What a Grieving Parent Needs Most

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

When you’re a parent and your child gets hurt or sick, not only do you try to help them get better, but you’re also animated by the general belief that you can help them get better. It might not be the wound-cleaning you personally administer or the medicine you yourself pour into their mouth—you might have to get them to a nurse or a doctor who has the right equipment and skill set—but you believe that it’s you who will get them to the right place, via car or taxi or, God forbid, ambulance, and that once there, you’ll sit by their side or maybe hold them in your lap and they’ll get what they need. Add a little time to mend, heal, rest, and you’ll soon have an exciting story to tell.

That’s not always the case, though. Sometimes, the nurses and the doctors can’t fix what’s wrong. Sometimes, children die. Whatever’s wrong with your child gets worse and they suffer and then they die. After they die, their body begins to decompose and later, it’s zipped into a black bag and taken away by an undertaker in a black van. A few days later, your child is buried in a hole in the ground or cremated in a furnace that incinerates their body into ashes, which you take back to your house and put on a shelf. You wish you could take a kitchen knife and stick it into yourself near one of your shoulders and pull it down and across to the hip on the opposite side of your torso. Then you’d tear apart skin, fat, muscle, and viscera, and pull your child out of you again and kiss them and hold them and try frantically to fix what you couldn’t fix the first time. But that wouldn’t work. So you sit there like a decaying disused train station while freight train after freight train overloaded with pain roars through you.

Maybe one will derail and explode, destroying the station and killing you, and you can go be with your child. Would that be so bad?

Why do I feel compelled to talk about it, to write about it, to disseminate information designed to make people feel something like what I feel? What my wife feels? What my other sons feel? Done properly, it will hurt them. Why do I want to hurt people? (And I do.) Did my son’s death turn me into a monster? That’s certainly possible. It doesn’t sanctify you. Things get broken. Maybe it’s because I write and perform for a living that I can’t help but try to share or communicate the biggest, most seismic event that has happened to me. The truth is, despite the death of my son, I still love people. And I genuinely believe, whether it’s true or not, that if people felt a fraction of what my family felt and still feels, they would know what this life and this world are really about.

Not infrequently, I find myself wanting to ask people I know and like to imagine a specific child of theirs, dead in their arms. If you have more than one child, it’s critical you pick one for this exercise. If you’re reading this, and you have a child, do it now. Imagine them, in your arms. Tubes are coming out of various holes, some of which are natural, some of which were made with a scalpel. There’s mess coming out of some of the tubes. There are smells. The temperature of your child’s body is dropping. No breath, none of the wriggling that seems to be the main activity of kids, no heartbeat. Even just that; imagine searching for your child’s heartbeat and you can’t find one. Their heart will never beat again. It’s not a nightmare you can wake from; defibrillation won’t work. It won’t beat because your child is dead. After a bit, someone will put them in a refrigerated drawer, like you do with celery that turns white and soft when you forget about it. Did you ever make funny horns on their head with shampoo while they were in the bathtub? You will never do that again. Did they ask for help with their shoelaces and their homework? Did you comfort them after a skinned knee? That will never happen again.

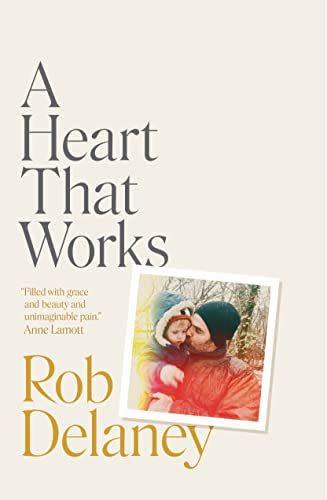

A Heart That Works

amazon.com

amazon.comIt’s unlikely I’ll ever ask anyone to do that face-to-face. Honestly, the idea makes me laugh. Where would we do it? A kitchen, probably. Do I make them tea first? But the point is that I feel the urge. That is one thing grief does to me. It makes me want to make you understand. It makes me want you to understand.

I want you to understand.

But you, statistically, cannot. You forget that my son died. Then you remember. Then you forget again.

I don’t forget. I don’t hanker for much about Victorian times, but the idea of wearing all black following the death of someone you love makes a lot of sense to me. For a while, anyway, I’d have liked you to know, even from across the street or through a telescope, that I am grieving.

Excerpted from A Heart That Works, by Rob Delaney, copyright © 2022. Published with permission from Spiegel & Grau.

You Might Also Like