Guest column: Labor Day is more than burgers on a grill

A 15-year-old immigrant girl working from midnight to 6 a.m. may have packaged your morning cereal. An eight-year-old child may have helped grow your luncheon vegetables and a 14-year-old may have processed the chicken you had for dinner.

“Are we actually arguing about whether 14-year-olds should work in meat-packing plants,” asks Terri Gerstein, a fellow at Harvard Law School for Labor and a Just Economy.

To solve a labor shortage, we need higher wages, safe work places and better jobs. We do not need more child labor,” Gerstein says. She contends that the U.S. labor shortage should not be a surprise, however. Many employers, especially in low-wage industries, “were cavalier” with their employees’ health during the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic and more than one million died. Long COVID is keeping another million out of the workplace, and, among those 65 and older, two million never returned to work after the pandemic.

So, according to Gerstein, businesses are turning to the most vulnerable: children.

Migrant children and youth may be the most at risk. Many came to the U.S. southern border alone. Politicians wanted them off the border as quickly as possible, but did not allocate funding for sponsors to be vetted or tracked. The Department of Human Services was overwhelmed and unable to follow-up on what has happened to these youngsters. To compound the problem, the Department of Labor does not have the necessary tools to stop labor violations.

A New York Times exposé in February says that there is a “shadow workforce of migrant children across industries in every state: 12-year-old roofers in Florida and Tennessee; 13-year-old girls washing hotel sheets in Virginia; a 13-year-old boy making auto parts on an overnight shift that ends at 6:30 a.m.; a 12-year-old working for a Hyundai subsidiary in Alabama.”

Often working more than full-time, these children have no way to go to school.

Even the good laws around child labor are hard to enforce when the enforcement agencies are underfunded. The U.S. Labor Department has been underfunded for decades, and many companies using child labor have little fear of getting caught, according to the exposé.

The United States did not address child labor until 1938, when the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed. That Act, unfortunately, exempts farm labor on the outdated notion that we are an agrarian society. Although abuses among farm laborers are, therefore, by and large legal, they are still terrible abuses. Children should not be exposed to chemicals in pesticides and fertilizers used on farms. (Probably nobody should be exposed to them.)

Certainly not perfect, still the federal child-labor law generally prohibits the employment of minors in nonagricultural occupations under the age of 14, restricts the hours and types of work that can be performed by minors under the age of 16 and prohibits the employment of minors under the age of 18 in any hazardous occupation.

Not all child labor is migrant child labor. Gov. Sarah Huckabee signed a bill in Arkansas earlier this year rolling back the state’s child-labor protections, making it easier for employers to hire 14-year-olds.

The largest industries by revenue in Arkansas are beef and poultry slaughterhouses, where the work is nasty and dangerous. And, sadly, impoverished families let their children take survival jobs even when they are dangerous.

Workers under the age of 25 are injured at disproportionately high rates. A report by the Government Accountability Office suggests that 100,000 child farmworkers are injured on the job every year and that children account for 20% of farm fatalities. A 16-year-old boy was killed in Georgia when he fell from an earth-moving machine he was operating and it ran over him.

To be clear, I hope every teenager who wants one can find an age-appropriate job in a safe environment. I hope children in farm families will always help with chores. I am not writing about appropriate part-time jobs. I am writing about abusive, illegal treatment of children and young teens.

“Stories of kids dropping out of school, collapsing from exhaustion and even losing a limb to machinery are what one expects to find in a Charles Dickens or Upton Sinclair novel, but not an account of everyday life in 2023, not in the United States of America,” said Rep. Hillary Scholten in a fiery February speech on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Although the Lorax was talking about the environment. Dr. Seuss’s quote attributed to the Lorax fits so many situations: “Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.”

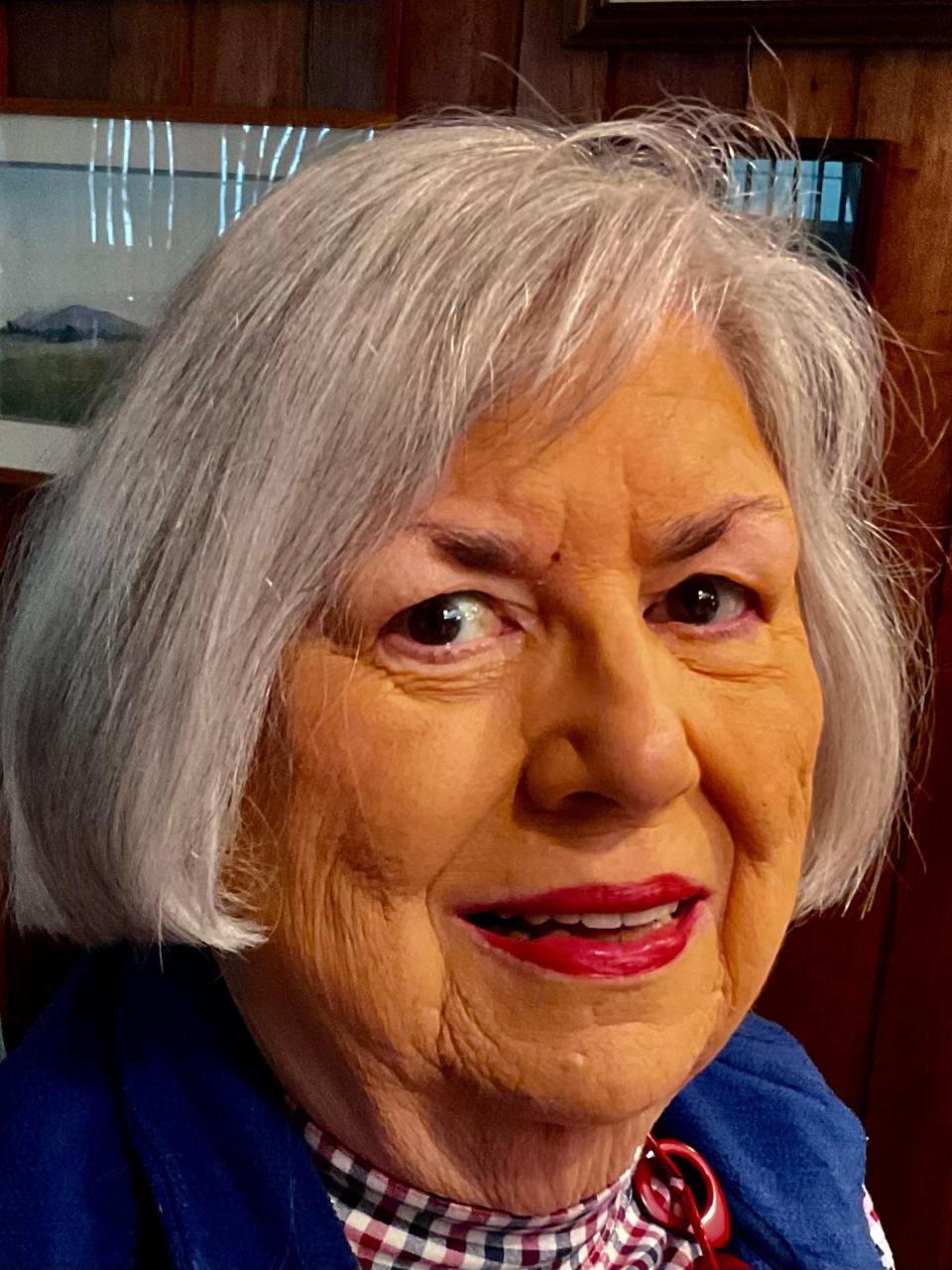

Martha Moore Hobson was an early Certified Financial Planner in the region. Although retired, she volunteers in the community and has contributed to The Oak Ridger for some 25 years.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: Labor Day is more than burgers on a grill