Back-to-school can re-trigger grief after COVID. Here's how one camp is helping.

Families are used to seeing children’s summer camps for every interest from basketball to baking. But there’s another one gaining popularity: bereavement camps.

"He was able to just be a kid (at camp)," said Valerie Rosaly, speaking about her 11-year-old son, Derek Rosaly. "Not a kid who lost his dad."

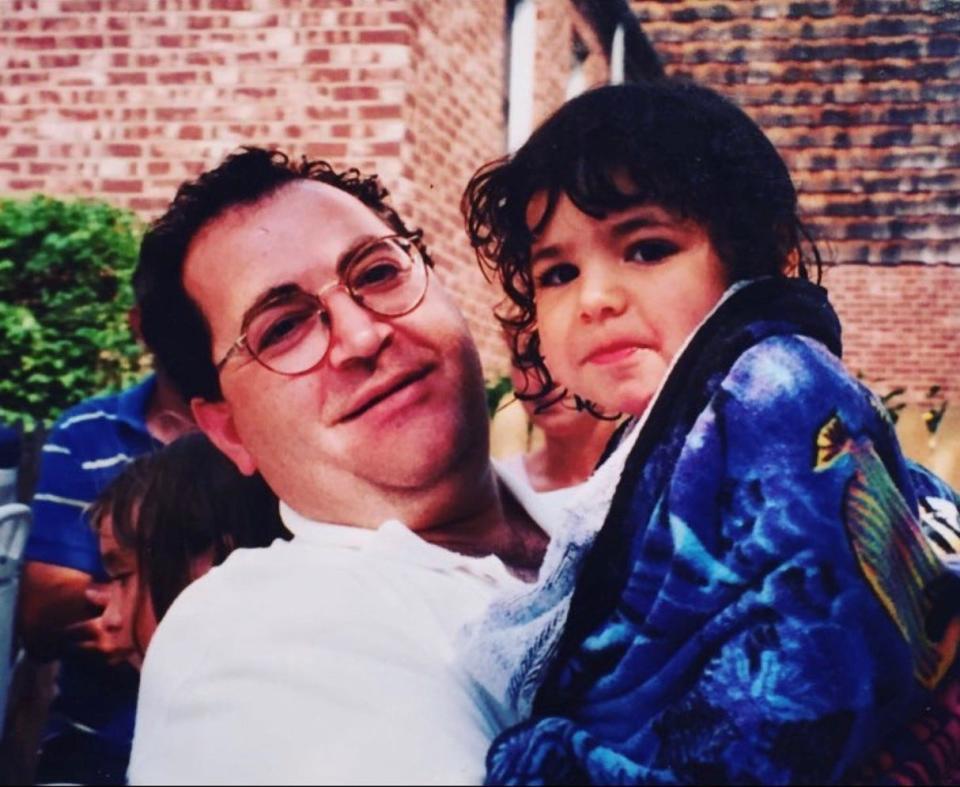

Derek's father, Jay Rosaly, died about two years ago after contracting COVID-19. Valerie says in the immediate aftermath, the loss was unbearable.

"I was just sobbing so, so much because I didn't know what to do and I couldn't believe this happened," said Valerie. "People always want to go back and have questions. The most insensitive question to me, the thing that hurts the most is 'How did it happen?' 'What happened?' 'Did he have an underlying condition?'"

She knew she needed to find a support system and a healthier way for her family to grieve. She decided to try a bereavement camp in her home state of New Jersey.

Camps that help children deal with grief and loss aren’t new. From drug overdoses to suicide, families have been turning to these types of resources for years to help people deal with the pain of losing a loved one at a young age. But now, more kids are having to confront a growing genre of death: traumatic societal tragedies, from school shootings to the pandemic.

“They feel like they're grieving in a fishbowl and that there was always a hush when that topic came up,” says Lynne Hughes, CEO and founder of Comfort Zone Camp. “If they have a death from COVID, there seems to be a lack of understanding or lack of sensitivity for what people are saying to grieving families.”

Hughes says she’s seen an increase over the last few years of kids attending the free bereavement camps she runs in New Jersey, North Carolina and Massachusetts who are dealing with deaths as a result of COVID.

Research suggests more than 200,000 American children have lost a parent or primary caregiver to COVID.

“Going back to school is an obvious reminder of what they lost,” says Hughes. “Starting a new season without their loved ones – and the re-triggering of their loss and their grief.”

It's become so prevalent that her nonprofit’s latest camp – deliberately scheduled for back-to-school rather than a holiday break – is a response to that shift. It’s prioritizing those who have lost parents and siblings to COVID. While she says grieving children tend to find commonalities with each other despite the differences in losses, there’s an additional, more complicated layer when people lose someone in a high-profile event, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

“As soon as they say they have a COVID death, people want to give their opinions about COVID, from masks to vaccinations, and they want to hear the person's story, but almost how it affects them and why a COVID death couldn't happen to them,” says Hughes.

“So whether they're saying, ‘Were they vaccinated?’ ‘What was their stance?' It becomes like a political topic as opposed to, ‘What was their name?’ ‘What were they like?’ ‘What do you miss about them?’ So it's really hard for people dealing with COVID loss to personalize it.”

Derek knows that feeling well. When his father died on December 14, 2020 — the same day the very first deliveries of the COVID-19 vaccine began — he was angry, confused and a little numb. He says he was worried that being forced to talk about his feelings at a camp full of strangers would only make things worse.

"When I entered the camp and noticed how many kids have been through this ... I really, really noticed that I'm not alone," said Derek.

Derek says the camp might sound kind of depressing, but it’s actually the opposite. Kids get to be kids – doing activities like rock climbing and hiking. There's time to explore what they’re feeling as much or as little as they'd like, knowing everyone in the room understands exactly where they’re coming from.

Hughes, who lost her own mother at the age of nine and her father at age 12, says the structure of the camp includes bouts of “mindless fun” alongside more intimate conversations with their peers and volunteer mental health professionals. The idea is to mimic the way children tend to grieve, which can be quite different from how grown-ups approach it.

“Adults tend to grieve around the clock. They almost really can't compartmentalize it. They're just kind of stuck in their grief, 24/7. Kid grief does not look like that at all,” says Hughes. “If you blink, you miss it, but they are grieving. [Children] just grieve in short bursts and they are often able to compartmentalize it and focus on other things.”

Hughes started the first Comfort Zone Camp in 1999 and in November of 2001, geared it toward children who had lost someone in the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York. Since then, the camp has helped children deal with other large-scale tragedies such as the mass shootings at Virginia Tech in 2007 and Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012.

When you lose a parent or sibling in a high-profile event, it can quickly become a dominant narrative that follows you for years afterwards, says Katie Pereira. Her father was an engineer and worked at the World Trade Center.

“I was the kid with the dad who died on 9/11. That's how everybody knew me growing up. And that was definitely, like, my tag going through school,” says Pereira. “For the longest time, it almost bothered me a little bit because to me, yes, that's how my dad died. But he was still my dad. He was still a person.”

Pereira says she participated in the Comfort Zone camp year after year as a child because it helped her cope with her father’s death as an individual loss, rather than shouldering the burden of the collective grief shared by millions when the terror attacks happened.

Pereira and Hughes suggest that if children have lost someone close to them either from COVID or any other event, teachers, caregivers and even peers should take the time to offer comfort if needed. It doesn't have to be the elephant in the room. At the same time, don't be surprised if kids laugh, play and want to behave like normal. It's all part of a child's healing process.

Most importantly, if the loss is the result of a tragedy that's been in the news, it can be tempting to share opinions or ask questions about the event itself. That kind of reaction can be hurtful. Instead, try to focus on who the individual was as a person.

The knowledge and lived experiences of the camp's staff, which now counts Pereira among them, have become assets for parents and educators around the country trying to help students move on from large-scale losses that have received extensive media coverage. But the camp's real triumph is in the kids themselves.

Derek attended his first camp in 2021 and is returning this month. He misses his dad every day, but is learning to cherish his fondest memories and even share them. Like the time they were at the park together with their dog, Kyle. He remembers his dad laughing and lying on the ground surrounded by the Fall leaves with their pup climbing all over him.

"That made me so happy," said Derek with a smile. "Just to know that he was having such a fun time in his life."

His mother says the camp, which also offers counseling for adults, has taught her that she might never fully move on, and that's OK. She can still "move forward." "Wherever we go and whoever we're with, we always have to make the best of it because we're living for Jay, too."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: ‘Grieving in a fishbowl’: How a camp helps kids cope with COVID deaths