Grumet: Democratic election worker says Texas AG 'tried to throw me in jail'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Last July, a friend sent a text message congratulating Rob Icsezen on the grand jury’s decision. “Keep fighting the good fight,” the friend said.

“And I said, ‘What the hell are you talking about?’” Icsezen recalled.

That’s when Icsezen, the Democratic presiding judge of a Harris County elections board, learned the Texas attorney general’s office had just issued a press release about him.

And that the attorney general had just tried to indict him for his work in the 2020 general election.

And that a grand jury in neighboring Montgomery County had declined to charge him with obstruction of a poll watcher, a Class A misdemeanor that could have brought up to a year in jail.

“It was real,” said Icsezen, 44, who is telling his story publicly for the first time. “They very much tried to throw me in jail.”

Underscoring the peril of his status as an election worker in Texas, Icsezen added: “I’m one Montgomery County grand jury away from having been put in handcuffs and dragged to jail in front of my children, and that is devastating to me.”

Icsezen (pronounced ITCH-seh-zen) is a father of four who has practiced law for two decades, most recently for the Democratic Party in Houston.

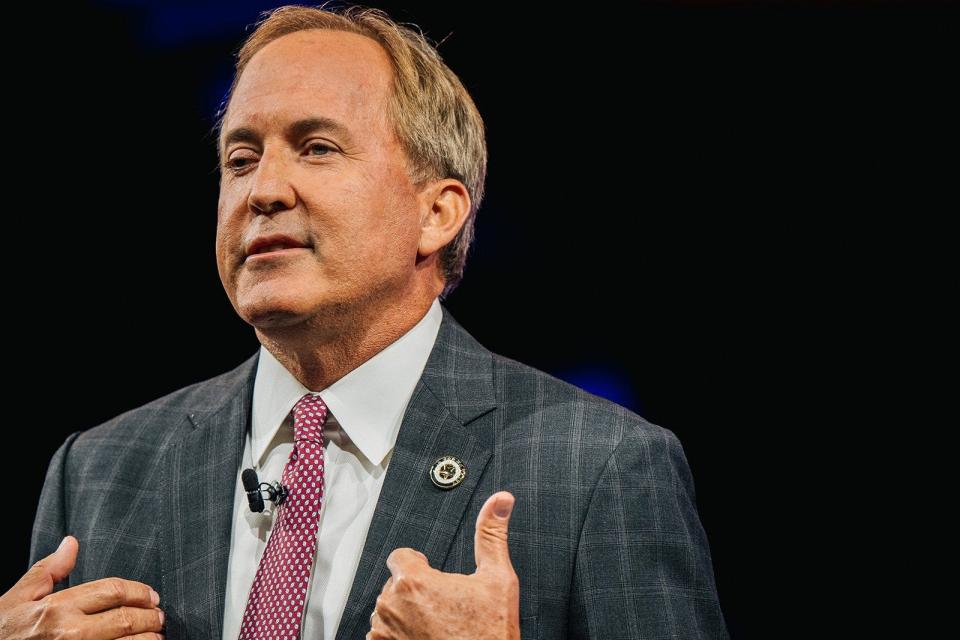

If you’re having an unnerving sense of déjà vu, it’s because over a month ago I brought you the story of Attorney General Ken Paxton’s failed effort to indict our own elections chief, the now-retired Travis County Clerk Dana DeBeauvoir, also on charges of obstructing a poll watcher in the 2020 election. (Then, as now, Paxton’s office did not respond to my requests for comment.)

RELATED: Travis elections chief says Texas AG tried 'to intimidate me'

There are similarities and differences between the two cases. But they share a disturbing theme: Paxton, a Republican, using his office’s prosecutorial powers to intimidate election officials in Democratic strongholds. The fact that grand juries in Paxton’s hand-picked venues — neighboring, more conservative-leaning counties — tossed both cases tells you all you need to know about the merit of the allegations.

Paxton’s ability to prosecute such cases is now a topic of debate. The state’s highest criminal court ruled in December that the attorney general’s office lacks the legal authority to pursue election fraud cases, saying these are matters for local district attorneys. Since then, my colleague Chuck Lindell has reported, Paxton has waged an unseemly pressure campaign urging the all-Republican Court of Criminal Appeals to reverse itself and restore his ability to prosecute violations of election law.

Paxton has argued that some district attorneys will turn a blind eye to election fraud if it helps their party, so the attorney general needs the power to prosecute those cases.

Which is pretty rich.

Icsezen’s case shows just the opposite: Paxton using the powers of his office to treat a good-faith mishap as a crime, after coming under political pressure from his own base to file charges.

“If necessary, we’ll arrange a bus and we will go down to Austin and, again, demand that (Paxton) take action,” a member of the Harris County GOP’s Election Integrity Brigade said in a video presentation recorded last spring.

Two boards, two rules

You’ve probably never heard of the Early Voting Ballot Board or the Signature Verification Committee. But trust me, you’ll want to understand this part.

Every county has an Early Voting Ballot Board. It is composed of an equal number of Republicans and Democrats. They work in bipartisan pairs to ensure the legitimacy of mail-in ballots, comparing the signatures on the ballot’s outer envelope to the signatures on file for each voter. After Election Day, these teams also review the provisional ballots, cast by people whose voting status is in dispute, to decide which ones should count.

Bipartisanship is a central feature of this board, and several members told me the environment is surprisingly collegial. The Republican and Democrat in each pair must agree for a ballot to be accepted. The board members don’t see how an individual voted, or even information like a ZIP code that might indicate political leanings. It is in everyone’s interest to accept every legitimate ballot.

“If you were to talk about the inflection points in the election process that are susceptible to fraud or problems, this would probably be the least likely to be it, because you have inherent controls in the process,” Jay Aiyer, first assistant county attorney in Harris County, told me.

Some counties also have a Signature Verification Committee, which often contains many of the same people from the ballot board. The work is largely the same, bipartisan pairs scrutinizing the signatures on mail-in ballots. The main difference is that the law allows the Signature Verification Committee to meet eight days before the ballot board can start its work. That head start is helpful for large counties handling a lot of mail-in ballots.

ALSO READ: Protecting elections starts with protecting election workers

The two boards are defined as separate entities in the election code. That is a key fact for Icsezen, who was a 2020 Democratic Party appointee to both boards in Harris County.

The election code specifically says poll watchers are allowed at the Early Voting Ballot Board.

The code says nothing about poll watchers at the Signature Verification Committee.

Icsezen raised the question with Aiyer, at the county attorney’s office, who said the committee could decide whether to admit poll watchers since the code didn’t say.

Icsezen told me he took the omission to mean poll watchers weren’t allowed at that committee.

“I don’t have the authority to say, ‘I disagree with the law, so I’m going to do things differently,’” said Icsezen, who had a leadership role as the ballot board’s presiding judge. “I didn’t think I had the authority to let a poll watcher in.”

So when a poll watcher for a Republican candidate showed up at the first day of the Signature Verification Committee’s work in October 2020, Icsezen showed her the code and turned her away.

Maybe a mistake. Not a crime.

The backlash was swift.

The poll watcher told Republican Party officials, who reached out to the Texas secretary of state, who told Harris County officials they must admit poll watchers, which Icsezen did. The whole thing was sorted out in a matter of hours.

Committee members from both parties told me the event barely registered at the time.

“We were there to do a job, and as far as I can tell from the folks I worked with, it was a non-starter. It was a non-issue,” Steven Howell, a Republican on the committee, told me. “I’m sure there were people that think democracy was placed at risk, but from the perspective of those of us in the trenches, that was never the case.”

The next week, however, an investigator with the attorney general’s Election Fraud Unit called Icsezen. They sat down for a December 2020 interview that Icsezen thought would clear everything up.

I’ll pause here for a moment to say that I believe in government transparency, especially around elections. I wish Icsezen had erred on the side of letting the poll watcher in.

But the fact remains: The code was silent on this point, leaving election workers to guess what the rules should be. Icsezen said he tried to make the best call after consulting with a county attorney who agreed with his course of action.

At worst, this was a good-faith mistake. This was not a crime.

Paxton’s office did not respond to my questions about this case, but communications from the Harris County Republican Party suggest the attorney general’s office was initially underwhelmed. A form letter drafted by the party’s Election Integrity Brigade, urging Paxton’s office to prosecute Icsezen, says a prosecutor indicated “the case is flawed by a ‘mistake in the law.’”

Still, the form letter asserted the attorney general’s failure to prosecute was a “blatant dereliction of duty.” The brigade sent an email blast to Harris County Republicans in March, asking them to copy and send the form letter to Paxton and 21 other elected Republicans.

“Respectfully, if the (Office of Attorney General) does not move on this case, we have no confidence that the Attorney General will uphold any of our election laws,” the letter said.

'Paxton heard us'

Bill Ely, the Harris County Republican Party member who sent that email blast, said he believes the letter-writing campaign made an impact.

“It was reported to me that Paxton had heard us,” Ely told me.

Ely directed questions about the party’s efforts to Alan Vera, who chairs the Harris County GOP’s Ballot Security Committee. Vera did not respond to my request for comment.

ALSO READ: Paper voter registration system is 'absurd.' But Texas does it anyway

Icsezen heard about the letter-writing campaign at the time, but he dismissed it as "partisan junk.” He was stunned to see the press release last July announcing Paxton’s office had tried, and failed, to indict him.

Prosecutors typically don’t announce their failure to indict someone unless it’s a high-profile case. Icsezen is hardly a household name. The fact that the attorney general’s office bothered with a press release tells me that Paxton wanted to show the Harris County Republicans: Here. I tried.

Cases like this have a broader chilling effect, though — especially now that the voting restriction bill passed by the Legislature last fall defines new crimes. (Notably, the new law also says poll watchers can attend the Signature Verification Committee, a tacit admission that the old law was unclear.)

Remi Garza, president of the Texas Association of Elections Administrators, told me that people who have long served as the presiding judge of a voting precinct no longer want the responsibility of being in charge.

“They’re fearful that, by mistake or omission, they would be subject to criminal investigation or even prosecution,” said Garza, who runs elections in Cameron County.

This trend deeply worries me. We need good, honest people — from partisan ballot board members to nonpartisan county election workers — to make our elections possible. The push to criminalize mistakes is already scaring some of them away.

Icsezen told me he stepped down from the election boards last year, but not out of fear. “I did not want to give them a reason to call into question the elections in Harris County,” he said.

Still, I was heartened by my conversations with several other ballot board members who knew all about Icsezen’s plight and remained undeterred.

Andrea Greer, a Democrat, described working with her Republican counterpart to sort out the confusion over a father and son with the same name, ensuring both men’s votes would count. She described the team’s careful work to determine that an older woman’s mail-in ballot would count, even though the voter’s deteriorating health made it too hard for her to sign her name.

“We told her that her vote counted, and she cried,” Greer recalled, her voice welling with emotion. “That’s important. I’m willing to be the target of the attorney general for people like that woman.”

Grumet is the Statesman’s Metro columnist. Her column, ATX in Context, contains her opinions. Share yours via email at bgrumet@statesman.com or via Twitter at @bgrumet.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Democratic election worker says Texas AG 'tried to throw me in jail'