This group helps Miamians transition from public housing. ‘I don’t feel by myself anymore.’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Annette Paul stood in the back patio doorway of her new Boca Raton home, smiling at her accomplishments over the past year and a half.

Just 18 months ago, Paul was alarmed to learn that she and the other 197 tenants of Brownsville’s Annie Coleman 14 would have to move as the public housing project shut down. The notice seemingly came out of nowhere — just as school was starting for four of her five children.

According to Miami-Dade Public Housing and Community Development, rising crime rates and the housing project’s deteriorating condition — all issues that had existed for quite some time, Paul says — made it uninhabitable. The site will undergo a much-needed facelift that housing director Michael Liu estimates will take three to five years. When it is completed, every resident will be guaranteed a place to stay — that is, if they want it.

Sure, Annie Coleman 14 had its problems — like the time when Paul couldn’t even open her front door because of the sewage flowing through the street. Still, the abruptness left her stressed.

“I felt like I was being kicked out with no consideration — like we didn’t mean anything,” Paul, 39, recalled. Eventually, some residents were allowed to stay as long as a year.

For Paul, the ouster became a liberation of sorts. Deciding to raise her kids outside of Dade, she took her federal Section 8 housing assistance voucher and settled in Palm Beach County.

Others stayed in Miami-Dade — but struggled.

Unhappy with the county’s approach, Rose Adams, the Annie Coleman 14 resident council president, refused to accept the voucher. She was one of the last to leave her old home after thieves stole the copper wire at the crumbling site, interrupting power. Adams now lives in North Dade.

Tammy Wesby, 53, and her grandson barely had Christmas that year. Or the next.

“Everything was packed,” Wesby said. In September 2020, she took the voucher to Wynwood — only to discover mold. The county moved her and her now 10-year-old grandson into a modest hotel for about a month while her new Wynwood home was being repaired.

“He had his gifts and everything... but it had made me get a little bit depressed,” she said.

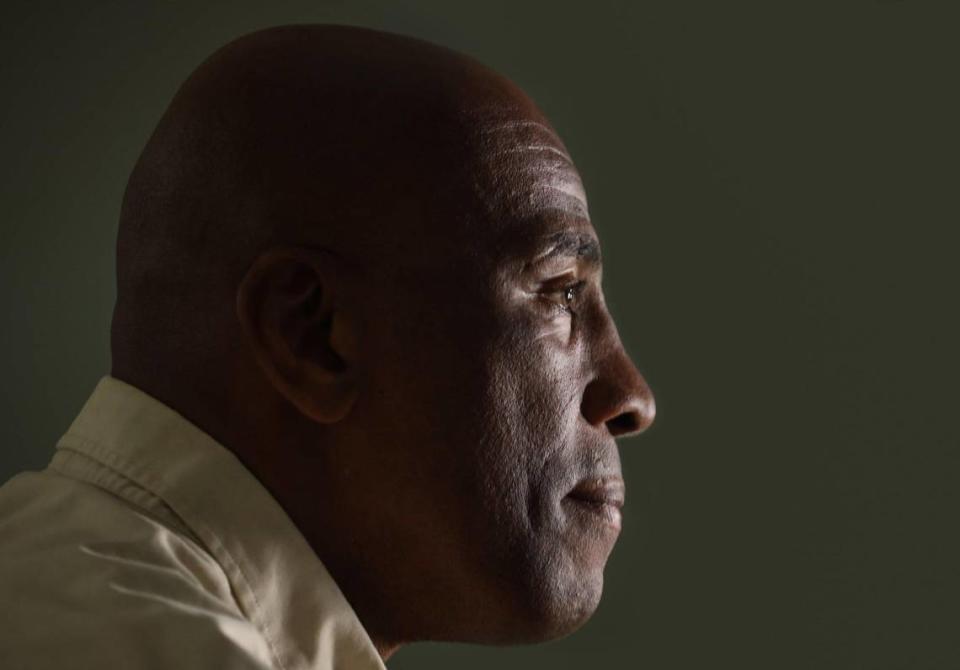

That mental health component was something Lyle Muhammad figured the county didn’t take into account. Not having a car and a lack of experience with landlords were issues too, he knew. As the executive director of the Circle of Brotherhood, a local community service organization, he also knew that residents weren’t prepared for such a transition.

So Muhammad and the COB set out to help. Through conversations with residents and PHCD, they created the Annie Coleman 14 relocation program, a year-long initiative that included a two-week crash course on topics including tenants rights and mental health, followed by 12 months of on-call assistance. Whenever a problem arises, graduates can contact their case managers, who will help however possible.

“We wanted to fill the gaps to support the residents in their relocation, stabilization and elevation,” Muhammad said.

The program goes beyond the immediate transition, said immediate past Miami-Dade NAACP chapter president Ruban Roberts. It seeks to equip each individual with the resources to better themselves, both mentally and economically.

“Folks who have not lived in [public housing], haven’t experienced those situations or do not belong in the same cultural group don’t always have a good understanding about how to deal, cope and overcome these challenges,” Roberts said.

“You want to make sure that you give them the tools not just to sustain and survive but to break the cycle of poverty.”

‘You left these cities to drown’

The plight of the displaced Annie Coleman residents underscores a fundamental failure of many public housing communities.

When the concept first emerged in the late 1930s, it was thought of as righting a wrong for the good of the nation. Housing, so the thinking went, was a human right that the federal government should ensure. With the country still in the midst of the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt believed public housing would provide opportunities for both sheltering and employing low-income people.

“I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished,” Roosevelt declared at his second inaugural address in 1937. “The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.”

Robert Weaver, an economist and one of the biggest proponents of public housing at that time, saw the importance of shelter as a way to advance poorer communities as a whole.

“The whole theory behind public housing is that the individual is affected greatly by his environment,” he wrote in 1938. “Not only does the person develop more fully if he is given better surroundings, but society benefits because a better citizen is produced.”

In Miami and cities like Chicago and New York, these ideals didn’t always translate. Graceless two- and three-story “concrete monsters,” as they came to be known, were built in racially segregated neighborhoods like Liberty City and Brownsville. Over time, these federally and locally run housing programs began receiving less and less funding, leaving the developments dilapidated. Then, as urban living became undesirable — afflicted in the ‘70s and ‘80s by inner-city flight and rising crime and poverty rates — public housing shouldered the consequences.

“You left these cities to drown,” said Derrick Scott, a lecturer at Florida International University’s global and socio-cultural studies. “What’s left is Black people who couldn’t afford to move out.”

Many of those who remained find themselves in units that, more often than not, lack basics. In 2010, the Department of Housing and Urban Development authorized a study that discovered $26 billion in deferred repairs nationwide — a figure that has likely doubled, the New York Times reported in 2018. Housing advocates estimate that more than 10,000 units are lost each year due to the lack of upkeep.

Miami-Dade County itself has reported $500 million worth of backlogged maintenance for its roughly 9,500 units, according to Liu. Annually, the department — which already runs on a deficit of about $10 million — spends anywhere from $10-14 million on capital improvements.

“The economics of public housing in the United States are not good,” Liu said.

That’s essentially how Annie Coleman 14 wound up in its current state. Built in 1967, the 245-unit project battled issues with mold, mice and crime prior to its closure. In Sept. 2019, after declaring the residence uninhabitable, each of 198 residents were told they had to leave and were given Section 8 vouchers. The residents would also be guaranteed a spot in the improved Annie Coleman whenever it reopened.

Although Miami-Dade would cover moving expenses, security deposits and utility hookups, there was a need for a counseling service outside of what the county would provide.

Enter the COB, a local grassroots organization whose activities have included hunger strikes protesting violence and advocating for voting rights restoration for felons. Following months of advocating for Annie Coleman residents at city commission meetings, COB received funding from the county for the COB’s relocation program. In addition to transforming the way residents approached their day-to-day lives, the program seeks to help them create a pathway to home ownership — a key element for people like Constance Fleming.

Born and raised in Liberty City, Fleming lived in Annie Coleman for 41 years. There, the 59-year-old raised three children alone; two are now college graduates. The county never reached out to her about a pathway for home ownership, she said. Initiatives like the Family Self-Sufficiency Program, which is designed to help families increase their savings and reduce their dependence on government assistance, apply only to those in Miami-Dade’s Section 8 Home Choice Voucher program, not residents of public housing, said Liu. The reasoning? Lack of funding.

“I could’ve been paid for a house,” said Fleming. “… We never get those opportunities.”

The relocation program, however, offered Fleming a second chance. By learning about both the history of public housing and the importance of mental health, she was able to identify issues that have run through her family for generations.

Past government practices created “a lot of social conditioning,” said Roberts, who taught the former Coleman residents about the correlation between mental health and wellness. “When you’re in that bottom rung, you get a feeling that you can’t achieve, this is your place: it’s almost as if there’s a caste system.”

One of Roberts’ most popular exercises asked residents to break down the first 21 years of their lives into seven year increments. The theory, as taught by Roberts, was that certain needs had to be met at each stage. If not, the individual likely suffered some form of trauma that will continue to cripple them, their families and even the community unless properly addressed.

That awareness transformed Paul’s perspective, she said. In her six years at Annie Coleman, she often asked herself why: Why didn’t her neighbors care about where they lived? Why didn’t they have consideration for others? Why do poverty and crime appear linked? Hearing the perspectives of her neighbors allowed her to find commonalities in their experiences.

Paul herself had dealt with a mother who she says called her a disappointment. A maintenance contractor, she sometimes cleaned toilets to put food on the table, something her mother thought was unbecoming given that Paul graduated high school and even briefly attended Miami-Dade College.

“They’re no different from me,” Paul said. “I see that we all experience trauma, we all have unresolved issues… It makes sense now that in order to have community, we have to have healed people.”

In Paul’s world, healing required acceptance — that no matter how hard she works at her job and with her children, a painful rift with her own mother might never mend.

Her kids, Paul said, were her ultimate motivation: “If I better myself, it’ll influence my kids and the people around me in a more positive way.”

Paul’s realization hints at an issue that Han Li, an associate professor in the University of Miami’s Department of Geography and Regional Studies, has long since heard in urban planning circles. When it comes to saving minority neighborhoods, the solutions often involve boosting residents’ self-esteem and creating pathways for upward mobility. These ideas, however, are rarely implemented, according to Li.

“The ultimate purpose of public housing and affordable housing policies is to lift people out of poverty,” Li said. “… Maybe this program can be the example.”

‘I don’t feel by myself anymore’

On a recent Thursday, Paul strolled confidently to the front of the room, stylishly dressed in a leopard-print blouse with a black hair wrap tied around her head. For the previous two weeks, she’s made the hour-long journey from Boca to Brownsville, never missing a class. Her dedication has led to an invitation to speak at the program’s graduation ceremony.

Her face was all business — stern, calm and without emotion — as she turned to face the audience. Then the tears came.

“I’m just grateful that I can stand here despite the challenges, despite even my mom, that I’ll be all right,” Paul told the crowd of 50 or so friends and family members who came to support the relocation program’s first graduating class.

Though her mother didn’t attend, the other guests gave Paul strength. Beaming grins and optimistic faces cheered her on. Plus, her family had grown just a bit.

“We want to be an example for the people who will be behind us so that they can understand that even if someone puts them down, they have a family that will bring them back up,” Paul said in her graduation speech.

Of course Paul’s journey is far from over. Now, a little over seven months after her move, Paul is learning to work with her white neighbors. She’s just started a job cleaning a women’s clinic. And she now has a yard and pool to care for — amenities not found in public housing. But with a support system in her corner, she feels more empowered than ever.

“I don’t feel by myself anymore,” she said.