Great mystery of Saturn’s Rings May Have Been Solved: New Study

You know the old joke about the planet Saturn, right? God liked it so much he put a ring on it.

Or, as is more accurate, a lot of rings (seven, according to NASA). But just how those rings got there is a mystery that's had scientists scratching their heads for centuries.

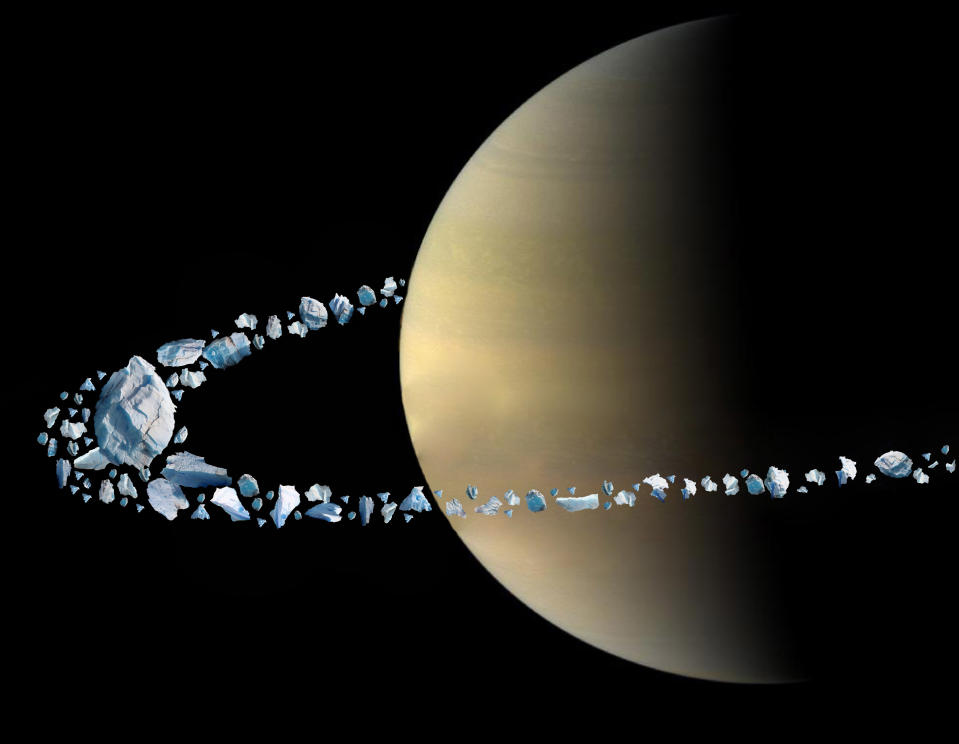

That may be changing, though. A new study published in the journal Science on Thursday suggests that a hypothetical moon (called Chrysalis by the report) came too close to Saturn's gravitational pull and was torn apart. What looks like solid rings from afar are actually tiny bits whirling at incredible speeds.

The rings are now thought to be between 200-100 million years old and are made up of rubble from that moon which, over the millennia, has become shaped and flattened as it whirls. They're about 30 feet thick in certain places but cover 170,000 miles in diameter.

But it helps to know a bit about Saturn to see how a moon might break up in its gravitational pull. Saturn has 82 moons (some of which are still unofficial), including the large Titan, and each moon has its own gravitational force. If Chrysalis got too close to the planet's surface (or another moon's), and passed what's called the Roche limit, it would be pulled apart by those gravitational forces.

Saturn's surface isn't solid (it's mostly made up of hydrogen and helium, so no one could walk on its surface). UniverseToday explains that it is more massive than Earth, but it has a very low density, so the "surface" is only 91% of Earth's gravity. (If you weighed 220 pounds on earth, you'd only weigh 202 on Saturn's "surface.")

Originally, scientists believed Saturn's rings were over 4 billion years old, when the planet was reasonably young and had a strong gravitational field that could capture asteroids or comets to create its rings. But thanks to NASA missions in the 1980s and, more recently, Cassini's 2004-17 reports, experts believe the rocks in the rings are much younger.

"If they’re not old, they must be a result of a breakup of a body, like a large comet or a moon later on," Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor of planetary science Jack Wisdom, Ph.D., and lead author of the new findings told The Wall Street Journal.

Additionally, the destruction of Chrysalis may explain Saturn's tilt, according to the scientists. All of the planets except Mercury have some tilt, but the loss of a large moon could have exacerbated (or even reduced) the degree to which Saturn tilts.

Francis Nimmo, professor of planetary science at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and a co-author of the study, told the Journal: "It ties together two puzzles that had previously been treated as separate. It turns out that you can explain both in a single story."

Co-author Burkhard Militzer, a professor of planetary science at the University of California, Berkeley, noted that Saturn's rings are slowly eroding. "So next time, when you look at Saturn’s rings, we recommend you appreciate them a little more because (they) will not be there forever," he wrote on his website.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com