The greatest generations? Remembering two famed Savannah surgeons and one's role in D-Day

In November 1942, Loyd Osteen, a native of Pembroke, graduated from Georgia Medical College specializing in anesthesiology. He soon enlisted in the Army and spent the rest of World War II in frontline field hospitals, usually located very near enemy lines.

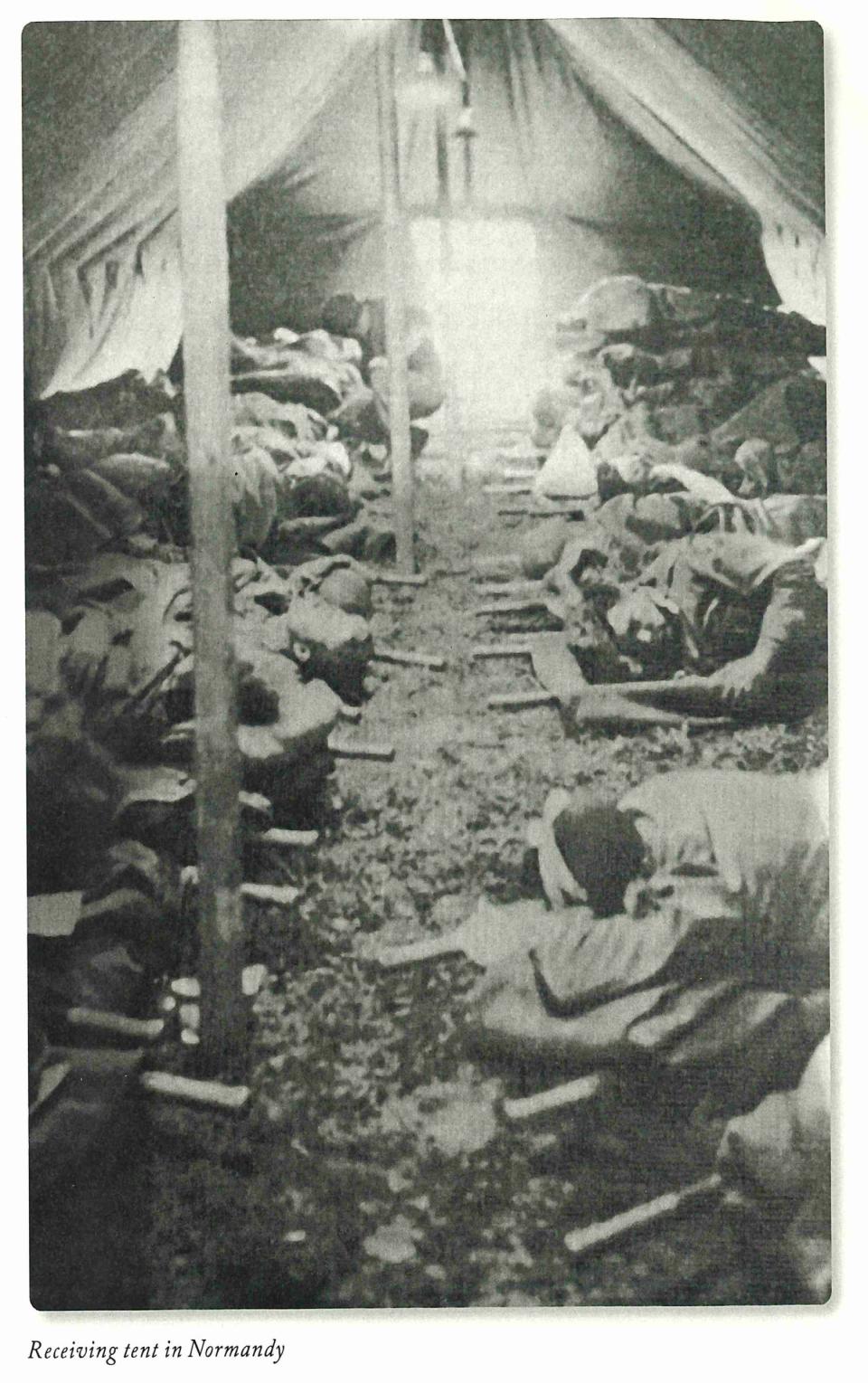

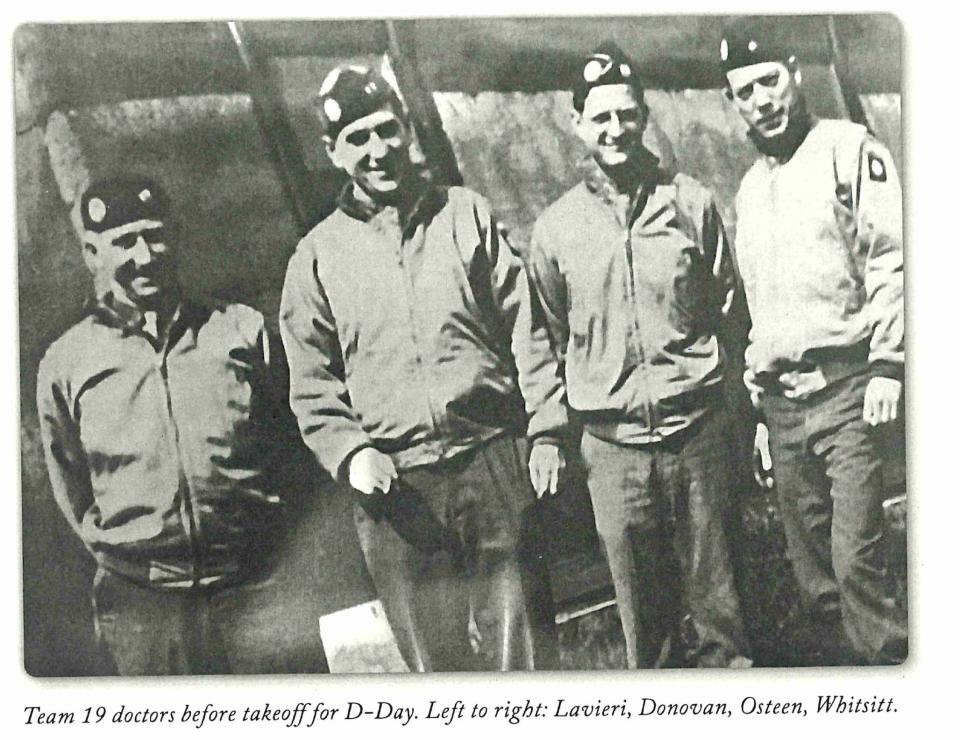

Those hospitals treated the most severely wounded and the mortality rate sometimes exceeded 25%. He participated in the North Africa campaign, the landing at Palermo, and to England to train for the landing at Normandy. His surgical team was assigned to the 82nd at Airborne Division whose men had parachuted into the area behind Utah Beach before the actual landing began.

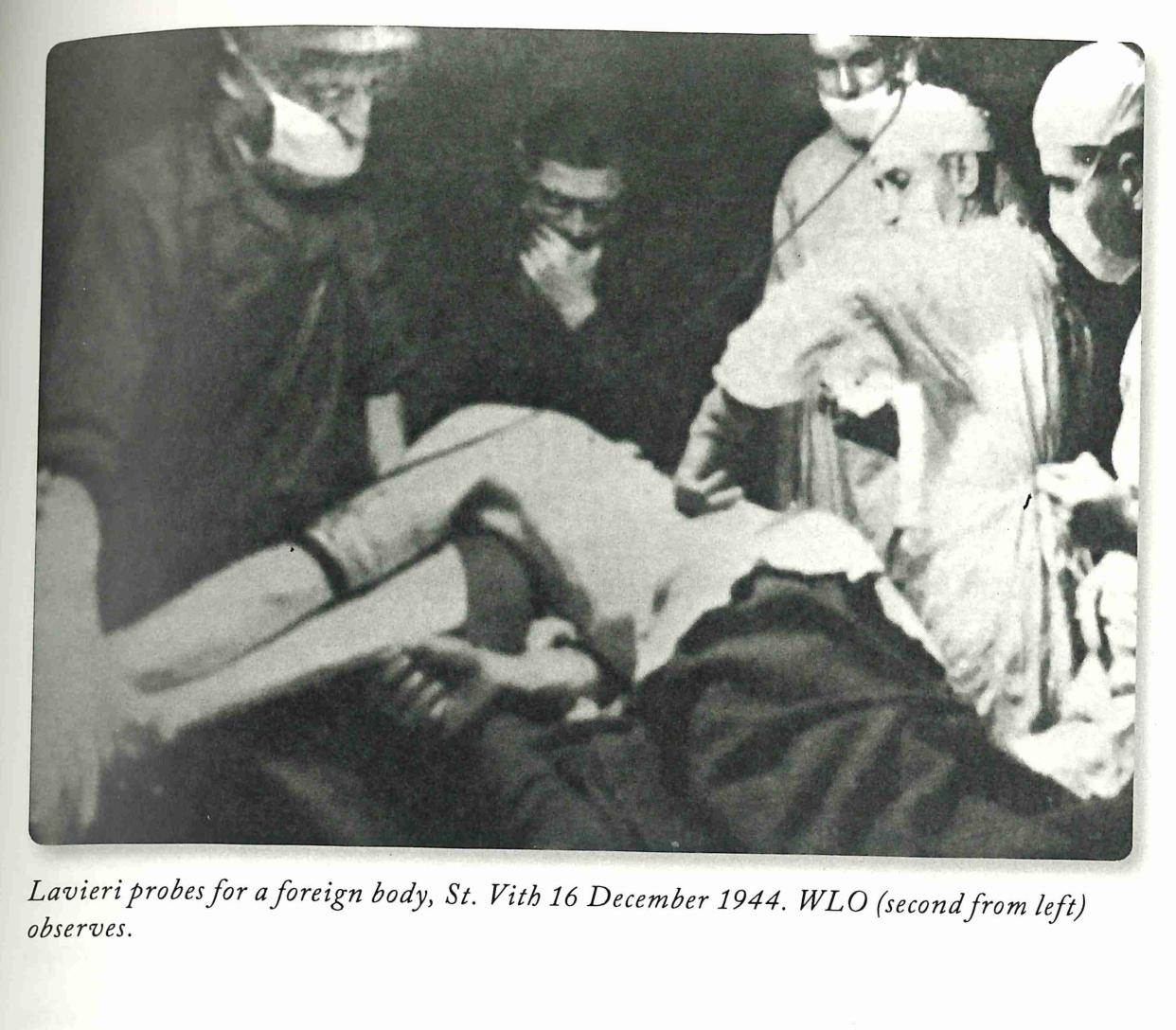

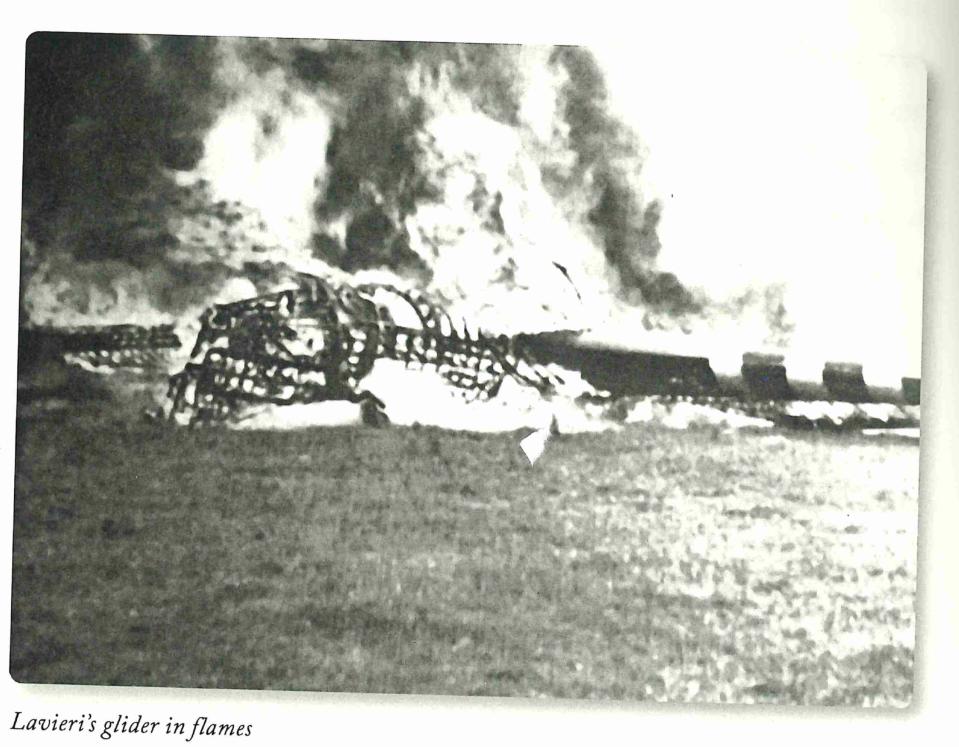

At dusk on D-Day. the support personnel, including Dr. Osteen, came in gliders, landing within a short distance from Utah Beach. His team set up the first field hospital and over the next four weeks worked 19 to 20 hours per day. In August his team joined the Third Army and remained with them in battlefield hospitals for the remainder of the war including many major battles such as Cherbourg, the Battle of the Hedgerows, Aachen and the Battle of the Bulge. His last duty was to assist in relieving the horrific suffering at Buchenwald concentration camp where he and his team occupied the barracks vacated by the Nazi SS troops.

More: World War II forces sweetheart singer Vera Lynn dies at 103

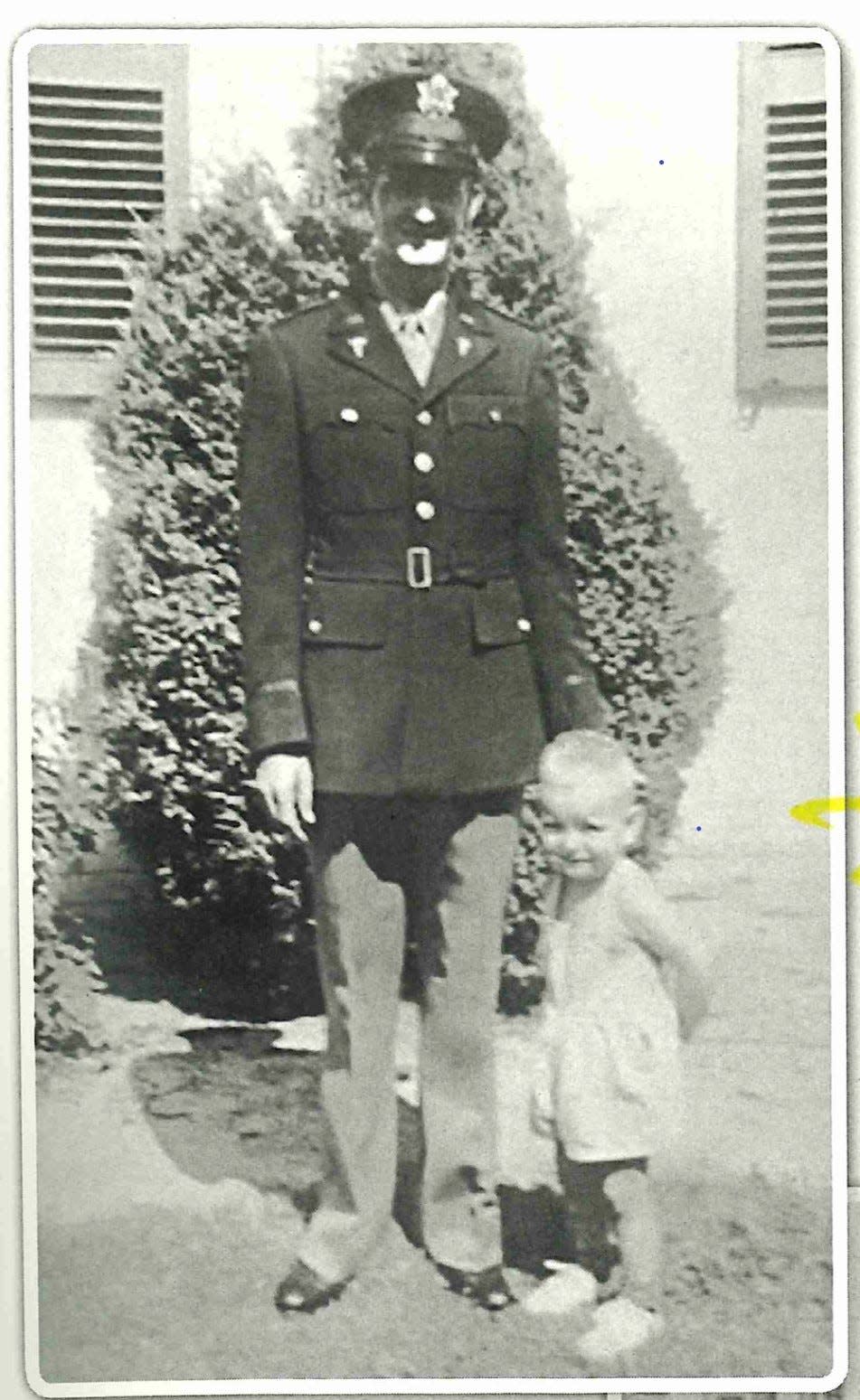

Upon his discharge in July 1945, Loyd returned to Savanah to his wife Elaine, and their son, Bob, whom was born in 1941. Loyd opened the first anesthesiology practice in Savannah and, as teenager, Bob would accompany Loyd to the operating rooms at the old St. Joseph’s and Candler hospitals where Bob would scrub for his dad and operate the breathing apparatus for the patients.

Bob graduated first in his class at Savanah High in 1958 and, in his father’s footsteps, became a surgeon at the Brigham and Womens, one of the two Harvard Medical School teaching hospitals. Bob retired at the top of his profession repeatedly earning teaching awards at the Medical School, including ones named for him. Bob died last year but just before his death he wrote “Surgery Under Fire” about the tremendous strides made during WWII for the treatment of massive and traumatic wounds.

More: A tribute to the great American soldier

It included these excerpts from the 292 letters Loyd had sent home:

How soldiers look at death

“As I look at each boy to decide what to do, I remember that he has a sweetheart or wife or mother at home who feels about him just as mine do and who probably are praying that his doctor is the best and will do his best. A walking wounded came and just happened to glance at a boy lying severely wounded on a stretcher by him and recognized his brother whom he had not seen in almost a year. Don’t misunderstand that it’s all bad or sad for the joy is in seeing so many that could be cured and in seeing how much they are relieved by and how much they appreciate medical care. Though some of my cases are most difficult, it’s astounding to see the differences in the way these fellows and the people in civilian life approach going to sleep. You remember at home the problem was to reassure and try to quiet their fears of going to sleep – here they are glad and quite calm to start. They are boys who have already faced death and have come for help and relief and have confidence they will get just that. One can’t but be glad and do everything possible to try to give it.”

The horrors of D-Day

“I’ve been busy straight through and it was kinda like standing in a river trying to stop the flow. We’ve operated or worked on very serious cases that would die if they were moved further back. Our operations have been only on massive abdominal, chest, and head wounds and cases where an arm or leg is about blown away. We are working on shifts of 24 and 36 hours. We run shifts every day and each one rests every other night. If there is a particularly heavy flow of casualties, we all run straight through until it lightens. “

Loyd did not bathe or change his clothes until two weeks after D-Day and for more than a month he slept in a foxhole instead of on top of the ground, Loyd only complained once: “I know the day when you haven’t slept all night because shells screamed and then you must stand and work while dive bombing and strafing goes on because you’re in the midst of work you can’t stop and, when that is finished, the peak of futility is reached when you look in and see 20 or more men waiting that were shot through the chest and abdomen. Practically every man would have been given the slimiest hope of recovery. The stamina, the being accustomed to all weather and the desperate will to live make them able to withstand terrific injuries.”

Memories from the younger Dr. Osteen

“Accompanying my father on his nightly rounds as a teenager was an opportunity for me to learn how to interact politely, respectfully, effectively and efficiently with an anxious patient”

“The sights, sounds and smells of mass casualties, the grotesque wounds, the innocent civilians, the conflicted feelings of helping an enemy, the mistakes and errors, the triumphs and failure probably affected doctors differently. Some of the effects-experience, maturity, and knowledge were positive. For others the negative effects-alcoholism, depression and suicide were all too serious. For most doctors, like my father, it’s hard to know. My father had an air on imperturbability and resignation. Perhaps he had seen so many ugly things he was shocked by nothing.”

“He thought of himself first and foremost as a doctor. He might have paid lip service to his roles as husband and father but his being was inseparable from medicine.””

So you can see, Loyd Osteen was indeed one of the “Greatest Generation”. His son, Bob, and my oldest friend, died in 2022 after a distinguished, life long career as a surgeon and teacher at Harvard Medical School. In January of this year, at a commemorative service in Bob’s honor, numerous Harvard Medical School professors spoke.

Here is what they said about Bob:

“He was an icon of American surgery.”

“An internationally recognized oncology surgeon.”

“A teacher, such as Bob, affects eternity.”

“He had impeccable judgement and was the surgeon I most wanted to emulate.”

“The big brother I never had.”

“If we did not have a Bob Osteen, we would have to invent one.”

As we approach the 78th anniversary of D-Day it is most fitting that we celebrate the lives and contributions of these extraordinary physicians - Loyd Osteen and his son, Bob.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Savannah doctor behind lines D-Day World War II Loyd Osteen memories