If it’s all Greek to you, Emily Wilson’s new translation of ‘The Iliad’ may be worth a read

Though Homer’s “The Iliad” has become nearly synonymous with elite scholars, bards performed it in public and private, cementing its presence in ancient Greek culture.

Passing through oral tradition and having its life extended by translation, “The Iliad” has enchanted modern and ancient readers and scholars for thousands of years. And now Emily Wilson has produced a new translation of Homer’s epic poem.

Wilson is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and the first woman to publish a translation of “The Odyssey.” She’s a Yale-educated scholar whose work has won prestigious awards such as the Rome prize. Her translation of “The Iliad” was published on Tuesday and it is making waves.

Before you throw up your hands and say “it’s all Greek to me,” it’s worthwhile to think about why “The Iliad” has remained a seminal text.

Here’s a look at what “The Iliad” is, who Homer is, what you should know about Wilson’s new translation and a look at the relevancy of “The Iliad” today.

Related

What is ‘The Iliad’?

“The Iliad” is an epic poem (think long narrative poem) attributed to Homer (more on “Homer” later). It’s one of two poems attributed to him, the other is the Odyssey. Written in dactylic hexameter (the epic meter), the poem spans over 15,000 lines.

A precise date of “The Iliad” is unknown, but it’s usually dated to somewhere during the seventh or eighth century B.C.E.

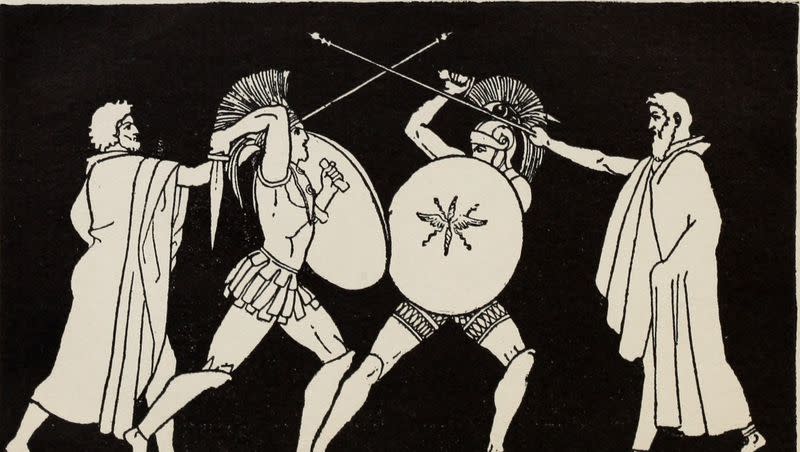

Divided into 24 books, “The Iliad” chronicles the end of the mythological Trojan War. An alliance of Greek city states bandied together to launch a siege on Troy because King Menelaus’s wife Helen trekked off to Troy with her lover Paris.

Menelaus enlisted his brother King Agamemnon and others to help. “The Iliad” depicts an ongoing quarrel between Agamemnon and famed warrior Achilles in addition to the relationship Olympian gods like Zeus, Hera, Athena, Diomedes and others have with the mortals.

While the quarrel between Agamemnon and Achilles takes center stage, there are plenty of other plot lines with the other main and secondary characters: Hector, Patroclus, Briseis, Helen, Paris, Priam, Andromache, Nestor, Ajax, Chryseis, Hecuba, Aphrodite, Aeneas and dozens more (it is an epic after all).

With themes like fate, undying honor, pride and anger as well as customs like hospitality and funeral practices, the poem offers a glimpse into ancient Hellenic mythology, religion, history, life and perceptions of war, morals and ethics.

It’s generally accepted that “The Iliad” was “composed for performance,” according to an article published on the University of Michigan website.

“In general, the number of Homeric papyri is staggering, confirming the overwhelming presence of the poems in the education and literary culture of the ancient world,” the article said. “Moreover, Homer would often transgress the boundaries of conventional education to enter the realm of everyday life.”

In other words, Homer’s “The Iliad” was everywhere in the ancient world. As Greek city states like Athens, Thebes, Rhodes, Sparta and other developed, “The Iliad” endured as a Panhellenic national epic (though it’s important to note city states ruled themselves).

Who is Homer?

So, who is Homer? Is he some sort of ancient Greek equivalent to F. Scott Fitzgerald or J.D. Salinger? The question of who wrote “The Iliad” is still debated.

“That there was an epic poet called Homer and that he played the primary part in shaping ‘The Iliad’ and ‘The Odyssey’ — so much may be said to be probable,” Geoffrey S. Kirk wrote for Britannica. “If this assumption is accepted, then Homer must assuredly be one of the greatest of the world’s literary artists.”

There are different schools of thought on how much Homer was involved and how exactly “The Iliad” came to be.

Some scholars see “The Iliad” as a collection of poems that several different poets contributed to and it consolidated into one narrative poem under Homer’s name, according to Peter T. Struck of University of Pennsylvania.

As scholar Gregory Nagy theorized, the name Homer can be be understood to “not refer to an individual at all” but instead it could show “the composition of the poems as a collective effort.” Others have floated different theories for who wrote “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey.”

If this sounds murky, that’s because it is. While scholars generally see “The Iliad” as having a primary author with contributions from different poets weaved in throughout, there’s still ongoing debate about the “Homeric question” and the dating of “The Iliad.”

What to know about Emily Wilson’s new translation of ‘The Iliad’

Wilson released her translation of “The Iliad” after she translated “The Odyssey.”

For her translation of “The Odyssey,” she received praise for doing a line to line translation and producing an accessible translation. For every line of Greek, Wilson rendered it into one line of English. Doing a one-to-one translation like this is difficult because one word of Greek doesn’t always translate into one word in English.

Since “The Odyssey” is a metered poem (dactylic hexameter), Wilson had to make a decision about how to render that into English: she chose iambic pentameter and simple language for her translation.

“Her poem has the stamp of a clear and consistent vision, and brings Odysseus home to us again — cunning, eloquent, murderous; in sum, complicated,” Classics expert Richard H. Armstrong wrote for Los Angeles Review of Books.

She brought that same kind of energy to “The Iliad.”

“Goddess, sing of the cataclysmic wrath / of great Achilles, son of Peleus, / which caused the Greeks immeasurable pain / and sent so many noble souls of heroes / to Hades, and made men the spoils of dogs, / a banquet for the birds, and so the plan / of Zeus unfolded — starting with the conflict / between great Agamemnon, lord of men, / and glorious Achilles,” read the opening lines of her poem.

With the exclusion of “cataclysmic,” Wilson sticks to accessible language and maintains her use of iambic pentameter. She changes the word order from the start — it’s necessary to change the word order when translation from Greek to English, but some translators have historically decided to have “wrath” as the first word of the translation since it’s the first word of the Greek.

Especially if a person is unfamiliar with the complicated narrative(s) of “The Iliad,” Wilson translates the Greek into an accessible read.

“Wilson offers an ‘Iliad’ that a modern reader can consume without excessive mental interruption — perhaps like an Ionian peasant would have, as part of the poem’s original listening rather than reading audience,” Graeme Wood wrote for The Atlantic.

It’s a “novice-friendly” book, as Wood pointed out, but the contemporary sound to the text makes them sound less “like the wild selves preserved in the Greek.”

Wood’s analysis of “The Iliad” gets at one of the central issues with translation: whenever someone translates a text, something is lost in translation: even the meaning of a specific word can change one’s understanding of a character or event.

Moreover, it’s difficult to encapsulate the soul of a text in a translation.

As Edith Hall observed in The Guardian, “Although absolutely true to his emotional pungency, sometimes Wilson does not rise to the sheer grandeur and sublimity of Homer’s evocations of cosmic scale, meteorological chaos and battlefield pandemonium for which he was so admired in antiquity.”

Still, Wilson’s “The Iliad” reveals something bigger than the text itself: it shows the poem’s outsized presence in literature.

Related

Why ‘The Iliad’ is still relevant today

Though “The Iliad” has experienced some obstacles in recent decades, it remains a relevant and well-read text.

A barrier of entry to “The Iliad” is the language of the text itself. While translations are a way to access the text without knowing ancient Greek, the language barrier still exists. While ancient Greek used to be taught in some classrooms, as Pulitzer Prize winner Daniel Walker Howe observed, teaching of ancient Greek has “vanished from most American classrooms.”

That said, “The Iliad” still appears on syllabi, albeit in a translated form. It’s also been rendered into more contemporary forms, like rap.

Professor Brandon Bourgeois used GarageBand to make “The Iliad” into “a rap lecture in staccato bursts” to share with his students.

Beyond reading lists and rap lecture, “The Iliad” remains relevant because of what it shows about the ancient world and how it has been received.

The poem gives a glimpse into a record of one of the oldest civilizations. Sure, it has mythological and fictional elements, but those mythological elements provide perspective on the way ancient Hellenes worshiped. The poem also supplies readers with an understanding of how social classes may have worked, attitudes toward war and what sorts of forces ancient Hellenes believed in.

“The Iliad” was also genre-defining in that it shaped the definition of an epic.

“By force of its prestige, ‘The Iliad’ sets the standard for the definition of the word epic: an expansive poem of enormous scope, composed in an archaic and superbly elevated style of language, concerning the wondrous deeds of heroes,” Nagy wrote. “That these deeds were meant to arouse a sense of wonder or marvel is difficult for the modern mind to comprehend, especially in a time when even such words as wonderful or marvelous have lost much of their evocative power.”

Beyond what can be learned from “The Iliad” itself, the poem has inspired other artists, which contributes to its longevity.

Writers, artists, musicians, shows and movies and inspired by “The Iliad” are too numerous to list comprehensively, but here’s a few: Andy Warhol, Peter Paul Reubens, Led Zeppelin, Christopher Marlowe, “Star Trek,” “The Simpsons,” Pat Barker, Bob Dylan and more.

So, while Wilson’s translation of “The Iliad” may just seem like a rehashing of a thousands-year-old poem, it shows there’s still serious reckoning that people can do with the text.