Grimsby Town boss Michael Jolley opens up on his curious journey as he prepares for Crystal Palace FA Cup tie

“There’s a long version and a short version,” Michael Jolley jokes when asked to describe his career path, and perhaps it’s fortunate that we’ve got plenty of time. It’s a path that has taken him from Sheffield to Grimsby - around 70 miles as the crow flies, but not when you’ve gone via Cambridge University and Crystal Palace, Scotland and the Swedish Allsvenskan. He’s seen the inner workings of Sean Dyche’s Burnley, and been in New York on September 11, 2001.

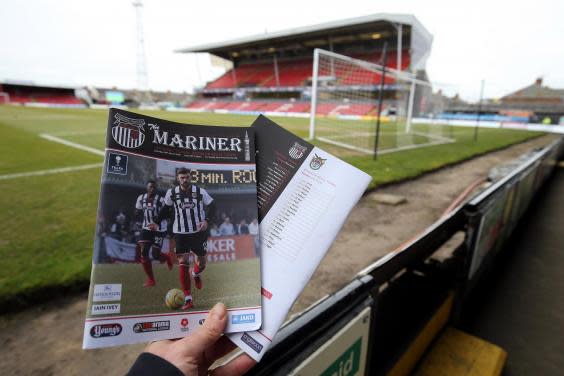

There are times when he still feels like an outsider. Even though he’s been working in the game for almost 15 years, has been steeped in it for as long as he can remember. Even though he’s coming up to a year in charge of Grimsby Town. Even though his side are about to face Crystal Palace in the third round of the FA Cup on Saturday.

He thinks he knows why, too. “Every time I read any match programme, the first thing it says about me is that I didn’t play a game. It’s not everyone’s preferred profile. But as an outsider, you’ve got to find a way. Because if you don’t know what you’re doing, players will soon find you out.”

To the best of his knowledge, Jolley is the first Cambridge graduate to manage a Football League club, although there may have been a few back in Victorian times. He attended Downing College, for people who care about that kind of thing, studying economics. His dissertation was in econometrics: building statistical models for economic systems.

Does any of what he learned back in the mid-1990s help him now, in his current job? “It taught me how to be logical,” he says. “The game’s full of emotions, and it’s easy to get carried away sometimes. But if you can try and keep some perspective and logic in the craziness of football, that can certainly be helpful.”

It certainly helped him get a job as a bond trader at HSBC, first in their London office and then in New York. One bright clear morning in 2001, he looked down from his Bloomberg stock ticker and saw a news flash about a plane hitting the World Trade Centre. “Our office was in Midtown, about two and a half miles north of where everything happened,” he remembers. “It was just a sad, sad time. I had a friend who was lost that day. When you’re having a bad day here at Grimsby, and the skies are grey, that kind of thing pinches you. You remember how lucky we are.”

Jolley came home. Partly, he had been spooked by the attacks and wanted to be closer to his family. But partly, a seed of an idea had already been planted in him. Growing up in Sheffield, football had always in the blood: his father was a director at Stockport County, and Jolley himself was a decent youth player who had been on the books at Barnsley. The idea of coaching had always appealed to him, and so when he returned to London he began volunteering at the Palace academy: trading by day, putting out cones at night.

After three years, he was at a crossroads. Finance paid well, and was a secure existence - at least, in those halcyon pre-crash days. Was he really going to jack it all in for a career that was neither of those things?

“I suppose when you reach a situation like that,” he says, “it becomes about whether you’re willing to take a risk or not.”

So with the blessing of his parents, he started again. After a stint at the Nottingham Forest academy, he moved north of the border, where he took a job at Stirling University while he studied for a diploma in sports coaching. But his time in Scotland came to an end in 2009 when he was sentenced to a year’s probation for having sexual intercourse with a 15-year-old girl. The court concluded - and the Scottish Government later agreed - that Jolley was unaware of the girl’s age, believing her to be 19. “The statement was made at the time about that incident,” he says now, “and I see no reason to elaborate.”

Next came a move to the famous Crewe academy, where he was mentored by the legendary Dario Gradi. Then three years at Burnley, where he rose to the position of Under-23s manager under Dyche. That was the point at which Jolley decided he wanted to take charge of his own club. After successfully applying for the position at AFC Eskilstuna in the Swedish top flight, he returned to the UK at the start of 2018, where he saw off competition from Sol Campbell to be appointed Grimsby Town manager in March.

It was an eye-catching move: “a move away from the classic managerial merry-go-round”, as the club put it at the time. Still, Jolley was bleakly aware that with Grimsby 17th in League Two, an aging squad and a tight budget, his first job in English league management might well turn out to be his last.

One of the first calls he made was to Alan Buckley, the club’s legendary former manager who led the club to three promotions in his three spells at the club. Jolley knew him from his days on the Pro Licence coaching course: as part of a project profiling all the managers who had taken charge of 1000 league games. Buckley remains an occasional visitor to the training ground and a valuable sounding board. And perhaps the biggest lesson Jolley has taken from Buckley is stylistic: from the club’s early 1990s heyday all the way back to the post-war era under Bill Shankly, the best Grimsby teams have always played attractive, high-tempo passing football.

Of course, in order to get there he was going to need to make a few changes. New players were required to overhaul a defence with an average age of well over 30. The club’s medical setup was revamped in an attempt to reduce the number of soft tissue injuries. And then there were the little touches: remarkably, until Jolley’s arrival players didn’t always have their training kit washed for them every day.

The facilities are still a touch basic, and as ever at this level money remains tight. But things are looking up. The club’s Football League status was secured last season, Grimsby are now lodged firmly in mid-table, and now they are in the third round of the FA Cup for only the second time since 2004. A pragmatic rather than dogmatic manager, Jolley has built a sturdy but occasionally adventurous unit, with the potential of Elliot Embleton, the 19-year-old winger on loan from Sunderland, a particular highlight.

Grimsby is a place most popularly associated with the decline of its world-leading fishing industry during the 20th century. But little by little, that reputation is changing, and in a small way, Jolley wants to be a part of it. “Anyone that reads about Grimsby and the region will understand that it’s had its challenges over the years: the fishing industry, all of that,” he says. “But there’s a re-energising, a growth process. There’s a huge wind farm being built offshore, all kinds of things happening. This is a really proud area, and the football club is a very important part of people’s lives. It’s important that we take that role seriously.”

Just as Jolley has taken to Grimsby, Grimsby has taken to him, too. They appreciate the way he has tried to embed himself in the community: putting in a shift in at the ticket office, popping up at local schools, visiting sick or elderly Town fans in hospital. Fans offer to buy him pints when they see him out in town. And despite a Saturday evening kick-off and no train home, 5,500 away tickets have been sold for Saturday’s game at Selhurst Park. “That tells you all you need to know,” Jolley beams. “They’re very passionate people here. They care deeply for their club.”

And so, a final question. Life, as Jolley reminds us, is about choices. Does he ever wonder how things might have turned out had he taken a different choice: had he stayed in the office, trading bonds, accumulating his fortune?

There’s just the faintest hint of a scoff.

“There comes a point where other things in life become important to you,” he explains. “I’m loath to use the word ‘dream’, but if you’ve got something you’re very passionate about, then I believe you should go for it. People often say: look at what else you could have been doing. But there’s nothing I would rather be doing than this.”