Green Book project reveals which Greater Akron spots were safe havens during Jim Crow era

Akron’s “Little Harlem” neighborhood was buzzing with excitement Sept. 24, 1935, when up-and-coming boxer Joe Louis stepped into the ring to fight former heavyweight champion Maxie Baer.

People crowded into cafes, bars and hotels in what was then a thriving Black neighborhood just north of downtown to hear the radio play-by-play of the fight 450 miles away in Yankee Stadium.

“Maxie is bleeding freely from the nose!” a radio blared inside Leonard Forman’s Green Turtle Hotel off of North Howard Street.

“There was a roar from the assembled fight fans that could be heard to the High Level bridge,” the Akron Beacon Journal reported at the time as Louis won.

All that remains of Akron’s Little Harlem now is a memorial, memories and scraps of history buried in old newspaper clippings, advertisements and public records.

Students at the University of Akron are now working to piece it together — along with Black history in all of Greater Akron — as part of a restorative history project aimed at better understanding our past.

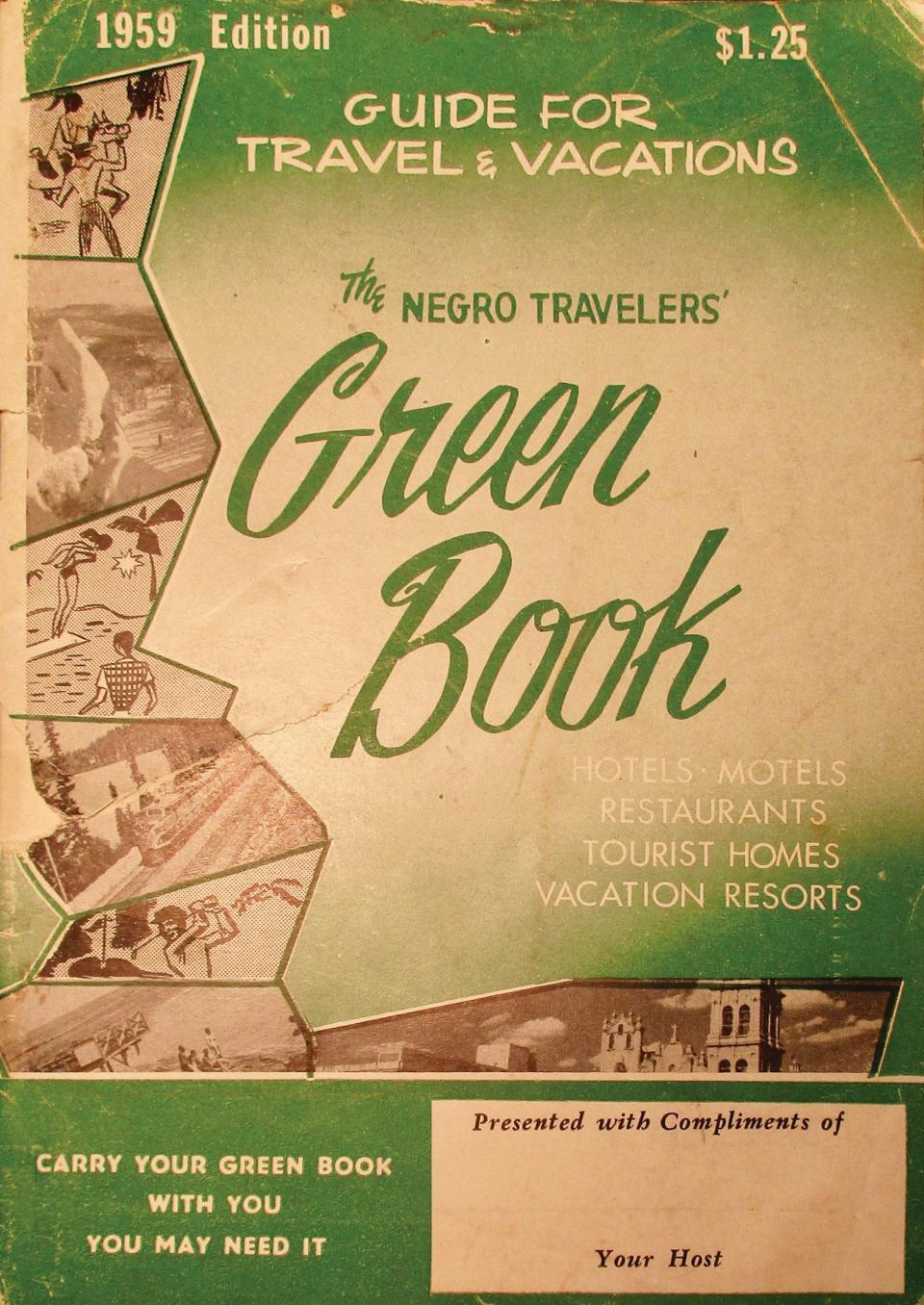

Project rooted in 'The Negro Motorist Green Book' tells the story

The project, which started in Cleveland, is rooted in the “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” an annual travel guide published between 1936 and 1966 to help Black motorists travel safely during the Jim Crow era.

The Black-owned Green Turtle hotel, which was near where Luigi’s is today in the Northside District, was one of a handful of Akron spots highlighted in the Green Book.

But UA students are reaching beyond the Green Book, helping to create a free online map that details all Black-owned and Black-friendly businesses and entertainment venues at the time throughout Northeast Ohio.

In Greater Akron, the project details everything from beauty parlors, farms and eateries to service stations, summer camps and golf courses in an area that stretches from Peninsula through Akron into East Canton.

Cleveland State University History Professor Mark Souther, working with the Cuyahoga Valley National Park, launched the project — greenbookcleveland.org — in 2021.

Local history of the Jim Crow era, Summit County's ties to the Ku Klux Klan

Between the U.S. Civil War and Civil Rights movement, about 6 million African Americans left the U.S. South and migrated to cities in the north, midwest and west seeking social, economic and political freedom.

Black people found discrimination in their new homes, too.

In Summit County, for example, the chapter of the Ku Klux Klan reported having 50,000 members during the 1920s, making it the largest local chapter in the country at that time. At some point, the county sheriff, the Akron mayor, judges, school board members and other public officials were part of the racist organization.

That may help explain repeated police raids, fires and other incidents documented in Greater Akron by the Green Book project during those years.

But the new arrivals also found success, building businesses, families and organizations specifically aimed at promoting equality and success for Black residents in Greater Akron.

UA history professor Greg Wilson said he learned of greenbookcleveland.org last summer while preparing to teach the first graduate seminar for the university’s new master’s degree program in applied history and public humanities.

The interdisciplinary program focuses on public history and prepares students for careers in humanities organizations, businesses, government or the nonprofit sector.

One of Wilson’s students, Rose Vance-Grom, is a fifth-generation Akronite from Firestone Park. But like many others, she said she, too, was unaware of much of the history she researched for greenbookcleveland.org. Most of her work focused on Akron’s Little Harlem and Brady Lake near Kent.

Trying to see a clear picture of history, she said, is not always easy. Researchers rely on the archives of larger newspapers, like the Beacon Journal, but sometimes find conflicting information in small, Black-owned publications like The Call & Post in Cleveland or the Pittsburgh Courier, both of which covered Akron’s Black community.

Brady Lake, for instance, hosted a lot of Black entertainers, Vance-Grom said.

“But it was hard to differentiate what was open to Black people” or if they just entertained white people, she said. “It was hard to nail down if it was segregated or not and how that worked.”

She ultimately concluded that Brady Lake appeared to welcome Black people, but not all of the time. A 1935 article in the Call & Post about a jazz concert noted that Brady Lake “will be turned over to our people … for the first time in three years.”

One of Vance-Grom’s favorite discoveries, she said, is a mural painted on the back of Dirty River Bicycle Works in Akron’s Northside.

It features images of Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald and other Black superstars who frequented Akron’s Little Harlem during its heyday, when a half-dozen or more small jazz clubs hosted musicians nearly every night of the week.

Here’s a look at a few of the Greater Akron people and sites that are part of Black history:

Blossom site originally known as Stonibrook, a camp planned for Black children

Stonibrook in the 1950s was a 45-acre wooded site with cabins near the corner of Northampton and Akron-Peninsula roads.

The Beacon Journal reported that a “mystery fire” destroyed several cabins there in the early morning hours of July 1, 1957. The newspaper said the property was owned by William Johnson, 40, and that a Cleveland fire marshal ruled it arson.

But the story didn’t mention that Johnson was Black or that he and his wife, Ann, bought the property earlier that year and planned to turn it into a summer camp for Black children.

The Call & Post, however, went further. A reporter visited the site, interviewed Johnson and took pictures of people cleaning up the burned mess.

It reported Johnson was a World War II veteran who went on to work as a physicist for the Atomic Energy Commission.

He and Ann bought the wooded property — that included three lakes fed by spring water and several lodges, all with electricity — earlier that year. They planned to invest $250,000, the equivalent of more than $2.5 million today, to create the camp.

The arson, at least initially, didn’t change those plans.

“If I die I am going to make certain that this property is made available to Negro youth, who have no opportunity to attend a summer camp,” Johnson told the Call & Post days after arson.

Johnson said he was told during World War II that they were fighting for democracy abroad.

“Well, I’m fighting for it right here at home now, and if necessary, they may come to call this Johnson’s tomb,” Johnson told the newspaper.

It’s not clear whether the Johnsons ever tried to rebuild there or anywhere else.

Neither Green Book researchers nor the Beacon Journal could find more information on the Johnsons or the camp. Searches of old newspapers, records of the Atomic Energy Commission and ancestry.com turned up nothing.

But Green Book researchers were able to add local context to what was happening at the time of the arson.

Souther pointed out the Johnsons were not listed as owners in historical property records.

“It raises the question of whether this was actually in someone else’s name on their behalf, which was not an uncommon practice when African Americans were trying to acquire property in areas that were unlikely to welcome them, to put it mildly,” he said.

And that swath of territory in the 1950s was one of them.

At the time, nearby Cuyahoga Falls was known as one of thousands of “sundown towns” across the U.S., places where Black people and other non-whites and non-Christians were not welcome after dark, Green Book historians said.

Researchers with the Cuyahoga Valley National Park, who are also part of the Green Book project, also discovered there was a possible Ku Klux Klan office on Northampton Road during the time of the arson.

Two African American clubs nearby — Lake Glen and the Drift Inn/Cabin Club — were repeatedly targeted by local law enforcement and health officials at the time, who accused the clubs of illegal liquor sales, gambling and other violations.

The Call & Post at the time called the targeted enforcement racist.

It’s unclear how much of this the Johnsons knew when they bought Stonibrook, nor what they learned after the arson.

But in 1966, the Musical Arts Association purchased the former Stonibrook property and it’s now part of Blossom Music Center and the Cuyahoga Valley National Park.

Stonibrook is “still a story that’s unfolding bit by bit as we continue to learn more,” Souther said.

Green Turtle Hotel & Green Turtle Cafe at forefront of advocacy for African American rights

The Green Turtle Hotel, one of the places Akronites gathered to hear the Joe Louis fight in 1935, was at 68 Furnace St., which is now part of a parking lot that serves the Northside District.

Before it opened, however, it was home to the Green Turtle Cafe. From 1918-1920, it was owned by Raleigh Prince and Leonard H. Forman. Forman later took over and the hotel remained on Furnace and the cafe moved nearby to 55 N. Howard St.

Forman, born in 1888, worked as a servant for a family in Philadelphia before moving to Akron in 1920, where he lived on Edgewood Avenue, Green Book project researchers said.

Though he was best known for his hotel and cafe, Forman’s activity in fraternal and social groups helped illustrate African Americans’ evolving roles in politics and power at the time.

In 1928, Forman and two others formed the Summit County Colored Democratic Club in Akron “to promote political and civic welfare … especially among those of the colored race.”

In 1939, Forman was a founding member of the Frontiers Service Club, the second chapter of “a National Service Group among Negro businesses and professional men.”

And in 1946, Forman joined the Akron Business Alliance, which appears to be a forerunner to the chamber of commerce.

The hotel, Green Book researchers said, was an “active location that hosted powerful local political figures and was at the forefront of advocacy for African American rights.”

Forman died in 1951, and his wife, Oda, sold the Green Turtle just days before she died in 1957.

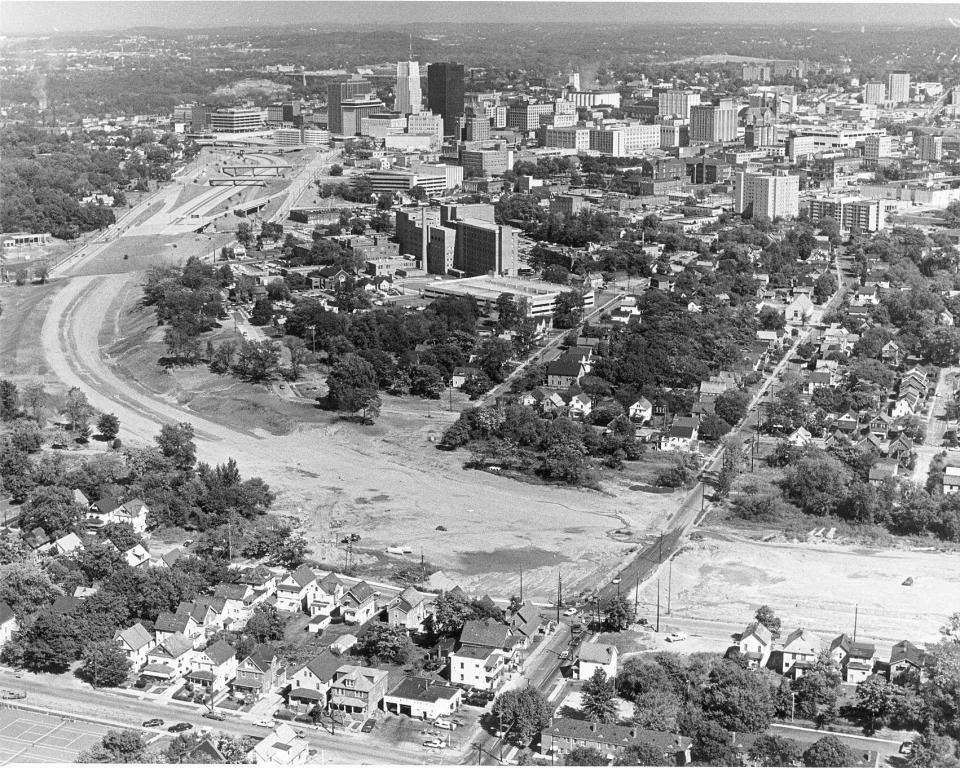

Sites of both the cafe and hotel were likely torn down with much of the neighborhood for the Akron Innerbelt project that decimated Little Harlem, along with Black neighborhoods near downtown.

The Ritz Theater one of few buildings still standing in Akron’s Little Harlem

The Ritz Theater at 100 N. Howard St. was built in 1942.

It showed major movies to the general public, but Beacon Journal advertising for The Ritz indicates it also showed the “All-American News,” a newsreel that began that same year to serve African Americans.

The newsreels were “some of the best and first consciously produced, positive images of Black people” living their daily lives, contributing to the war effort, and making history, according to “Reel Black Talk,” a book about African American filmmakers.

The Ritz also had live performances.

A Beacon Journal ad in 1955 promoted a show there by The Five Keys, a wildly popular African American rhythm and blues group.

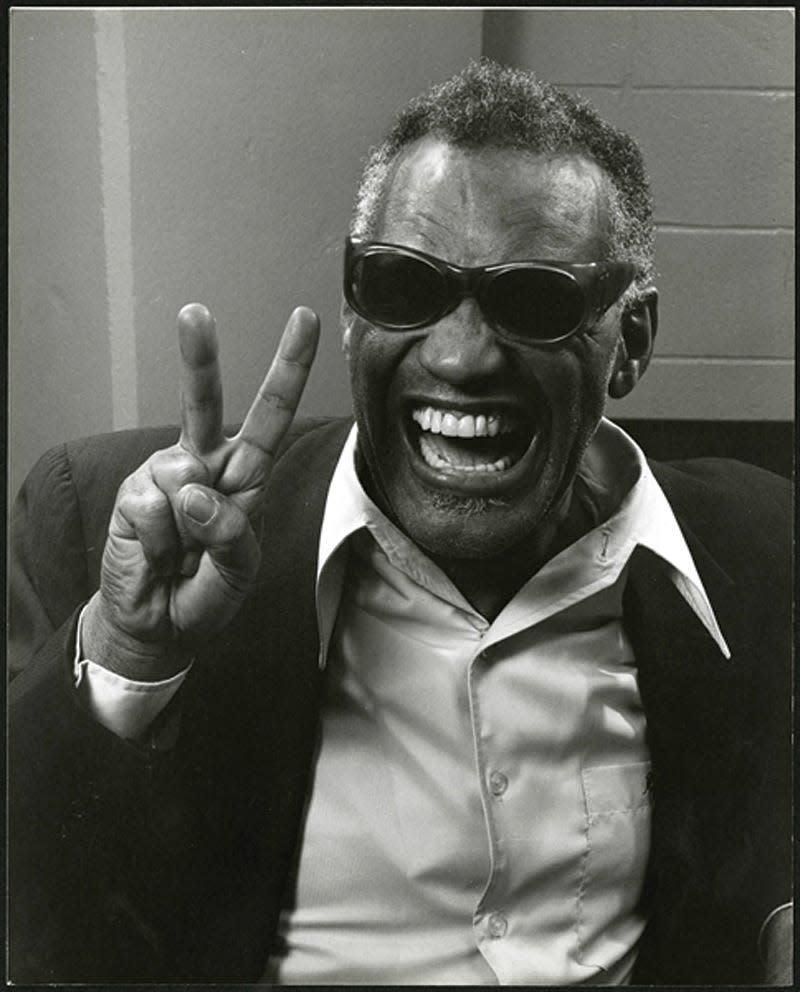

Ray Charles, the iconic singer and songwriter, received second-billing in the ad, which promoted his song, “I’ve Got a Woman.”

Green Book researchers haven’t yet included the Ritz on the website, but it’s one of the few buildings of Little Harlem that remains intact after the Innerbelt project.

It’s known now as the Interbelt Nite Club, one of the oldest LGBTQ+ clubs in Akron.

The Interbelt night club opened in 1970s with a name likely inspired by the Innerbelt project. Beacon Journal clippings at the time show there was some general confusion at the time about whether the project was “inner”-belt or “inter”-belt.

The city finally landed on “innerbelt.” The name of the nightclub has never changed.

Black World War II veteran builds Clearview public golf course for all in Stark County

William J. Powell, a grandson of Alabama slaves, moved to Minerva as a boy because his dad was looking for a job at local brick and clay companies.

There, he and his brother worked as caddies at a local golf course, earning 35 cents per bag.

"I had never seen anything so beautiful," Powell later wrote in his book, "Clearview: America's Course."

Powell was fascinated by the grounds, the streams, the sand bunkers and the players who "hit the balls so high and so far into the air...I couldn't understand how they did it, and I couldn't wait to try it myself."

At the time, Powell’s mom worked for a Minerva doctor. And when the doctor found out he wanted to golf, he made Powell his playing partner every weekday at noon.

Powell went on to play in golf tournaments as a teenager and was on the golf team at Wilberforce College, a historically black university in Xenia.

After serving in World War II, he came home to Stark County and discovered he, as a Black person, was excluded from golfing at many area courses.

While working as a security guard at Timken, Powell pursued a long-held dream of building his own course.

With financing from his brother and two doctors, he bought a 78-acre dairy farm in East Canton. After his shift at Timken was over, he worked building a course on the farm.

It took him two years, but Powell opened Clearview Golf Club in 1948. It was the first course in the U.S. designed, built and owned by an African American.

Powell called it “America’s Course,” and it was open to all.

In 1996, Powell was inducted in the National Black Golf Hall of Fame. The next year, he received an honorary PGA membership.

The course, on the National Register of Historical Places, remains open today and is managed by Powell’s children, Larry Powell and Renee Powell.

Renee Powell is a professional golfer who played on the US-based LPGA Tour.

She is now the head professional at Clearview.

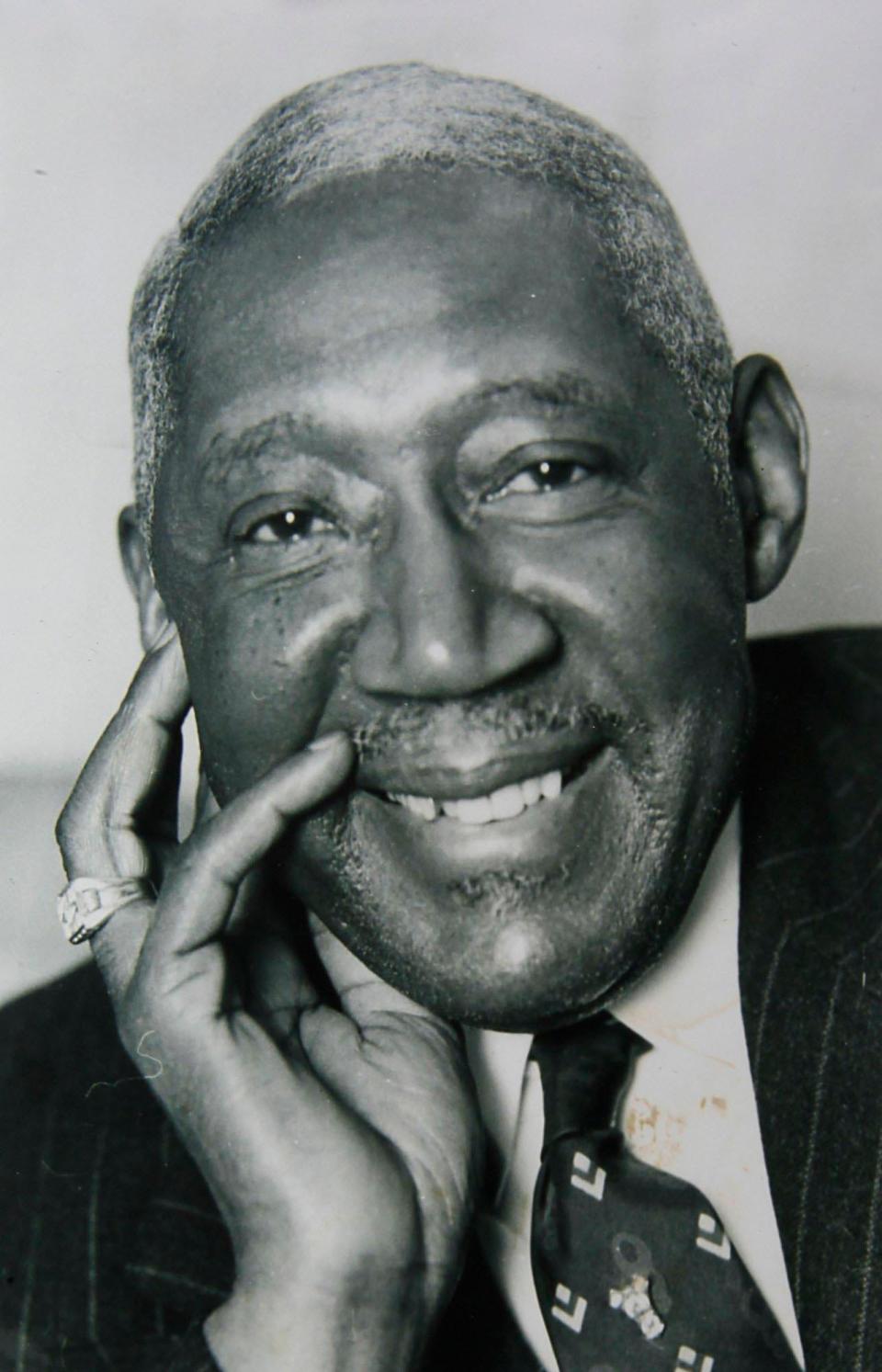

Mathews/Matthews Hotel served as anchor for Akron’s Little Harlem

No other Akron business appeared in the Green Book more than the Mathews Hotel.

It was listed as a safe haven for Black travelers from 1938 to 1967, Green Book researchers said.

The hotel at 77 N. Howard St. is gone, but a monument to this anchor of Little Harlem stands at the corner of Howard Street and Martin Luther King Boulevard.

The Mathews hotel and barber shop was owned by George W. Mathews. He was born Feb. 15, 1887, on a cotton farm near Thomaston, Georgia, the eldest of 10 sons born to a sharecropper family, the Beacon Journal reported.

Mathews began helping his family tend the field as soon as he could walk. But he longed for something more and left home when he was 21 with $3.50 in his pockets.

He ended up in Montgomery, Alabama, dumpster diving for food before landing a job as a stock boy in a hardware store for $6 a week.

“I always got to work early and never worked less than 12 hours a day,” Mathews told the Beacon Journal in the 1950s.

The Alabama hardware store owner also owned a hotel where Mathews worked as a porter. There, he earned $5 a week, plus tips. “I saved the $5 and lived off my personality,” Mathews said during the interview.

In 1919, after saving $1,100, Mathews treated himself to a vacation, hopping a train north to Toledo to see a fight between heavyweight boxers Jack Dempsey and Jess Willard.

He also took a side trip to Akron and was smitten with the city booming with prosperity because of a burgeoning rubber industry. Mathews moved to Akron the following year, buying an 11-room boarding house near Main and Furnace streets and opening a barber shop on the first floor.

In 1925, he converted the rooming house into a hotel with a sign carved above the entrance that read “HOTEL MATTHEWS.”

The spelling error, adding an extra “t” to Matthews, apparently didn’t bother Mathews because it remained for 50 years as Mathews worked at the barbershop from noon until dinnertime and then returned to the hotel in the evening, where he worked until 1 a.m.

By 1964, Mathews had become so successful, he established a $25,000 scholarship endowment for UA “students demonstrating ability, potential and financial need” with no distinction made as “to race, creed, color, sex or national origin.”

“My only regret is that I can’t double the size of the gift,” Mathews said at the time, though the scholarship fund continues to help students today.

Mathews’ wife died in 1969. The Innerbelt project demolished his hotel and barber shop a few years later, and Mathews, at 95, died in 1982.

But Hotel Mathews and the Black business district where it thrived are immortalized by the $125,000 monument built in 2012.

The brick monument not only replicates the front entrance of the Mathews hotel, but also includes the misspelling on the sign: Matthews.

Share your Greater Akron Black history stories

The Green Book project, which already pinpoints scores of sites important to Black people during the first part of the 20th century, is ongoing and will soon expand to gathering oral histories from people who remember these locations, or recall their parents’ or grandparents’ stories about them.

To contribute, go to greenbookcleveland.org and write your memories in a provided box under each site listed.

You can also email your memories to info@greenbookcleveland.org or by traditional mail to Greg Wilson, c/o 216 Arts & Sciences, UA history department, University of Akron, Akron, Ohio, 44325-1902.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Researchers rebuild Greater Akron Black history through Green Book