Growing Kosovo: Iowa helps build a nation from the ashes of war

VUSHTRRI, Kosovo — Sipping macchiatos in the shadow of a Byzantine-era castle, Xhafer Tahiri recalls memories from 20 years ago as quickly and precisely as the names of his children.

March 24, 1999, was the day NATO forces’ bombs lit up the Kosovo horizon, bringing Tahiri hope that the injustices he and his fellow Albanians suffered at the hands of the Serbians might be over.

April 15, 1999. The night that fighting between Serbian and NATO forces arrived on his doorstep, forcing the 15-year-old and his eight siblings to leave their home with only what they could carry.

June 15, 1999. The morning his family returned to their village of Vushtrri to discover a patch of scorched earth and a few bent and broken walls where their home once stood.

Then there's Aug. 13, 2018, when, as mayor of his hometown, Tahiri walked the Iowa State Fair’s Grand Concourse, threw out the first pitch at an Iowa Cubs game and watched the flag of Kosovo — Europe's youngest democracy — rise outside the City Hall of Norwalk, Vushtrri's sister city.

Talk of pork chops on sticks and Big Boars might seem wholly out of place in this traditionally Muslim country half a world away from Iowa, but Tahiri is far from alone in his reverence for the Hawkeye State.

For years, Iowans in and out of military fatigues have quietly worked to lift this tiny country out of chaos and poverty spawned by years of bloody conflict and a campaign of ethnic cleansing.

They are, in many regards, literally helping grow a new nation — and putting Iowa on the front lines of foreign diplomacy in the process.

In more than 20 trips annually, members of the Iowa National Guard along with civilian partners instill American interests in the Balkans — a strategic foothold in the shadow of Russia that has for much of the modern era been the political powder keg that lit the world on fire.

For Iowa, the relationship — which marks the first time a U.S. state has formed both a security and civil partnership with an entire country — is not simply a feel-good venture, said Lt. Col. Michael Wunn, former director of the Iowa-Kosovo partnership.

From establishing the first foreign consulate in Iowa to cultivating new revenue opportunities to training a burgeoning military, Kosovo has opened almost as many doors for Iowans as Iowa has for Kosovars.

"It's good for America to have a friend in the Balkans for the same reason it’s good for America to be in Korea,” said Mark Baskin, a former civil servant with the area’s U.N. peacekeeping mission. “If the state of Iowa is carrying forward the interests of the United States in this region, it’s playing a very significant role — even if it’s not the center of attention in the news.”

In the 10 years since Kosovo declared independence, it endures as an example of American intervention that worked. Yet, the nation is at a tipping point.

Key members of the U.N. Security Council, including Russia and China, have refused to recognize Kosovo's independence, and the country hasn’t met requirements to join the European Union or NATO.

Kosovo’s inability to stabilize Serbian relations has led to shaky security and an unemployment rate of more than 30 percent.

But with roughly half of the population under age 25, a growing group of young Kosovars is pushing to fight corruption, fix the justice system and stem Islamic extremism.

"People here are resilient because they've lived through very difficult times," said Baskin, who now teaches at Rochester Institute of Technology’s Kosovo campus.

"I have friends here who have seen seven or eight members of their family killed during the war, and yet they're OK. They’re moving forward."

As the young country continues to fight for change and embrace optimism, Kosovo's future is one that Iowa is helping shape.

In a nightmare, dreaming of freedom

By May 2, 1999, Tahiri’s 11-person family was living in a "2-square meter" nylon tent just inside the Kosovo Liberation Army's lines.

Every day, they split their meager rations. Every night, Tahiri fell asleep to the sound of explosions over his rumbling tummy.

"If I close my eyes, I’m back there immediately," he said. "And the worst part was the fact that we never knew if we are going to make it through alive."

On that particularly gray spring day in his hometown, more than 100 villagers trying to evade Serbian forces were instead massacred in a field just outside city limits. Videos of the aftermath show their belongings strewn across the pasture, each hastily dropped as the villagers tried to outrun Serbian bullets.

Villagers were buried where they fell, which today is a grazing area for cows.

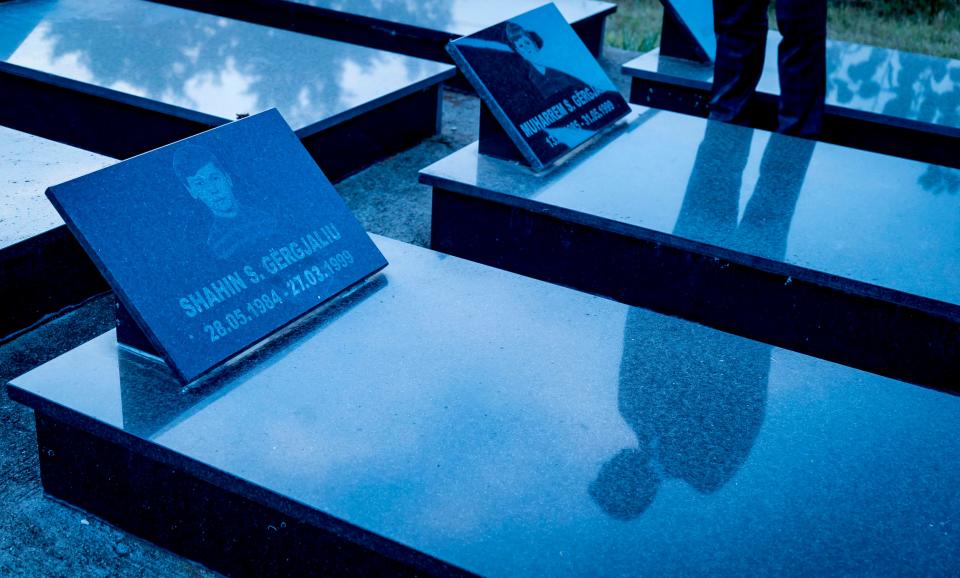

This graveyard — where the headstones have been replaced with a uniform black granite — is emblematic of the dichotomous way the war is both remembered and forgotten.

All across the country, markers and memorials sit in the center of towns, on roadsides or in fields, but life in this modernizing country evolves around them.

Although people embrace two religions — most Serbians are Orthodox Christians and most Albanian Kosovars are Muslim — the Kosovo War was a conflict over ethnicity.

Before it achieved independence, Kosovo was a Serbian province. Under the reign of strongman Slobodan Milosevic, the minority Serb group lorded power over the majority Albanians.

As disdain between the two groups intensified, Milosevic fired Albanian-speaking men from state jobs, shut down Albanian media and declared teachers would instruct in Serbian exclusively.

By the mid-'90s, which tongue you spoke determined whether you were a second-class citizen, said Jehona Gjurgjeala, an educator and activist who was 15 when the conflict ignited.

"You go into this mode of self-preservation where you know what you can and you can't do," she said. "And you kind of kept yourself safe by actually limiting your movement and limiting your behaviors so that you didn’t provoke bad reactions.”

On RIT's campus in Kosovo, students who were babies during the war understand the conflict through their elders.

"(My parents) tried not to let the war get in our ears because we were still very, very small and they didn’t want us to have trauma," said Gelonida Bajraktari, 20, a public policy and international relations major. "But I still remember as young children that they wouldn’t let us play on the streets. … They would always keep us inside, but never telling us why."

Gjurgjeala and Tahiri, like many in the generation who were teenagers during the conflict, returned to Kosovo to help form the country their friends died to create.

Gjurgjeala went to school in London and worked as an executive at Expedia before deciding that in the one life she had to live, she "wanted to leave something behind."

Tahiri studied in Italy, went to law school and joined the team drafting Kosovo's declaration of independence, which used the U.S. Constitution as a framework.

Even a decade later, Tahiri's tears come quickly as he talks about being in parliament's hall when the document was signed.

"That night, I went back home and kissed my father and my mother and said, 'Congratulations,'" Tahiri remembered. "They raised a family of nine children in a system where they didn’t know which one of us will survive because we didn't have freedom. Yet it didn’t stop them."

Signs of Iowa influence abound

On Feb. 5, 2005, Lt. Col. Wunn flew into Pristina en route to join other Iowans already in Kosovo on a peacekeeping mission. From thousands of feet up, what few roofs that survived the war barely peaked out over a blanket of white snow.

"You could see places that had been bombed," he said. "You could see places where people had been displaced. There was still a need to clean up and to repair and re-establish."

More than a decade later, the trappings of normal European life abound in Pristina. Coffee shops bustle with students and suited business people, and rebuilt town squares feature ornate public art.

But unlike Paris or Bucharest, a Disney-esque love for America is woven into the city’s fabric — a nod to the help the U.S. provided in fighting the Serbs.

Bill Klinton (sic) Boulevard, the main drag through town, is in a perpetual traffic jam. Hillary, a store at the corner of Klinton Boulevard and Robert Doll (sic) Street, sells reproductions of the former first lady’s most famous ensembles.

Elsewhere, roads named for George W. Bush and Woodrow Wilson (who championed self-determination for nations) wind around construction on glitzy new apartments and office buildings.

The thumbprint of Iowa is evident, too. The state flag hangs alongside those of Kosovo and Albania outside the country’s Ministry of Defense. The prime minister lives on Iova (sic) Street. And an Iowa State University banner hangs in a coveted spot behind the hottest bar in Pristina’s poshest neighborhood.

All this Hawkeye State fanfare was far from Maj. Gen. Tim Orr’s mind when he pushed for the Iowa National Guard to join with the Kosovo Security Force as part of the federal State Partnership Program.

Founded in 1993, the program connects Guard units with less-developed countries to share best practices.

When the Kosovo partnership came up in 2011, Iowa was one of the only states that didn’t have a formal agreement through the program. Competing against 17 other units, Iowa won out because of the Guard’s previous deployment to the area and Iowa’s connection to agriculture, which leaders thought could benefit the country’s rural regions.

"It was clear to us, too, that there would be opportunities to engage with Kosovo outside of those military activities," Wunn said.

The Guard reached out to Iowa Sister States to begin the process of creating a civilian connection, but, at the time, the organization couldn’t take on more agreements.

Founded by former Gov. Bob Ray, Iowa Sister States takes its partnerships "quite seriously."

"Unlike perhaps other states that sign them and kind of file them away, we actively engage with our sister states,” said Kim Heidemann, the group’s executive director. “So … we felt we really had to take a good look at the benefits of the relationship.”

Each visit brings 'something concrete'

Meanwhile, Kosovo’s then-president Atifete Jahjaga was on a mission to rebrand her country.

Jahjaga saw expanding the established military partnership into other governmental arenas as crucial to that campaign. So she directed her top ministers to visit Iowa and engage with the state's leadership.

Two years later, in 2013, then-Gov. Terry Branstad made the agreement official when he went to Kosovo to sign an accord connecting the countries.

“I'm very proud (of this relationship) because from every single visit, something concrete comes out that opens the door to the partnership and the work between both of our states,” Jahjaga said.

For Kosovo, the partnership "distills down the U.S. into a manageable organization," Wunn said.

"Rather than New York or Washington, D.C., where they're just a small fish in a big ocean, they can come to Iowa," he said. Here they “have more of that personal connection and access to policymakers, access to business leaders, access to the experts.”

While economic relationships bloomed from the partnership — including a Kosovo vineyard that now sells wine in Iowa — knowledge is what Kosovars desperately want as they prepare to join the greater community of nations.

Responding to that call, Iowa Sister States worked to bring professionals and specialists to the table.

To help with foreign policy, University of Iowa law students worked with diplomats in the Kosovo Ministry of Foreign Affairs. To stitch together an updated educational system, community college students are planning workshops with Kosovar teachers.

And to get youth interested in agriculture, which is widely seen in Kosovo as un-hip, Future Farmers of America exchanged delegations with the country.

In addition to allowing for citizen-to-citizen diplomacy — a key part of all of Iowa Sister States’ relationships — these partnerships offset costs.

Iowa Sister States is allotted $19,000 of state money a year to maintain and grow the Kosovo partnership. The Iowa National Guard doesn’t use any state money, but spends an estimated $300,000 of federal funding annually to conduct about 15 exchanges per year.

"When you look at how much a bomber cost or how much a day of deployment in Afghanistan cost, that’s nothing," Baskin said, "$300,000? I mean, that's paper clips."

Seeing the unimaginable in Iowa

On Dec. 22, just beyond where we sipped macchiatos, Tahiri was sworn in as Vushtrri’s mayor.

In the shadow of the centuries-old castle, Tahiri faced a new beginning. Now, he had the chance to rewrite his hometown’s story of struggle into one of advancement.

Soon he’d find out he had a few partners on that journey — his sister city, Norwalk, and the state of Iowa.

When I arrived in Kosovo, I wanted to find out what Iowa was getting out of this relationship.

Achievements and accolades aside, the real answer doesn’t play well in pamphlets or bar charts.

The real answer is legacy. Here, in this small county with big political and strategic importance, a handful of Iowans are molding what our state’s heritage will be across the world.

“The question you have to ask yourself is, is charitable donation, is helping a neighbor in need, is that worth it?” Lt. Col. James Grimaldi responded when challenged what Iowa really gets from all this.

“You do it because it’s right,” he continued. “The people of Kosovo are eager. They love Americans and they want to move forward and they could use our help.”

The international community will inevitably fade away as Kosovo continues to develop, but Iowa has made a long-term commitment. And that unique dedication will cause real change, Gjurgjeala, the educator and activist, said.

Iowa, she said, "has managed to build something that is literally a massive community … every point of entry multiplies straight away because there's so many stakeholders on both sides."

For Heidemann and the other Iowans at the August flag-raising ceremony outside Norwalk’s City Hall, another successful sister city relationship offers a wonderful return on investment and a good example for local-level connections.

But watching the Kosovo flag sway in the same breeze as the Stars and Stripes was so emotional for Tahiri, he wasn’t sure he’d make it through his speech.

For the boy who escaped war with only what he could carry and helped his family rebuild their lives from a scorched patch of grass, this was another freedom that seemed like a fantasy.

And for the man who watched his country declare independence and who became his hometown’s mayor, it was the moment he realized his future just might be filled with days he once deemed unimaginable.

About the series:

After a bloody campaign of ethnic cleansing and an unsteady path to independence for Kosovo, Iowa has been quietly helping the nation's nascent democracy for more than 20 years. Now, with a foothold in one of the most politically important regions of the world, Iowa is seeing its citizen-led diplomacy pay off.

Iowa Columnist Courtney Crowder and photographer Rodney White hopped a military transport flight with the Iowa National Guard to learn more about this deep relationship. In this three-part series, the pair will explore how Iowa's influence is woven into Kosovo's fabric.

About the authors:

COURTNEY CROWDER, the Register's Iowa Columnist, has visited four of the seven continents and is hoping to convince her fiance to honeymoon in a fifth next year. When not jetting across oceans, she traverses the state's 99 counties telling Iowans' stories. You can contact her at (515) 284-8360 or ccrowder@dmreg.com. Follow her on Twitter @courtneycare.

RODNEY WHITE has been a senior staff photographer at the Register since 2000. He covered the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Super Bowl XL and the Olympic Games in Athens, Greece. He also traveled to Afghanistan, China and, now, Kosovo on assignment covering Iowans worldwide.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Iowa and Kosovo: How Iowa is helping develop a small Balkan nation