As Buffalo shooting victims testify in Congress, race and history circle us

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On a Saturday afternoon in May, History stared at me in an art gallery in New York City.

We circled each other. His ferocious eyes warned me of news that I didn't know awaited me outside once I turned my phone back on. Her piercing eyes warned me she knew my secret shame.

My husband and I were looking for another art exhibit when we wandered into the Marian Goodman Gallery. Four people already were waiting for the free showing that was about to start at 2 p.m.

A showing of what? The guide was vague but assured us we wouldn't regret spending 40 minutes to go through "The Awakening" by Tavares Strachan.

A Black man steps out of history

Bob and I, amateur art lovers, had never heard of the gallery or the artist, but we're always up for unscheduled discoveries. Happily we showed our COVID-19 vaccination cards, put on masks, and agreed to turn off our phones and not use them during the show.

The guide took our group up an elevator to the fourth floor, and when the door opened, a Black man dressed in a beige fedora and an off-white linen suit was sitting outside a room. He bowed his head.

Opinions in your inbox: Get exclusive access to our columnists and the best of our columns every day

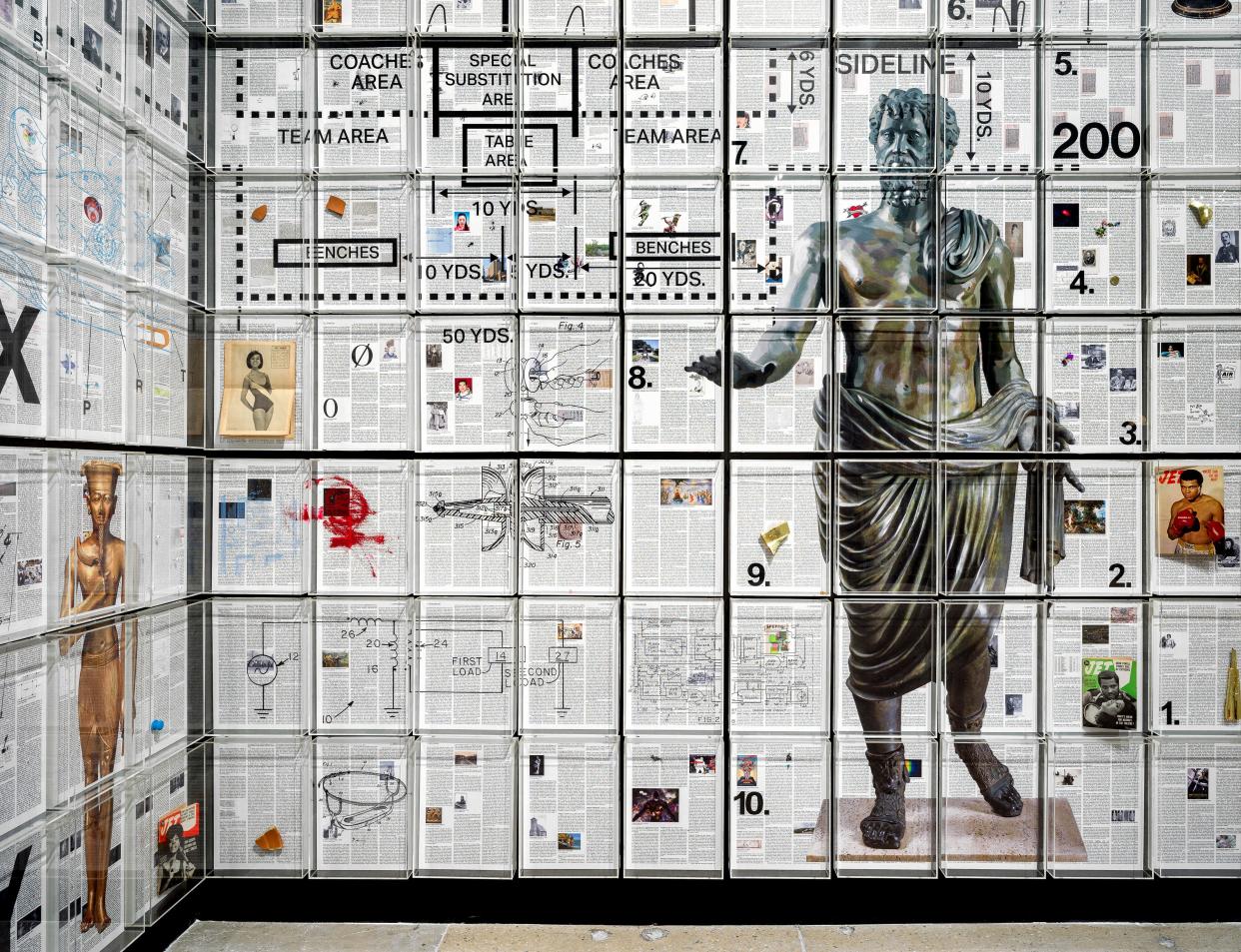

Inside the room, the walls were covered with what looked like newspaper pages. They actually were pages from "Encyclopedia of Invisibility," the artist's 10-year research project to make his own encyclopedia featuring people, places and things left out of most mainstream history books.

Bob and I, with four masked strangers, were trying to read the walls and absorb the images accompanying the words, when the Black man sauntered in. Hands in his pockets, he stared at the pages, too, and slowly stared at each of us. He was unmasked. Then he began humming.

We masked strangers glanced questioningly at each other. I looked back at the Black man and realized that he was wearing tap dancing shoes, and that the face and body belonged to a woman.

It was in that moment the exhibition became both public and private. I cannot go into detail as that would give away the experience for you. But we strangers were now in that space we know exist yet struggle to share. What I can say is that it involved the "Encyclopedia of Invisibility" opening up in a physical manner.

In the center of the room sat the large tome. The walls were covered in a gridwork of pages from Strachan's encyclopedia, each entry highlighting aspects of history that have escaped society's larger narrative.

Then, without warning, we were transported to a courtroom where a trial was in session. In this shift I was left to think about racial space – cultural areas where some people are safe and others are not. Strachan presents the exhibition as an experience where the weight of the hidden, the marginalized, the invisible become very personal.

There was more, but you have to see for yourself.

In the last room, Black History in the fedora wandered among us masked strangers humming, singing, staring. When it was my turn, I stared back, trying hard to understand. The tap shoes kept moving, so I followed, and we circled each other a few rounds before Black History let go of me and left.

A white man who hunted a Black neighborhood

Bob and I exited "The Awakening" dazed and amazed on that May 14. Later, we learned that while we were in the exhibit, a white 18-year-old had driven 200 miles to Buffalo, New York, parked about 2:30 p.m. and shot 13 grocery store shoppers, killing 10 Black people.

According to documents, police accounts and personal writings from the suspect, he drove the long distance to the grocery store he selected because he knew it served a predominately Black neighborhood and would be crowded on a Saturday afternoon. The documents spell out that the author was obsessed with the "great replacement theory," which claims that the changing racial makeup of America is not a natural or organic process but an organized effort by a powerful and shadowy group.

Why do young whites kill out of hate?: Schools aren't teaching racist past

Since May 14, I've been haunted by those ferocious eyes that followed us in the art gallery, and I've understood the warning: History's not history.

And I've cringed: The piercing eyes had reminded me of something in my own history.

What I as a child 'knew' of racism

Sixth grade in Phoenix, a couple of years after my Vietnamese family had escaped the fall of Saigon in 1975 and the Mount of Olives Lutheran Church had sponsored us out of a refugee camp. My English was good enough by then that once a week I attended an advanced class with seventh- and eighth-grade students. Fewer than 10 of us were in this class, which the teacher conducted as more of a chat among friends.

That day's topic was racism, and I was on such a high horse about how I was not a racist.

The teacher, a white man, asked me that if I had to grade the different races, who'd get A, B, C and D?

Me: Whites, Asians, Hispanics and African Americans.

Teacher: So you're not a racist, huh?

Even me, as a racist child against myself and my fellow Asians, didn't think to include Native Americans in that bigoted (de)grading system, although my school in Arizona's capital had plenty of Indian kids. What did I know?

Well, whatever my history books and my culture taught me – apparently the Declaration of Independence's "all men are created equal" but not the reality of race in America, past and present.

Aside from slavery, the Civil War and the civil rights movement, what do you know of our racial history? What have you been taught? What have you agreed to learn?

Do you know what happened a century ago this week in Tulsa, Oklahoma? A lot of Americans didn't until they watched HBO's 2019 "Watchmen" series. From May 31 through June 1, 1921, a white mob massacred "Black Wall Street" because it was one of the wealthiest African American communities in the country. Up to 300 Black people were slaughtered.

'Fight to the finish': Tulsa Race Massacre survivor on lawsuit and struggle

I knew of it before seeing "Watchmen," but only because I'm a journalist who had edited pieces about the Tulsa massacre. Common comments of shock among my friends of all races were: "We saw the first episode and looked at each other like, wait, did they make that up?" "We had to Google Tulsa massacre to learn if it was real." "Why didn't we learn this in school?"

The Tulsa Race Massacre is just one historical moment of violence and discrimination that Americans are only recently learning. It's not Black history. It's not Asian American and Pacific Islander history. USA TODAY has a whole series called “Never Been Told: The Lost History of America’s People of Color.” All of these stories are America's history.

We have designated months for Black history, AAPI heritage, Pride and more to not only celebrate previously unknown achievements that individuals have contributed to the greatness of the United States, but also to acknowledge the lessons America must recall and recognize to live up to the preamble to our Constitution: "Form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity."

What I want my posterity to know

My Vietnamese family became U.S. citizens in 1982. I married Bob Elston in 1995, and we now have four children, ages 24 to 15. We've been pleasantly surprised at what they've learned of history in their schools outside Washington, D.C. The high school history book even had substantial information about the Sister Queens who ruled Vietnam about AD 40 – and their influence on women's position in my motherland.

More from Thuan Le Elston: The moment I pledged allegiance

I want my children and all my descendants to be good Americans – not just patriots, but also who help keep America's promise of equality and democracy and who help make America what it must be. This means each has to learn the best and the worst of U.S. history.

The United States I believe in and love doesn't drive 200 miles to hunt down Black Americans. On June 1, a grand jury indicted the suspect in the Buffalo mass shooting on additional charges of domestic terrorism motivated by hate and 10 counts of first-degree murder. A week later, family members of the Buffalo victims are testifying on Capitol Hill.

Live updates from congressional hearings: ‘I don't want it to happen again'

Don't forget Buffalo tragedy: In our silence, racism thrives

The United States I believe in and love does include conceptual artist Tavares Strachan, a Bahamian-born American who has traveled to the North Pole and trained as a cosmonaut in order to explore the borders of science and mythology so that his art can break and make history.

When he heard about the Buffalo tragedy, Strachan told me, "I felt deep pain. ... The great replacement theory, which is a newer, more updated fear/hate-based philosophy, cannot stop humanity’s quest for equal rights and justice for all."

Thuan Le Elston, a member of USA TODAY's Editorial Board, is the author of "Rendezvous at the Altar: From Vietnam to Virginia." Follow her on Twitter: @thuanelston

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Buffalo shooting victims testify in Congress: Racism, history repeat