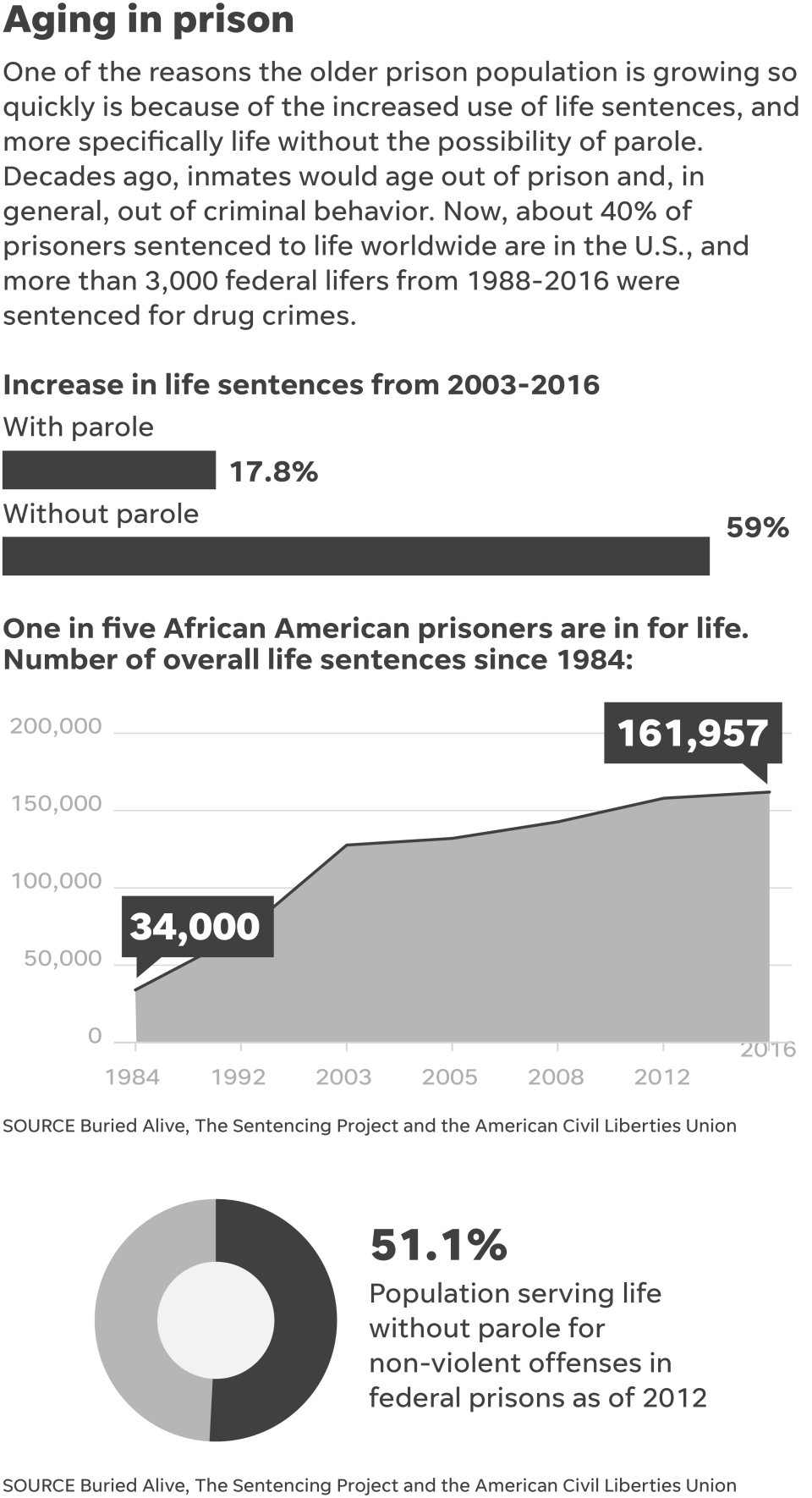

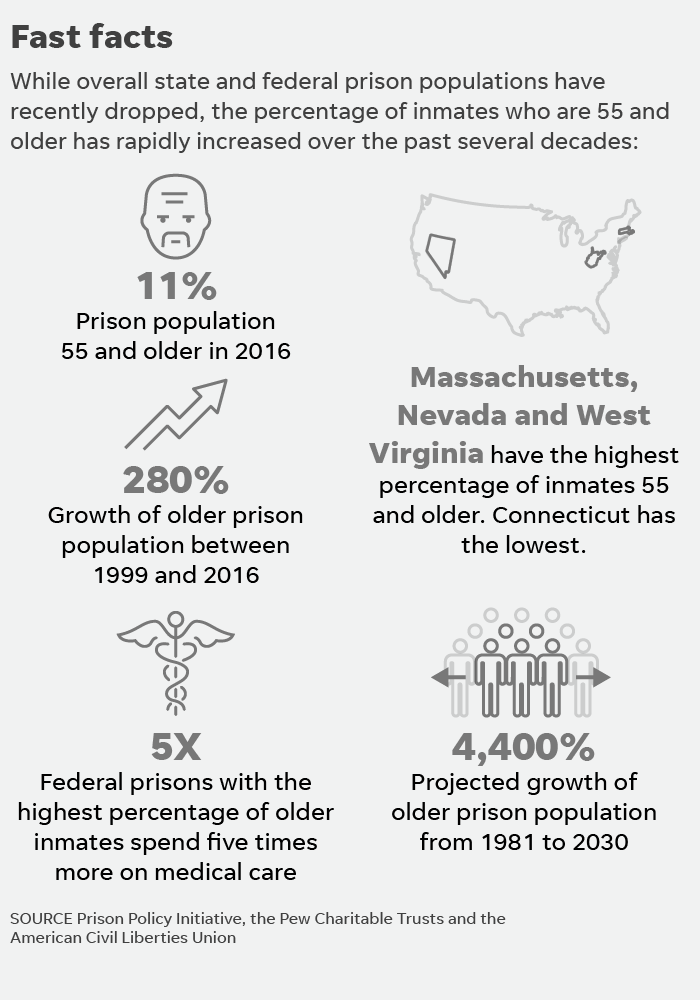

Mandatory life sentences mean a federal prison population that is graying in large numbers. This group puts the greatest financial burden on U.S. prisons, while posing the lowest threat to American society.

Pray's status, and that of others aging in the system, presents tough questions: How old is too old to remain incarcerated? Is Pray, at 71, the same threat he was at 41? And if he isn't, then why is he still behind bars?

A telephone interview with Wayne Pray, also known as Akbar Pray, quickly reveals that his life, like many of ours, is multifaceted. Today he's a poet and a voracious reader. He's considered a model citizen in prison. He mentors kids who are on the cusp of making the same mistakes he did and created a CD with important life lessons called "Akbar Pray Speaks to the Streets."

A letter from Newark Mayor Ras Baraka (written in 2012, when Baraka was still a high school principal) describes Pray as a man who has encouraged students to be "critical thinkers responsible and accountable to their families, and communities." Baraka is one of many people who have spoken up in support of Pray's pleas for clemency, all of which have been denied.

Lack of judicial discretion

From 1993 to 1996, nearly 800 drug offenders were sentenced to life without parole in federal prison, according to the Buried Alive Project, which tracks rates by year and state. That's 57% higher than during the previous four-year period.

Prosecutors wield a lot of power when it comes to sentencing. It isn't uncommon for attorneys to push plea deals on defendants in exchange for information. And the rejection of those deals sometimes means elevated charges that result in mandatory minimum federal sentences, including life.

That lack of judicial discretion was enough to push Kevin Sharp off the bench. He was a federal judge for six years in Nashville and was forced to hand down three life sentences, all of which he disagreed with. One was for Chris Young, a 26-year-old who faced drug charges and rejected a plea deal because he wanted his day in court. The other two were for Young's co-defendants.

"The biggest responsibility you've got as a federal judge is sentencing people, taking away someone's liberty," Sharp explains during a phone interview.

Giving prosecutors the ability to manipulate sentencing is a "recipe for abuses" and eliminates the judge's ability to act as a neutral third party who hands down sentences that are fair, that keep in mind the defendant's personal and criminal history, and that weigh socio-economic factors that may lead to criminal activity. Mandatory minimums, Sharp says, "encourage (prosecutors) to overcharge people either because they are trying to extract some kind of cooperation from them or it's just vindictive."

The only thing that will reduce that power, he adds, is if the federal government steps in to change certain rules behind sentencing.

While the First Step Act, passed by Congress last year, changes mandatory minimums for some federal offenders, not all will be helped by it, including inmates such as Pray who were convicted in cases involving powder cocaine instead of crack.

Federal prisons that house larger populations of older inmates spend more on medical costs. And in many cases, the higher price tag comes with substandard care.

Wayne Pray's criminal history

The inmate's request for clemency includes a look at his criminal record, which goes back to 1971, and letters written on his behalf that detail how much he's changed since he was first incarcerated 30 years ago.

Pray reports a slew of physical ailments that include arthritis and high blood pressure. He says his mental health is also something he works hard to maintain every day.

When he talks about keeping his spirits up, Pray sounds hopeful. When talking about some aspects of his past, he seems more detached.

But as troubling as Pray's past is, Judge Claude Coleman — a former director of the Newark Police Department — says the justice system gains nothing by continuing to lock him up. Coleman, who was instrumental in dismantling Pray's drug operation, says Pray was a nonviolent offender who would have a hard time running a similar crime syndicate (that at one point reportedly involved 300 people and made millions of dollars) if he were released today.

"I was satisfied with having dismantled his organization," Coleman said during a recent interview. "We relieved him of all of his assets. (Incarceration) should be about reform. Now it's strictly for punishment. But to punish you for the rest of your life?"

From the streets of Newark to Otisville

A series of beeps cuts my phone interview with Pray short. He can only talk in 15-minute intervals.

From a recording studio of USA TODAY's office in McLean, Virginia, I wait the mandatory 30 minutes for him to call me back. This is our second attempt at an in-depth conversation.

When he returns, he continues to talk about the childhood that he says led him to crime.

Clemency denied

Pray's requests for clemency have been denied, most recently last year.

According to Pray, his family was full of drug dealers and addicts. Some of his earliest memories are of his parents hiding drugs in his pajamas. If the cops came to search the home for illegal substances, they wouldn't look there. If a customer showed up, his parents would wake him so they could retrieve and sell the product.

Pray says his brother started selling drugs at age 14 and was dead by 31.

Court documents show that Pray was dealing by the time he was in his late 20s. He used drug money to open up other businesses, according to Coleman. Pray says at one point he owned two used car dealerships and was a fight promoter.

"The lifestyle itself becomes addictive," Pray says.

The charges that led to his life sentence involved more than 250 kilograms (550 pounds) of cocaine and about 200 pounds of pot. He maintains that the "kingpin" charge was trumped up, the result of a rejected plea deal. Prosecutors wanted information about other people, including politicians, that Pray says he refused to give.

Personal tragedies from prison

Prison is a place where even the hardest criminals get emotional when they think a lifer is getting out, according to Pray. For a moment, Pray wrote in a letter from prison, he thought his fate had changed, but his hopes were dashed at that time.

A denial of Pray's request for clemency exemplifies the complicated nature of his case. It stated that Pray had been "one of New Jersey's most notorious drug traffickers — responsible for a decade’s worth of human suffering" but also that he had made "significant effort" toward bettering himself while incarcerated.

The septuagenarian has 18 children, and he says he has a good relationship with nearly all of them. Some visit on Father's Day.

Three of his children have died since he has been in prison — he lost two sons to HIV and one to violence, he says. He mourned each death behind bars and spoke to one son by phone before he died.

Pray has applied for clemency twice to no avail. Yet he still holds out hope that he'll be able to spend his final days with his family. In a letter that was part of his clemency plea, he called it his "near prayer."

"I'm not trying to justify what I did. But let the punishment fit the crime," Pray said during our phone interview. "When is enough enough?"

This is the first installment in a series about prisoners serving life sentences for non-violent crimes. This series is being published in conjunction with the Buried Alive Project, which is working on a video-driven Letters From Lifers campaign.

Eileen Rivers is the digital content editor for USA TODAY's Editorial Page and the editor of the newspaper's online vertical Policing the USA. Reach her on Twitter @msdc14.

Tell us your story

Are you incarcerated for life for non-violent offenses? Do you have a loved one who is? Do you have views on the justice system and incarceration for non-violent drug offenses that you'd like to share? Tell us your story. Share your views. Call 540-739-2928 and leave your story or email letters@usatoday.com. We'll pull some comments and publish them on our site.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Federal prisons in the US have a problem with older inmates