I Grew Up Straddling My Family's Religion And The Secular World. Then I Had To Choose.

“Get out!” my usually kind, soft-spoken father instructed as he yanked open the sliding door of our Volkswagen Eurovan. I climbed down onto the dirt and watched as my family drove away, leaving me crying on the side of the I-10.

My dad had just passed out sheet music for the Christian folk hymn “Down to the River to Pray” (he made his own four-part harmony arrangements on his MIDI keyboard in our basement), and I had refused to sing second-soprano.

You see, my parents harbored dreams of becoming a famous Christian family singing group. I, at the angsty age of 17, was threatening to ruin that dream.

For generations, our family belonged to a conservative Christian church where obedience to authority is paramount. If you saw women from my church walking down the street in their long skirts and veils, you’d whisper, “Look, Mennonites!” But we’re not Mennonite. We’re ... Mennonlite? Like, if Mennonite people are Honey Nut Cheerios, we’re Golden Honey O’s ― slightly different ingredients and no name-brand status.

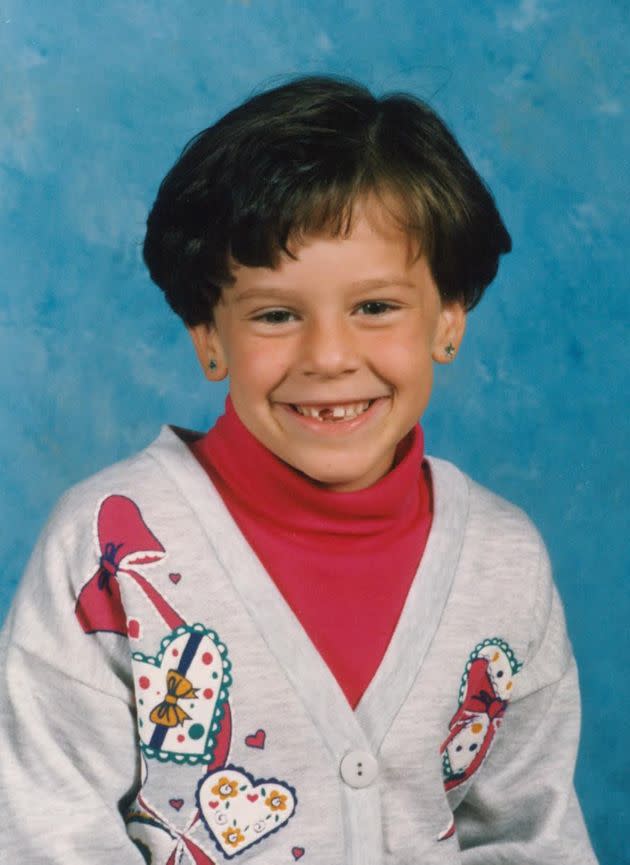

My three younger siblings and I went to public school in Phoenix and navigating between those two very different worlds wasn’t the easiest.

In second grade music class, I had to write down my favorite song. We didn’t listen to secular music at home, so I went with the only song I could think of: “How Great Thou Art.” It’s actually a real banger as far as hymns go.

I mostly kept to myself as evidenced by my preferred recess activity, pogo-sticking. But when I heard that the talent show was coming up later that year, I knew this could be my chance to do something so cool, so unforgettable, I would be popular forever.

My mom had different plans.

At dinner, she announced that we were going to sing a mother-daughter duet.

“That’s so embarrassing!” I said.

“It’s the one thing I’ve ever asked you to do!” my mom said, digging her fork into her Lean Cuisine. It was a lie, but I do think she believed it.

It‘s true they had sacrificed a lot — my hardworking parents showered us with voice and piano lessons, ensuring we had every opportunity to succeed. My mom, a neonatal nurse practitioner who left her job to raise us, spent her days shuttling us from one activity to the next. Still, I knew that singing with her in front of the whole school would be social suicide.

You might be wondering why my school let adults perform in the talent show in the first place. My mom was the PTA president. She was basically the Tony Soprano of the elementary school.

For our performance, she brought a bench from home for us to sit on (“Production value,” she said). We wore matching poofy-sleeved dresses, white hats and white gloves. It wasn’t exactly the style in the ’90s, but you know where it was the style? On “The Lawrence Welk Show.”

My mom was obsessed with Lawrence Welk. She used to watch it every Saturday night while her sister put curlers in her hair for church the next day. My family even stayed at a Lawrence Welk hotel once. Did you know there is a Lawrence Welk hotel? It’s in San Diego!

We performed “Love Makes a Friend Be a Friend Like You” by Christian singer Sandi Patty.

“Why do you always try to be there when I really, really need you there — to care. You’re always willing to share!” we sang to each other against the school’s handmade Hollywood sign backdrop.

My mom did the same exact act with my sister two years later, who managed a much more earnest performance. It’s true what they say: Everyone’s replaceable.

Sixth grade arrived, and I was still struggling to fit in. It was hard enough pretending to be attracted to one of the Backstreet Boys (I chose Kevin to be different), but then my parents announced that our family of six would sing together for the talent show in matching American flag outfits. I begged them to change their minds, or at least their wardrobes, to no avail.

The popular girls lip-synced to “Barbie World” by Aqua, and my longtime crush Joey Vitagliano did a hip-hop dance to “Ghetto Supastar.” We performed a song by the Southern gospel group The Gaithers called “We Have This Moment,” which was ironic because I wanted to be in any other moment but that one.

“Cool song with your family,” Joey Vitagliano said after. His friends laughed.

Once my brother turned 7 and could hold the tenor line, the Christian family singing group started to really take shape. We sang at the Easter sunrise service and my cousin Jenny’s rehearsal dinner in Illinois. We sang “Auld Lang Syne” at the New Year’s Eve program and caroled to neighbors standing awkwardly in their doorways on Christmas.

“It’s the one thing I’ve ever asked you to do,” my mom would sigh when I protested.

The discord between the person I wanted to present at school and the person I was at home crescendoed as the time neared for me to join The Church. As evangelicals, we get baptized not in infancy but as adults. Once I took that holy bath, though, I wouldn’t be allowed to wear jewelry or shorts, date, or go to prom. So I was holding out.

As long as I didn’t die before prom, I could get baptized after, meaning I could go to the dance and go to heaven. It seemed worth the risk.

If I did happen to get murdered, I figured I could quickly give my life to Jesus right before I took my final breath, narrowly avoiding a one-way ticket to hell. This caused me to become hypervigilant to any and all life-threatening events. Coincidently, this is also when I developed a twitch in my right eye.

That spring, my family took that ill-fated road trip to California. It would have been the perfect time to work on our harmonies. But that day, for the first time, I angrily refused to do what they wanted.

Looking back, getting kicked out of the van was a fitting metaphor: Either you’re one of us and you do what you’re told, or you’re left all alone in the middle of the desert ... to die. It sounds dramatic, but that’s what religion can feel like — life or death. It’s painful.

But pain is part of growing up. Sooner or later, we all get kicked out of the van. It’s how we find our own way. Kids can’t stay kids forever.

My dad eventually turned around and silently collected me from the side of the highway. But we all knew what it meant: The band was breaking up. Our Christian family singing group would never tour churches around the country. We wouldn’t become the next Sandi Patty or The Gaithers. We’d never be on “Lawrence Welk.”

After prom, my parents invited the elder from The Church over so I could begin the process of getting baptized. I hid in my room instead. A part of me wanted to cram in a few more experiences before I gave it all up. These experiences opened my mind to new people, new belief systems, and even love.

While home for Christmas my senior year of college, my mom backed me into the corner of the kitchen. “Are you an atheist?” she asked, in the same fraught way I imagine some parents ask if their child is gay.

“I don’t know,” I said, tears streaming down my face.

“The one thing I ever wanted for you was to join The Church,” she said before retreating to her bedroom.

Disappointing my mom was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. As was leaving behind the one place I ever truly belonged. I spent the following years trying to convince my parents that, even though I wasn’t a Christian, I was still a good person (a Sisyphean task).

My siblings scattered all over the country. Only one of us officially joined The Church, but she left years later for a surprisingly morezealous brand of Christianity. I don’t put labels on what I believe, but I do avoid organized groups that tell me what to wear, who to be friends with, or that they have all the answers. In Los Angeles, that rules out quite a few communities — including SoulCycle.

My parents ultimately chose to love and support their children despite them turning out differently than they had originally hoped. They’ve resorted to performing duets together at church.

“The one thing I ever wanted was for you to be happy,” my mom now says. Maybe she’s not disappointed in me after all.

And me? I’m grateful for the time I had singing with my family.

Richelle Meiss is a writer, actor and comic in Los Angeles. Her latest project was creating “Bachelor the Musical Parody,” which will have its world premiere at The Apollo in Chicago in 2022. Meiss is currently working on a memoir and a live storytelling show. You can learn more about her at richellemeiss.com.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.