The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is so large that tiny creatures are making it home

The so-called “Great Pacific Garbage Patch” has now become so vast and permanent that a diverse range of species have taken up residence within it, according to new findings.

Every year between 1.15 to 2.41 million tonnes of plastic are entering the ocean – at the rate of one garbage truck every minute.

Some 79,000 tons of that plastic debris, the weight of 500 jumbo jets, is swirling in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre between California and Hawaii, one of the most polluted marine areas in the world.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) is not island-like but rather millions of pieces of detritus covering a surface area twice the size of Texas, according to conservation non-profit The Ocean Clean-Up.

It’s partly made up of microplastics – tiny pieces that can’t be seen by the naked eye but are easily ingested by marine life and end up in the food chain.

Now, a study, published on Monday in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, has revealed that dozens of tiny coastal species are surviving and reproducing in the GPGP.

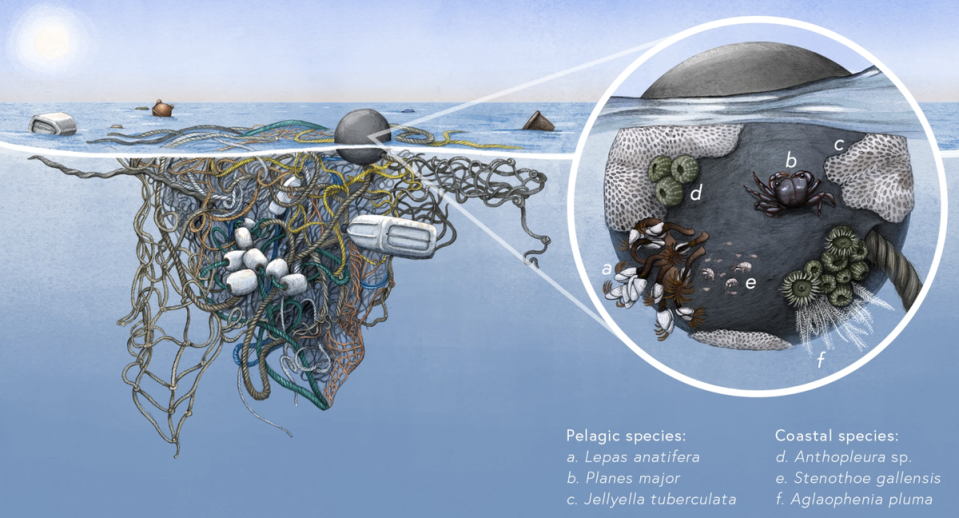

Among the colonies are crabs, sea anemones and miniscule invertebrates.

Unlike organic matter, plastic, particularly sturdy items like buoys and nets, don’t decompose and float around in the ocean indefinitely, acting as life rafts for tiny creatures.

Researchers analysed rafting plastic debris from the eastern part of the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. More than 100 items of debris were studied after being pulled out of the garbage patch between November 2018 and January 2019.

Some 484 marine invertebrate organisms were discovered from 46 different species. Eight in 10 of these species are typically found in habitats thousands of miles away.

“The issues of plastic go beyond just ingestion and entanglement,” said Linsey Haram, lead author of the article and former postdoctoral fellow at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC).

“It’s creating opportunities for coastal species’ biogeography to greatly expand beyond what we previously thought was possible.”

The study warns that by coastal species’ new plastic homes in the ocean are “fundamentally altering the oceanic communities and ecosystem processes in this environment with potential implications for shifts in species dispersal and biogeography” on a large scale.

It will take an estimated $175bn each year to protect the global ocean, according to the World Economic Forum. Netween 2015 and 2019 less than $10bn total was invested in the cause.