This group at Brown University is studying ways to avoid pandemic shutdowns. Here's how.

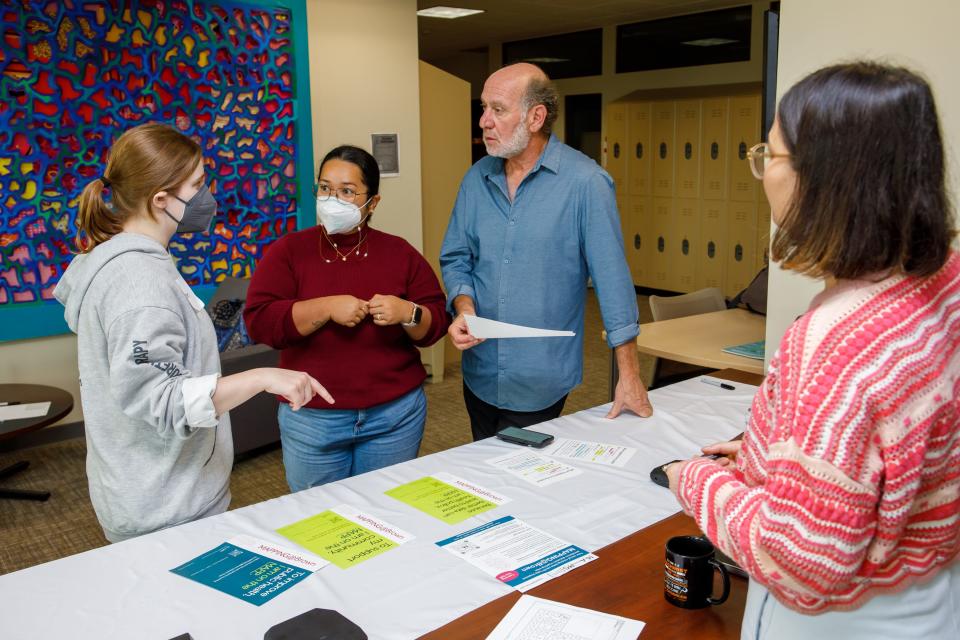

PROVIDENCE – For the last two weeks, the Brown University School of Public Health has been tracking movements in the building, not as "Big Brother," but as researchers trying to mitigate the next pandemic.

It's part of a project under the Center for Mobility Analysis for Pandemic Prevention Strategies, or MAPPS, as it's more commonly called. The idea is to see where in the school people congregate, interact and, theoretically, share germs.

How did the study work?

Participation in the fact-finding mission was voluntary. It worked like this: Volunteers downloaded a Brown-developed app on their phones, researchers installed Bluetooth beacons around the school, and participants' phones connected to those beacons when they were within range of the structures. Once connected, researchers could see how strong the signal was and how long it lasted, allowing them to figure out when people mingled in a particular place and for what length of time. Similarly, the app used Wi-Fi for the same purpose.

Those participating maintain their privacy, as their names are not used in the data.

What comes next?

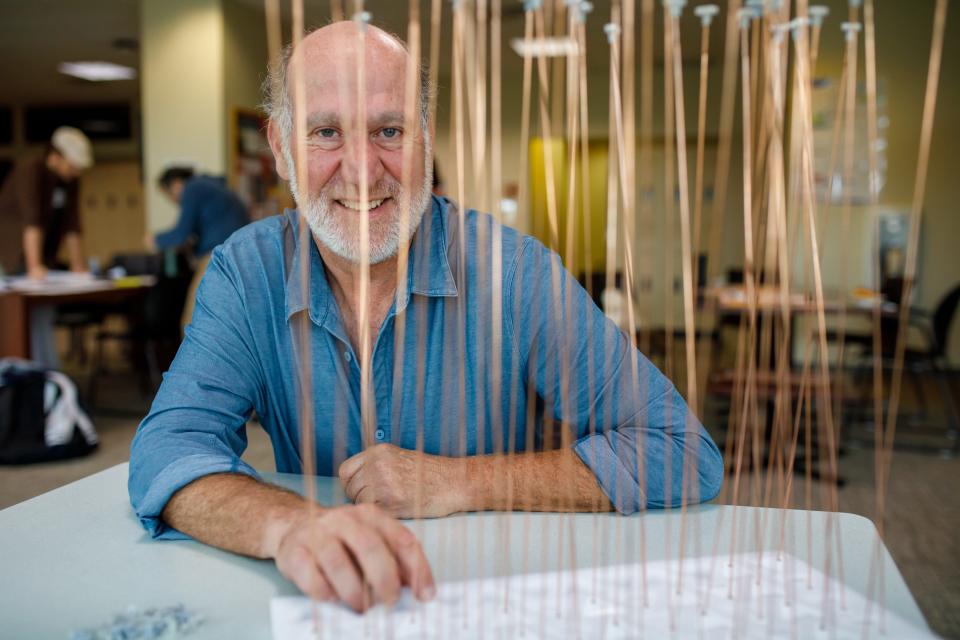

MAPPS director Mark Lurie said the next step is to translate the data to figure out how people tend to move around. Using that information, MAPPS will make recommendations on how to better handle the spread of infection in the next pandemic.

"It’s a way to think about how to make more nuanced decisions about how we move around and how we interact with people, so instead of shutting everything down … we’re hopefully able to make more nuanced and informed decisions based on a pathogen that may emerge," Lurie, a professor in the Department of Epidemiology, said.

Data may help researchers figure out how to avoid shutdowns in future

The point, in part, is a more proactive approach. Throughout the COVID-19 crisis, contact tracing was a tool to identify every person with whom an infected individual had interacted. But that required remembering things like everyone you spoke to, hugged or shared a drink with.

"That kind of recall data is really what we’ve been relying on for a long time in public health," Lurie said.

Now, MAPPS is attempting to figure out strategies to mitigate the spread in the first place, such as one-way staircases or leaving the cafeteria open all day instead of for a four-hour window, thus discouraging people from gathering too closely. That type of thinking isn't new when it comes to pandemic response, but the Brown group believes the thinking next time could be more strategic.

"It would be about what kinds of decisions could we make that would allow us to interact more smartly, such that given the nature of a new pathogen, we would not encourage new transmission," Lurie said.

Eventually, MAPPS will move on to analyzing congregate-care settings, too.

Experts say next pandemic probably isn't a matter of if, but when

Lifespan is taking a similar approach, looking for ways it may be able to ease up on strict limitations in the future.

Kerry Blanchard, Lifespan's director of infection control, who helps establish those protocols, reflected on the hospital system's initial response to COVID-19.

"Back then, we shut a lot down, including units. … We’re trying to change our protocols and policies to be less restrictive, to promote healing, our staff safety," Blanchard said.

Blanchard can't predict when the next pandemic may occur, but recalled the health care industry's past concern about Mpox – formerly known as monkeypox – and said its attention has shifted to Candida auris, a deadly and drug-resistant fungus that can easily spread in health care facilities.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, C. auris, as it's called, was only discovered in 2009, but has since "been reported in dozens of countries, including the United States."

In March 2023, as reported by The New York Times, the CDC warned that the fungus spread during the pandemic at an "alarming rate."

Lurie said experts are also eyeing Ebola outbreaks and cholera infections – "things we thought to be close to eradicated."

"There’s a lot of potential in the coming years, certainly in the next generation, for an event not dissimilar to what we’ve experienced," Lurie said.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: COVID shutdowns were disruptive. Brown research seeks to prevent them