Grieving over virus victims may be more common than expected. How each of us can help

If you know someone who’s died this past year of COVID-19, you’re not alone. Not by a long shot.

An article in The New York Times caught my eye, just because of its title, “The Grief Crisis is Coming,” by Allison Gilbert.

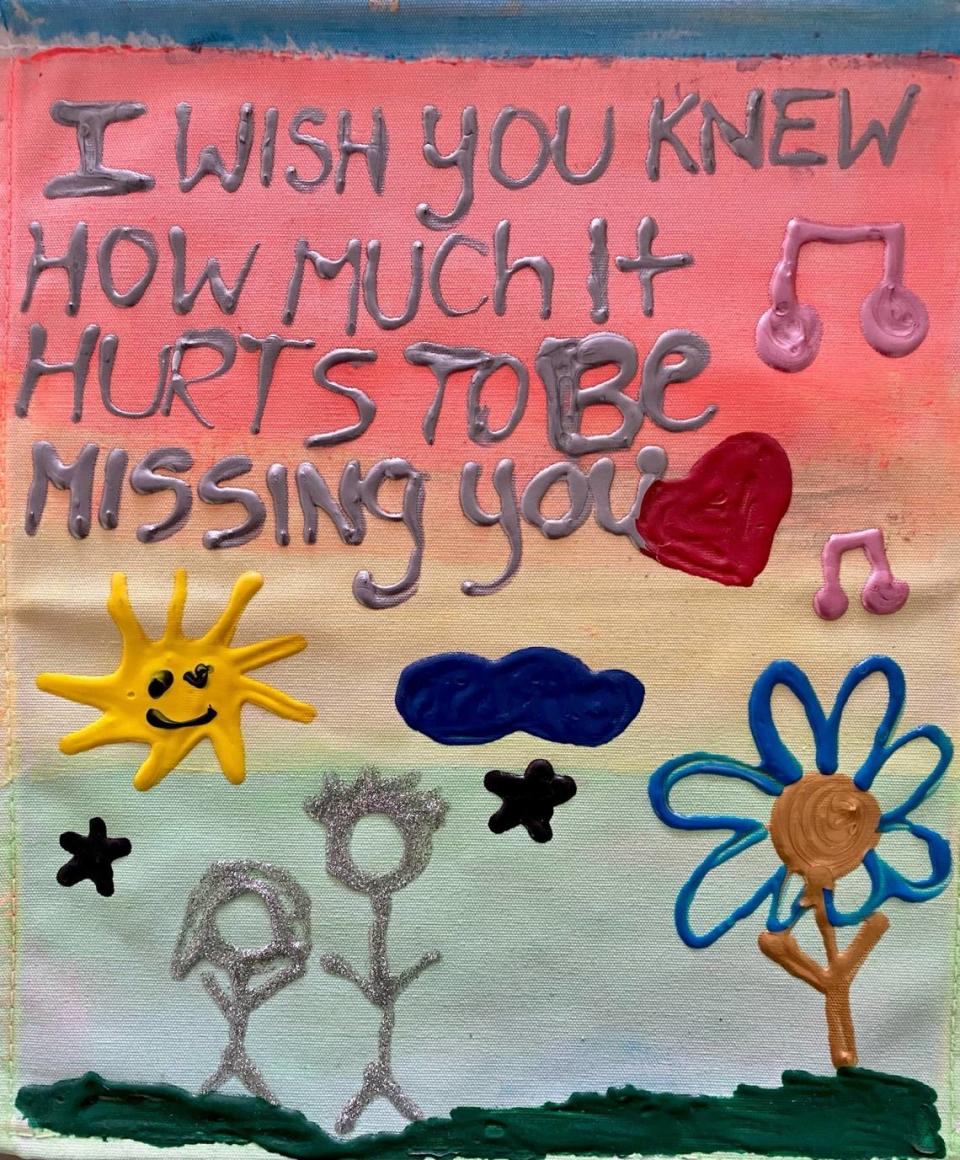

I’ve been saying for the last year that we would eventually face some collective grieving – from the virus, from the isolation, from the strain in families and among friends, and from the events that have happened across the country. Gilbert confirms that such mourning is likely to be more widespread and harder than we had expected, especially when the focus is COVID-19.

She cites a study by a professor at Penn State University that explained what he calls the “COVID-19 Bereavement Multiplier.” He calculates that for every person who dies of COVID-19, nine people who mourn for that person remain behind. These include close family (parents, children, grandparents). But he extended the circle to include aunts and uncles, nephews and nieces. Then, he says that if you widen the circle beyond the immediate group, you could end up with close to 100 people grieving for the one who died.

In our Executive MBA program this past year, we added several sessions as the year progressed to tap into how these executives were managing through the coronavirus pandemic — in particular, how their leadership approaches and the issues they were facing had changed as the pandemic plowed on. The participants shared what their organizations were going through, how they managed, how their employees were reacting, and how the leadership team tried to help them. Pretty standard for questions on how to manage through a crisis.

But in a recent session, I asked them to talk about themselves, what they were going through and how they were managing. Let me tell you, we don’t get into “feelings and vulnerability” in the classroom often, but I found the discussion to be thoughtful and, for many of us in the room, quite meaningful.

I suspect we will continue to talk about leading in crises and make that an ongoing part of the curriculum going forward, rather than waiting to talk about it in the middle of a storm.

The simple and obvious bottom line is that we can help each other if we just open up. We’ll be grieving, yes, but perhaps we can count on support and understanding in ways we’ve never needed to.

Nancy Napier is a Boise State University distinguished professor. nnapier@boisestate.edu. She is co-author of “The Bridge Generation of Vietnam: Spanning Wartime to Boomtime.”