The Ground Is Filled with Fire Ice. What Happens If We Pull It All Out?

China has pulled a record amount of clathrate hydrate natural gas from the South China Sea.

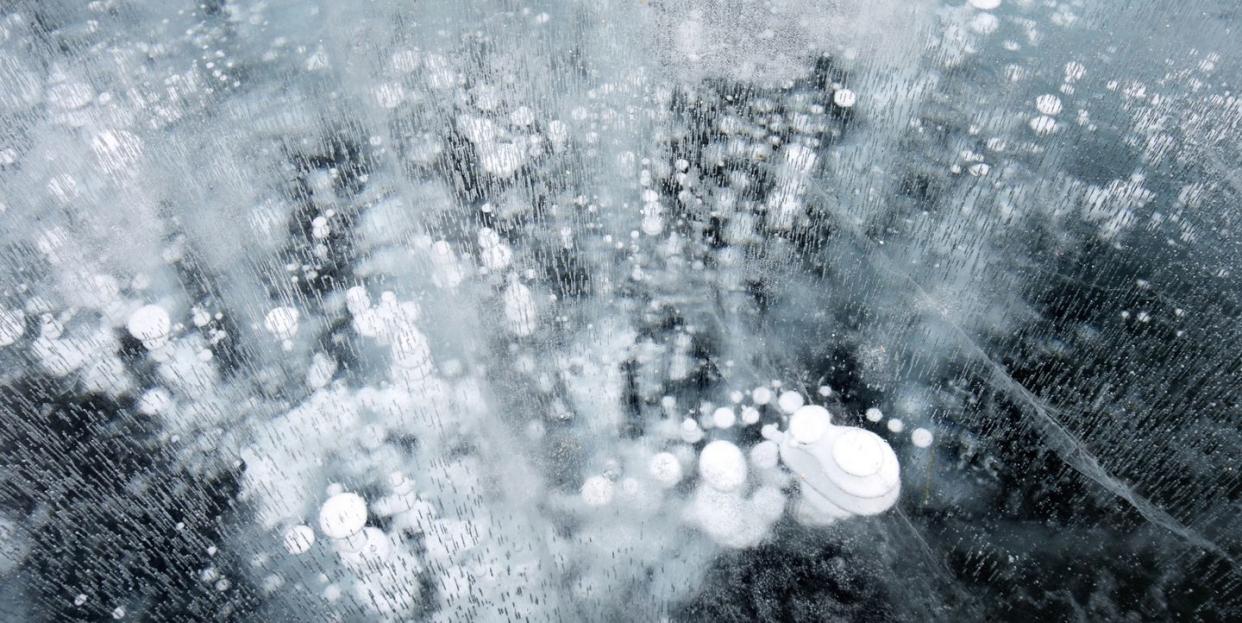

Methane hydrate is the result of specific environmental conditions that make it very hard to mine.

This is just one kind of clathrate, but the family can include many elements and shapes.

China’s natural gas industry has announced a record amount of “fire ice” extracted from the South China Sea. If that sounds like something out of a twisty George R. R. Martin novel, the truth is arguably more intricate.

This coy term refers to methane hydrates, the natural-gas-and-water version of an overall category called clathrates. In a clathrate, one kind of molecule forms a scaffold or lattice that traps another kind of molecule.

In a methane hydrate, ice crystals trap natural gas and hold it basically forever unless something intervenes. Like shale oil, this natural gas is held in place. But if you could cut a cube of oil shale out of the ground, the oil would still be in there. Methane hydrate begins to melt as soon as you move it from its frozen origin place, so extracting it is both financially and environmentally risky.

This is why fire ice is unusual as a product, despite possibly being the most plentiful hydrocarbon on Earth, Oil Price explains. Investors were shy about it before, but now oil prices are “negative,” and experts are concerned about how we'll responsibly expose of the existing pipeline of oil if need be. For China to take big public steps to add even more supply is an interesting decision. But it could also mean energy independence for the country—and even during a global lockdown, the most populous nation on Earth has needs.

For now, let’s focus on how clathrates form, and how they really work in nature.

The vast majority of naturally occurring clathrates are methane hydrates, like those found in the South China Sea. Sometimes, methane hydrates have formed in manmade situ and caused complications. London South Bank University water scientist Martin Chaplin explains:

“Clathrates are notable due to their hazardous formation in natural gas pipeline blockages, their occasional hazardous release of large volumes of gas from underwater natural reservoirs, their potential for the production of natural gas from deep-sea sources and their potential in the removal of the global-warming gas, carbon dioxide.”

A surprising 2016 paper suggested that clathrate structure could be the answer to a food science question: How can we carbonate solid foods in a way similar to soda or champagne? “Clathrate hydrate can store large amount of gas molecules. For example, CO₂ concentration in clathrate hydrate is 20–50 times higher than that in carbonated water. Then, clathrate hydrate has a great potential for the solid carbonated food.”

With that in mind, scientists studied which sugars best supported the generation of clathrate hydrate for use in a dessert. Studying sugar is a tough job, but someone’s gotta do it.

“China was the first country in the world to exploit gas hydrates using a horizontal well-drilling technique,” says China’s Ministry of Natural Resources, via the Chinese state press. The technology could represent a way forward for gas lines clogged by clathrates, even if demand for natural gas doesn’t require further commercialization of undersea gas hydrates in the near future.

More development in the field could also mean technical leaps forward in the realm of trapping CO₂.

H/T: Oil Price

You Might Also Like