Grenade-dropping drones, a paranoid president, guards who ran: Latest on Haiti assassination

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Two of his own guards were informants. The alleged killers, several now in custody, knew his every move. One alleged mastermind even secured an apartment nearby — purportedly watching his estate for 10 months before running reconnaissance patrols with Colombian hit men shortly before the middle-of-the-night ambush.

The Colombian teams, accompanied by Haitian police officers, swarmed the Haitian presidential compound above the hills in Port-au-Prince with military precision. Each team leader is described by police as carrying a Samsung Galaxy smartphone — to photograph the president’s corpse and assure the masterminds of his death.

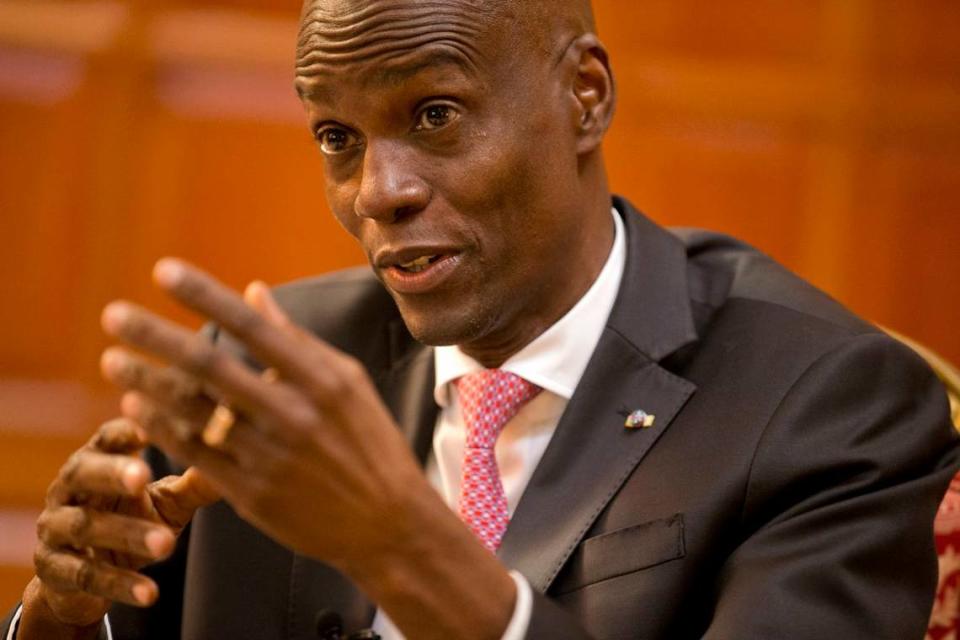

Haitian President Jovenel Moïse was an easy target, far more vulnerable to an attack by his own guards and a team of former Colombian soldiers than first thought in the immediate aftermath of his July 7 assassination, according to a 124-page Haiti National Police report obtained by the Miami Herald.

“During this attack, [his guards] showed such passivity that they showed no intention of defending the Head of State, let alone the presidential family,” the Haiti police investigators concluded. “By their attitude, they facilitated the access of the attackers to the residence of the President.“

Moïse, 53, was not only fatally wounded after being shot multiple times, but also “severely beaten” inside his bedroom while his wife, Martine, was seriously wounded and left for dead. She survived and has since declared her intentions to seek the presidency.

A paranoid president who trusted no one, Moïse ran his own camera surveillance system and was a man without friends. As automatic gunfire rang out the night of his shocking murder and grenades dropped from drones during a span of 30 to 45 minutes, the president frantically called for reinforcements, alerting several police officials that his life was in danger.

“The President’s appeals for help, addressed to those in charge of the presidential security structure, were in vain,” police said in the report.

He made calls to Divisional Commissioner Jean Laguel Civil, the coordinator of the presidential security now accused in the police report of providing $80,000 in cash to 80 agents on the day of the attack to get them to stand down; and to Police Commissioner Dimitri Hérard, the head of the palace guards, known as the General Security Unit of the National Palace (USGPN), who is accused in the report of not only being part of the planning and one of the informants but of providing ammunition and arms to the Colombians.

He also called Director General of the Police Léon Charles and Inspector General André Jonas Vladimir Paraison.

The first high-ranking officer to arrive, Paraison, told investigators that while making arrangements for the first lady to be transported to the hospital, he entered the presidential couple’s room with their son and found the president’s corpse.

Under Haitian law, an arrest and detention does not mean formal charges have been filed. A judge has a prescribed period of time to investigate the allegations and decide whether the case will proceed.

The police report lays out the alleged roles of many of the 44 individuals in custody, including 18 former members of the Colombian military who had abruptly moved out of a boutique hotel and into the home of another key suspect, a convicted drug trafficker, four days before the killing. What it doesn’t do is answer many of the core mysteries surrounding the attack.

Among those questions was who were the individuals on an infamous video call described by Moïse’s wife to police? The widow told police that one of the killers contacted “a person by video call to provide a description of the place and the president” before her husband was riddled with bullets. Also, who financed the expensive and expansive operation — and why?

Police also do not identify the murder weapon, not even its caliber. The report says Moïse’s home was ransacked before the suspects left with undisclosed “large sums of money” in two briefcases, the surveillance camera equipment and, according to his wife, a document.

But perhaps the biggest question is when and how did a plan by a Haitian-American pastor and doctor to topple Moïse metastasize into an assassination plot falsely invoking the U.S. government? Several suspects told police that they were informed in the weeks before the raid that the plan had the backing of U.S. law enforcement agencies. Amid the gunfire, one of the suspects now in custody, James Solages, claimed it was a DEA, U.S. Army and U.S. Marshals operation.

“Pa tire!” he yelled, a warning in Creole to the president’s guards not to shoot.

More than two months after the assassination, the probe appears to be barely moving since the initial arrests — a roundup that included 20 Haitian police officers, an ex-drug trafficker and three South Floridians. Several prominent personalities and politicians have become linked to the investigation, including the current prime minister, Ariel Henry, tapped by Moïse to lead a consensus government just days before his killing.

Port-au-Prince’s lead prosecutor, who weeks ago had been provided with the investigative documents, including hundreds of additional pages in testimony and exhibits, asked the investigative judge in the case on Tuesday to charge Henry and bar him from leaving the country. He cited two phone calls from one of the key suspects in the case. The police report shows that Joseph Felix Badio called Henry at 4:03 a.m. and 4:20 a.m., almost three hours after Moïse was killed, but it does not indicate if they actually spoke.

In a press statement, the prime minister’s office said on the night in question he received “countless calls from all kinds of people, who on hearing the terrible news, were worried about his personal safety.” He added that “conversations with individuals against whom charges are brought, may not, under any circumstances, be used for incriminating anyone.”

Legal experts have said that the prosecutor, Bed-Ford Claude, who had been fired by Henry the day before he made the request, had no legal authority to mount a parallel probe into an active investigation. After the case had been transferred over to an investigative judge, whose work is similar to a U.S. grand jury, Claude was required to stand down.

That judge, Garry Orélien, is the second to be assigned the murder investigation because the original judge quit the case, citing security concerns after one of his court clerks was found dead under mysterious circumstances.

In one of his first acts, Orélien this past week summoned Moïse’s widow to appear for questioning. In statements to police, Martine Moïse said there was supposed to be a staff of approximately 30 to 50 police officers assigned to guard the presidential residence.

But on the night of the attack, according to police, there were only seven officers present, one of whom, a now-arrested team leader of the presidential guards, left his post at 4 p.m. without authorization “on the pretext that he was settling a personal matter.”

The officer, Divisional Inspector Conrad Bastien, was initially unreachable, police say, while all of Pétionville, where the president lived, was in turmoil after the killing

“Strangely, he only returned after the assassination of the Head of State, without providing any explanation for his prolonged absence from the post,” the police report said. Police described his behavior upon returning as “nonchalant.”

This attitude was in fact adopted by all the agents stationed at Moïse’s private residence, a home on a dimly lit dead-end street in the Pèlerin 5 neighborhood, police said.

Claiming they were outgunned, outmanned and not allowed inside the president’s home, the six guards left on duty that night failed to activate an evacuation plan. Instead, they fled, with one even admitting to undressing and leaving his weapon and ammunition under shrubs before seeking refuge in a nearby neighbor’s house, according to police.

In their effort to understand the complex plot, Haiti police investigators interrogated the Colombians, as well as two Haitian Americans, James Solages and Joseph Vincent, multiple times. Investigators also questioned Christian Emmanuel Sanon, the Haitian-American pastor and doctor who police consider one of the planners of the attack on the president. They have linked Sanon to the owner of a Miami-area security firm, Counter Terrorism Unit, or CTU, and one of his associates.

Haiti police say that CTU owner Antonio “Tony” Intriago, a Venezuelan émigré, and his associate, Arcángel Pretel Ortiz, collaborated with Sanon and were responsible for recruiting and hiring the Colombians implicated in the assassination of Moïse.

Intriago’s lawyers in Miami, Joseph Tesmond, Gilberto Lacayo and Christian Lacayo, strongly denied their client had any involvement in the deadly plot.

The lawyers said Intriago and Pretel Ortiz formed another company called CTU Federal Academy, and that the firm took out a loan of $172,000 and signed a contract with Sanon to provide security for him as part of his political plan to run for president in Haiti. The lawyers said it was Pretel Ortiz who recruited and hired the Colombians for that security job, though they acknowledged that Intriago met with them in Haiti.

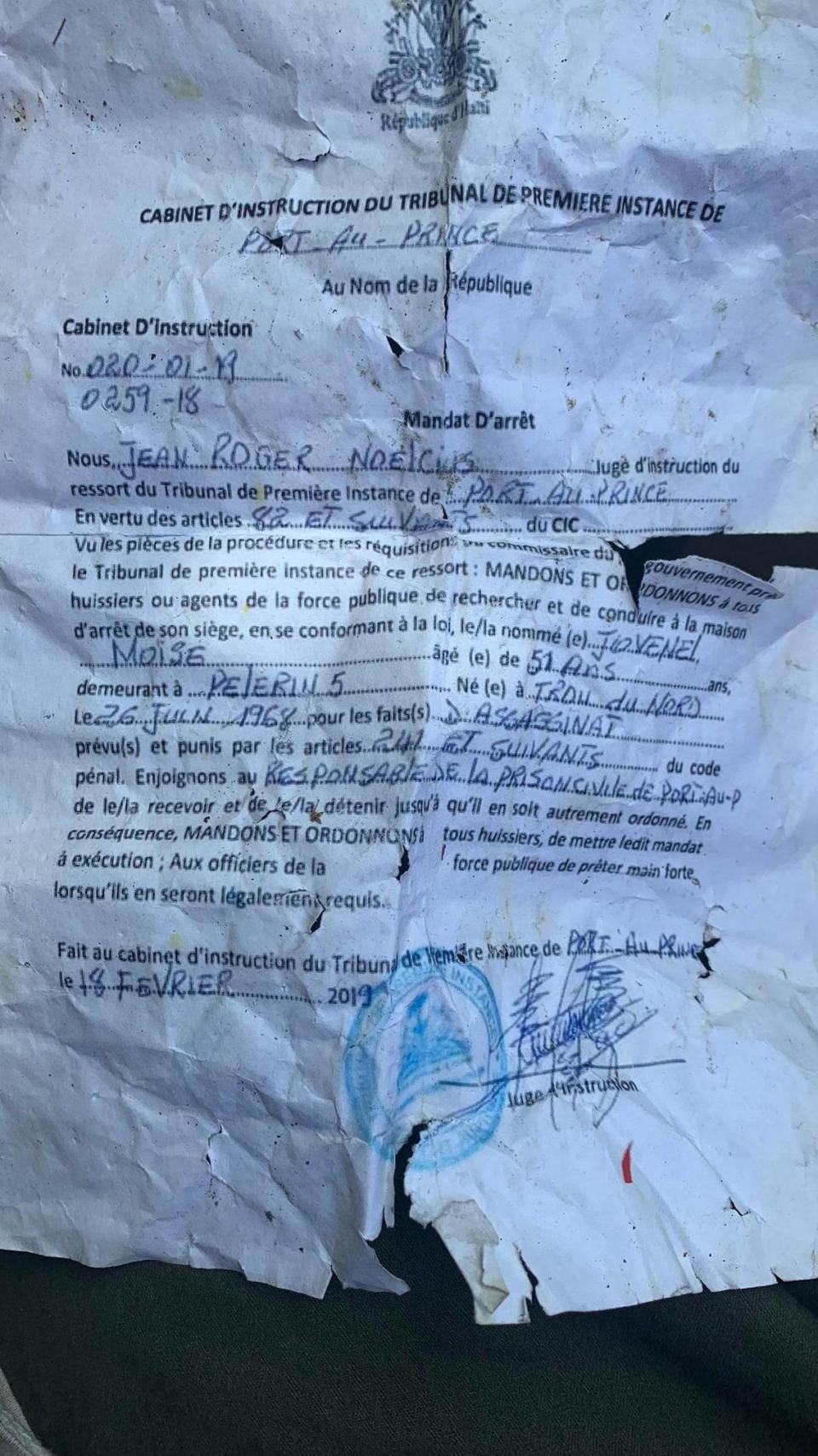

The lawyers said that early this year Intriago was told by Sanon and his supporters that the Haitian physician needed security services because he was going to seek the presidency during a regular election. They said Intriago only later became aware of an alternative plan to remove Moïse from office by arresting him upon the president’s return from a state visit to Turkey in June, and that a Haiti Superior Court justice sought his security company’s assistance.

“Intriago became aware of this change in plans because he became aware of the [Haiti] arrest warrant [for the president],” the lawyers said. But they stressed that their client was not involved in the arrest scheme or in the assassination plot. Haiti police investigators, citing testimony from a retired Colombian lieutenant in custody, describe Intriago as “one of the designers of this project,” the police report said. His partner, Ortiz Pretel, meanwhile, was “known as one of the bosses of the team,” the report added.

Arcángel Ortiz Pretel, who also went by the name Gabriel, could not be reached for comment for this article. In the past, when contacted by the Herald, he declined to discuss any alleged role in what happened in Haiti.

In South Florida, federal prosecutors are considering bringing charges against Intriago, Ortiz Pretel, Solages, Vincent and others who, according to the police documents, may have played supporting roles in trying to remove the Haitian president from power in violation of U.S. law, according to sources familiar with the U.S. investigation.

Sanon is in custody in Haiti. Neither Intriago nor Ortiz Pretel has been arrested.

The various suspects in custody have denied any personal involvement in the killing, though some of the Colombians point the finger at cohorts they allege actually entered Moïse’s bedroom while the rest stayed outside. Known as the Delta team, the group that allegedly penetrated the bedroom consisted of four Colombians, two of whom were killed by Haitian police during a firefight, a third who remains a fugitive and a fourth who is in custody, according to police.

Haitians may never truly know who actually fired the shot that killed their president and who had the means to finance the killing. The investigation has been mired in irregularities from the onset. Two judges and a court clerk involved in documenting evidence in the case have gone into hiding after receiving death threats when they refused to fabricate their reports.

The detained Colombians have also complained to lawyers in Haiti and to their president that they were subjected to torture during interrogations by Haitian authorities.

Still the information police extracted paints a troubling portrait of lapses in the president’s security, leaving him vulnerable to betrayal and murder. Among the facts that police allege in the report:

▪ Ten months before the assassination, Badio, a key suspect and former consultant in the ministry of justice who worked in the anti-corruption unit until his firing in May for violating unspecified ethical rules, rented an apartment near the president’s home. From a nearby mountaintop, Badio and his alleged accomplices watched the yard.

▪ According to statements from the Colombians, Badio told them he had an informant in Moïse’s circle who kept him apprised of the president’s activities. On the night of the attack, the main gate to the residence was left open as had been agreed upon by Badio, who is also accused of providing bribes to palace guards to execute the mission, the Colombians further alleged.

▪ The report additionally alleges that a divisional inspector, Jude Laurent, who was on duty the night of the attack and worked as the president’s driver, was among the informants and was in constant communication with Badio and another suspect, Marie Jude Gilbert Dragon, during the evening either before or after the assassination. Dragon, an ex-police commissioner and former rebel leader who played a key role in the 2004 coup that ousted Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, was accused of being the one who designed DEA tags for the vests used during the attack. Dragon and Laurent both denied any involvement in the killing during questioning by police investigators. They are both in custody.

▪ Hérard, the now-incarcerated police commissioner who personally knew at least three of the jailed Haitian suspects, was heavily involved in the planning and supplied ammunition and arms, according to a number of the detained suspects. Several suspects have identified him as being an informant on the president’s activities. In his interrogation by police, he denied any involvement and minimized his relationship with some of the accused despite attending the same Ecuador military training school with one, Dragon.

▪ Two of the arrested South Florida Haitians, Vincent and Solages, who have said they were employed as translators, informed police that Badio told the group that Civil, the presidential security coordinator, had $80,000 in hand to bribe 80 palace guards. Attorney Reynold Georges, who represents the detained Civil, told the Herald that the accusation is a lie and an attempt to “persecute” his client, who he said had nothing to do with the attack.

▪ Described as one of the brains behind the operation, Badio logged 290 calls between May and June with a Cinéus Francis Alexis, whose cell was transmitting from Pétionville at 2:04 a.m. on the night of the attack and later in the vicinity of the National Palace.

According to the report, Alexis had been “in contact before, during and after the assassination of the President of the Republic with several numbers” belonging to key suspects in the attack. Alexis also had 203 calls during the same time period with Rudolph Jaar, convicted in a U.S. courtroom of drug trafficking, whose Haitian home housed the Colombians, vehicles and weapons days ahead of the attack. Alexis also contacted two phone numbers belonging to former Haitian Senator Jean Joël Joseph, whose name on travel records is written as Joseph Joël John, at least 10 times.

The ex-senator, Jaar, Badio and Alexis are among those for whom Haiti police have issued arrest warrants, along with Mario Palacio Palacio. Known as Floro, Palacio Palacio is one of the Colombians who allegedly entered the president’s room, the police report said.

The night Moïse was shot was actually the second time in a span of weeks that his life was in danger, according to testimony from one of the Colombians in custody, and one of the Haitian Americans. .

Two weeks earlier, a plan to arrest Moïse, using a bogus arrest warrant, upon his return from a trip to Turkey was thwarted when a signal to act was never given, Jheyner Alberto Carmona Florez, an ex-Colombian soldier now in custody, told police. Another plan to employ disgruntled, masked Haitian police officers known as Fantôm 509 to grab the president was also aborted, according to Solages.

“It was planned to use the services of the members of the group called Fantôm 509 by providing them with seven assault rifles, including one that would have been hijacked” by Badio from the government’s anti-corruption unit, Solages told Haiti National Police investigators during one of several interrogations.

Police say rumors of Sanon’s subversive activities had reached Moïse prior to his assassination. While in his home, investigators found a notebook where Moïse had written “to check the full name and the phone number of Pastor SANON on an attempted coup.” The note was dated June 10.

The alleged attackers were found in possession of an imposing array of military equipment, including assault rifles, pistols, ammunition, bulletproof vests, communication radios, suitcases, ski masks and tags bearing the “DEA” insignia, as well as vehicles and license plates.

More than 400 bullet casings were found at the entrance of the dead-end leading to the president’s residence — fired after the hit squad disarmed cops in the vicinity of the president’s home as the team made its way up the mountain to his house.

“They claim they didn’t kill the President but found him and his wife already inert on the ground. If so, why did they keep shooting?” Haiti’s National Police said in the report. “The allegations of these respondents are contradictory, completely unsubstantiated, and therefore, they have been proven to be false and untrue.”