Group calls for Castleman statue's return - and a new Louisville monument

A group is calling for the return of the controversial John B. Castleman statue to the Cherokee Triangle neighborhood − across from a proposed memorial honoring Black leaders who fought against the segregation of Louisville parks.

Castleman, a former Confederate officer who later helped plan the city's parks, "made Louisville a better place to live for all residents. And I mean all residents, race, culture, whatever," architect Steve Wiser, a spokesman for Friends for Louisville Public Art, said during a press conference Wednesday at the statue's former location.

He called on Mayor Craig Greenberg to re-examine the statue's removal and for the city to pay for the new monument honoring Black parks leaders.

But Greenberg spokesman Kevin Trager told The Courier Journal later Wednesday that the city "has no plans to place the Castleman statue back in its original location nor any interest in doing so."

"On July 20th, we will participate in a community facility review before the landmarks and planning commissions where we will explain our decision," Trager said. "As we begin to look at new options for that site we will be soliciting public input in the coming months.”

The group's proposed memorial would include several Black leaders who fought against Jim Crow laws that segregated Louisville parks systems, according to a press release from the Friends of Louisville Public Art.

These leaders include:

Dr. James Bond, the YMCA service director at Camp Taylor during World War I who facilitated a compromise that established Chickasaw Park for Black residents during segregation.

I. Willis Cole, the founder of the Louisville Leader, a Black newspaper that was published weekly for 33 years, who fought to prevent the segregation of Louisville’s streetcars and worked to keep the city’s parks desegregated.

Harvey C. Russell Sr., the dean of Kentucky State College (now Kentucky State University) and president of West Kentucky Industrial College (now West Kentucky Community and Technical College) for whom the Russell neighborhood is named.

William Warley, the founder of Louisville News and president of the Louisville NAACP chapter who fought for African Americans' right to vote.

Mona Carroll, who was told to leave Cherokee Park when she attempted to fish in Willow Pond and became a part of the NAACP suit in Jefferson Circuit Court to end segregation in the parks.

Dr. Pruitt Owsley Sweeney, a president of Louisville NAACP and a chairman for the Louisville Urban League who sued the city for operating a segregated public golf course.

The Mayor's Office has not commented on the newly proposed monument.

The arts group's proposal comes after the Kentucky Supreme Court reversed a lower court ruling that allowed Louisville Metro Government to take down the Castleman statue and place it in storage. The high court's 6-1 decision ruled the city violated due process in getting approval to take the monument down.

There was an inherent conflict of interest in the process, the court said, because three of the people who voted to approve the removal were employees – one on the Cherokee Triangle Architectural Review Committee and two on the Historic Landmarks and Preservation Districts Commission.

Castleman, who also was a brigadier general in the U.S. Army during the Spanish-American War, has drawn both harsh criticisms and praise from the Louisville community. Backers of the monument said Castleman served for the U.S. Army for far longer than the Confederacy and that he helped keep Louisville's parks integrated during his lifetime.

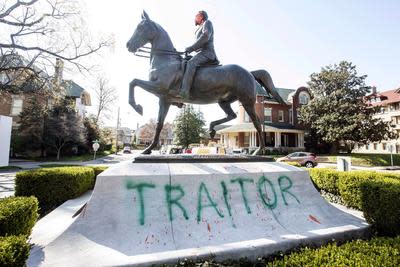

He did help create Louisville's parks. He is not depicted in Confederate uniform on the 15-foot bronze statue, in which he sits atop his prized horse, Caroline.

The statue was removed in June 2020, when Louisville also saw racial justice protests following the police killing of Breonna Taylor. Then-Mayor Greg Fischer called the statue a symbol of the "horrific and brutal slavery of men, women and children."

More: A timeline of how the John Castleman statue went from revered to reviled to removed

Reach Eleanor McCrary at EMcCrary@courier-journal.com.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Arts group calls for Castleman statue's return to Cherokee Triangle