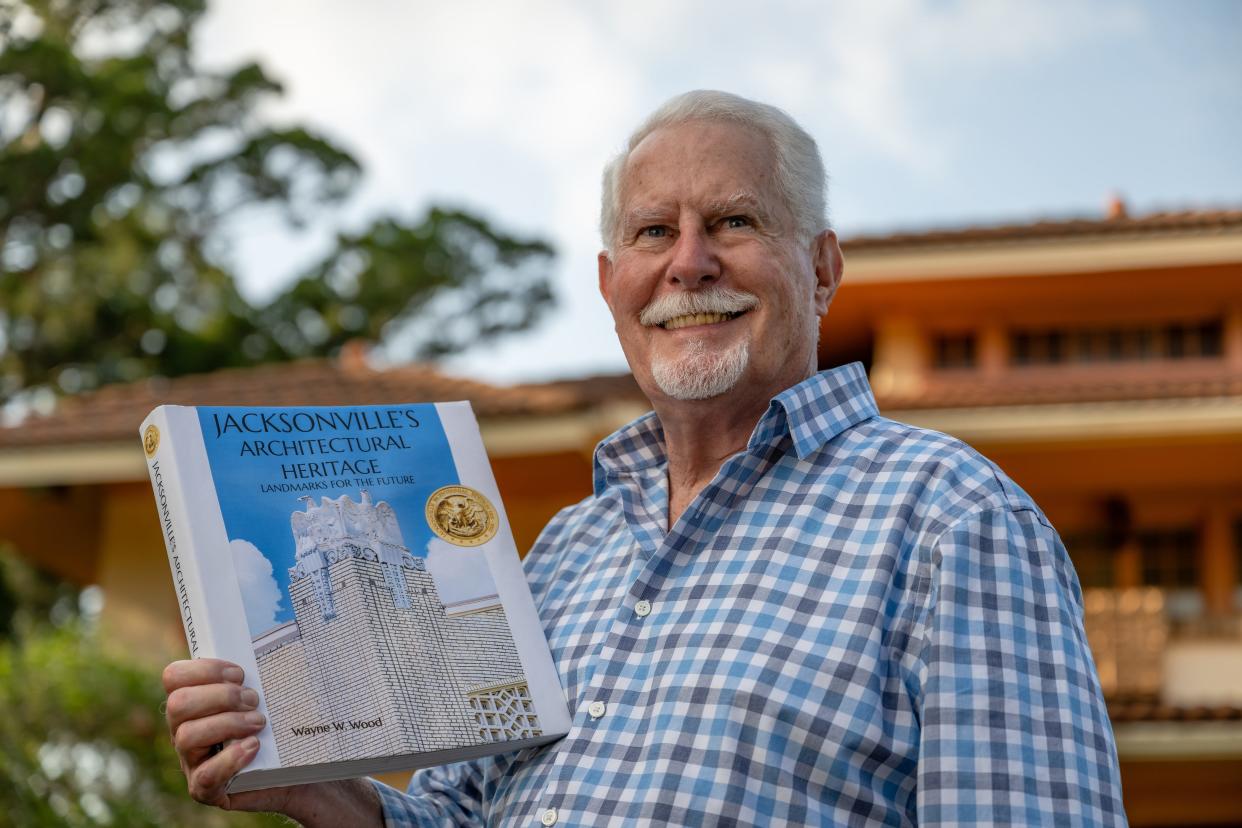

Guest column: Wayne Wood's new book is 'the legacy I want to leave to Jacksonville'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Wayne Wood’s grandparents owned a boarding house on Riverside Avenue called The Woodshed. As a child, Wood, now 77, spent summers there, enjoying the splendor of that house and other grand homes in the neighborhood.

His grandparents weren’t wealthy people.

“But in an important sense they were rich,” Wood said. “They lived in a house that was every inch a work of art.”

Today only a handful of the striking homes that once filled that neighborhood near the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens survives.

After Wood moved to Jacksonville in the early 1970s to practice optometry, he became involved in the effort to preserve some of the city’s architectural splendor.

Lasting legacy: Early architects put their stamp on Jacksonville

Call Box: Wayne Wood’s Prairie-style dwelling

Architecture is “perhaps the most fragile of all the arts,” Wood said in a recent interview. “A decade after the Great Fire of 1901, Jacksonville had become a gleaming modern city. Sadly a century later the vast majority of those downtown buildings constructed after the Great Fire were gone. The loss of so many beautiful buildings in the downtown and in the older neighborhoods by the early 1970s finally caught people’s attention.”

It certainly caught Wood’s attention. He became a founder of Riverside Avondale Preservation in 1974. Beginning in 1977, he was part of the Jacksonville Historic Landmark Commission, which in 1989 published “Jacksonville’s Historic Heritage: Landmarks for the Future.” Wood served as author and designer of the book.

Now he has returned to the subject with his 15th book, known as “Jacksonville’s Architectural Heritage: Landmarks for the Future.”

The original book documented 612 sites, 470 of which are included in the new book. A total of 126 sites from the old book have been demolished, and there are 16 others that Wood chose not to include in the new book. He added 390, bringing the total to 860 sites.

“It’s a totally new book,” Wood said. “The old book is obsolete.”

Some of the buildings now included simply weren’t old enough to qualify for the 1989 book, which did not include buildings less than 50 years old.

“We were constrained then by the fact it was published by the city,” Wood said.

For the new book, Wood decided to include some sites, such as the Chart House restaurant, built in 1982 on the Southbank, because their architectural significance superseded their age.

There is even a Buddhist temple, Wat Kanteyaram on the Westside, that was not completed until 2013.

“Architecturally it is stunning,” Wood said of the temple. “It has a great story to tell. Every building has its story. As I did this book, I would imagine I was standing in front of a building with my father and answering the question, ‘Why is this significant?’ This is the book I wanted to write. It’s the legacy I want to leave to Jacksonville.”

The first book sold 3,000 copies in less than two weeks, with 26,000 copies eventually printed and sold. Wood said he’s seen copies selling for as much as $200.

The new book will be offered for $64.50. That price is only possible because the book has been underwritten by grants from Preston Haskell, the Jessie Ball duPont Fund and the Ida M. Stevens Foundation. All proceeds go to the Jacksonville Historical Society.

Some sites featured in the book

DOWNTOWN

Jacksonville Free Public Library, 101 E. Adams St., architect H.J. Klutho, 1903-1905.

In 1903 philanthropist Andrew Carnegie gave Jacksonville $50,000 to build a free library. Henry Klutho gave a Neo-Classic Revival design to the building that served as Jacksonville’s main library until 1965. In 1983 it was purchased from the city and renovated by the law firm of Bedell, Dittmar, DeVault, Pillans & Gentry.

St. James Building, 117 W. Duval St., architect H.J. Klutho, 1911-1912.

Prior to the 1901 fire, this site was occupied by the St. James Hotel. Jacob and Morris Cohen, owners of Cohen Brothers’ store, purchased the lot in February 1910 and commissioned H.J. Klutho to design a department store. The result was the largest building in Jacksonville and the ninth-largest department store in the United States. After the May Cohens store closed, the building was renovated to become Jacksonville’s City Hall in 1997. It is believed to be the largest Prairie-style building in the world.

Old Florida National Bank; aka The Marble Bank, 51 W. Forsyth St., architects Edward Glidden, W.B. Camp, Mowbray & Uffinger, 1902, 1906, 1916.

Built in 1902 as the Mercantile Exchange Bank, it was purchased three years later by the Florida Bank & Trust, the forerunner of the Florida National Bank chain. In the 1980s the bank closed. Restoration of “the Marble Bank” as part of the Laura Street Trio is a major priority for the city.

LA VILLA

Old Stanton High School, 521 W. Ashley St., architects Mellen C. Greeley, W.B. Ittner (supervising), 1917.

In 1868 a 1.5-acre city block was purchased and a school for formerly enslaved people and free Blacks was built. A former student at the school, James Weldon Johnson, returned in 1894 to become a teacher and later the principal of Stanton. While serving at Stanton, Johnson wrote “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” with his brother, John Rosamond Johnson, which became known as the Negro National Anthem. Stanton was closed as a school in 1971.

MID-WESTSIDE

Bishop Henry Y. Tookes residence, 1011 W. Eighth St., 1939.

Of all the big houses owned by affluent African Americans along West Eighth Street in the Black middle-class neighborhood of Sugar Hill, the home of Bishop Henry Tookes and his wife Maggie may have been the grandest of all. It is the only one that survived the construction of a restricted access highway that became Interstate 95.

BROOKLYN

Mount Calvary Brooklyn Church, 301 Spruce St., architect James Edward Hutchins, 1949.

The church began in 1892 with a one-story wooden building. When its ninth pastor, the Rev. William Hill, arrived in 1942, he hired Hutchins to design the new church. It was moved from Brooklyn to a new location in 1999.

RIVERSIDE AND AVONDALE

1816 Avondale Circle, architect Mellen Greeley, 1927.

Greeley felt this house, known as the “Birdhouse House,” was one of his best residential designs. It won the gold medal of the Architecture League of Jacksonville in 1927 when it was built for attorney Frank Holt. The Tudor Revival style was very much in vogue during the Florida real estate boom of the 1920s.

Martha Washington Hotel, 1636 King St., 1911.

At the time of its construction, this three-story Colonial Revival house was one of the largest mansions in “Riverside Annex,” as the area around King Street was then known. In 1938 the building became a hotel with a large addition added to the back. It continued as a residential hotel until 1977 when it closed and was slated for demolition. A group of investors organized by Riverside Avondale Preservation came forward to save it and it was converted into condominiums.

The Fenimore Apartments, 2200 Riverside Ave., architects Mellen Greeley and Roy Benjamin, 1922.

The Fenimore Apartments building was the first project for the newly formed architectural team of Benjamin and Greeley. While Benjamin was in Texas, Greeley designed the Fenimore. The building’s most prominent features are the numerous recessed balconies and white cast-stone trim.

EASTSIDE

Old St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church, 317 A. Philip Randolph Blvd., architect Robert Schuyler, 1887.

This Gothic Revival Church is the largest pre-1901 house of worship in Jacksonville. The congregation moved to the suburbs in the 1960s and the building sat vacant and deteriorating for nearly 30 years. It was acquired by the city and restored in 1998 under the guidance of architect Ted Pappas. It now serves as an event venue for the Jacksonville Historical Society.

Meet Ted Pappas: The Jacksonville architect behind some of the city's iconic buildings

Zora Neale Hurston Residence, 1473 Evergreen Ave., 1904.

Author Hurston was a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance. She moved to Jacksonville in 1901 to live with her older brother in this one-story house. After moving to New York and achieving recognition in the literary world, Hurston returned to Jacksonville to work as a folklorist for the Federal Writers’ Project with Stetson Kennedy in 1938 and 1939. Her work became part of Kennedy’s acclaimed "WPA Guide to Florida" and "The Florida Slave."

SPRINGFIELD

W.B. Barnett residence, 25 E. First St., architect Leon Beaver.

After the 1901 fire destroyed his downtown residence, William Barnett, the founder of Florida’s Barnett Bank chain, had this elegant mansion constructed in Springfield in the Colonial Revival style. The Barnett family sold the house in 1941 to Solomon Lodge, the city’s oldest Masonic organization.

First Church of Christ Scientist, 101 W. First St., architects Marsh & Saxelbye, 1921.

Today it’s the Karpeles Manuscript Library Museum, which houses rare and historic manuscripts. Originally it was built for the First Church of Christ Scientist. Its imposing Neo-Classical Revival façade highlighted by monumental Doric columns creates an impressive entrance to Springfield.

Henry John Klutho residence, 30 West Ninth St., 1909.

The first Prairie-style house in Florida was the residence at 2018 Main Street designed by Klutho, the prominent architect who moved to Jacksonville after the fire of 1901. It was originallybuilt on Main Street. With the decline of Klutho’s finances, he sold the lot on Main Street in 1925 and moved the house around the corner to its present site. Klutho moved back into this building in 1935, living out his life in a second-story apartment.

'Radical' masterpiece: Here's your chance to own renowned architect Henry Klutho’s home

NORTH JACKSONVILLE

A.L. Lewis Mausoleum, 6013 Moncrief Road, Memorial Cemetery, architect Leeroy Sheftall, 1939.

Born in poverty, by 1901 Lewis became one of the seven founders of the Afro-American Industrial & Benefit Association, a company that first specialized in low-cost health and burial insurance for the Black community. By the time of his death in 1947, the company (known as the Afro-American Life Insurance Co.) had become the largest Black-owned business in Florida.

WEST JACKSONVILLE

Wat Kanteyaram Temple, 4057 Hunt St., 2013.

The Wat Kanteyaram Temple began in a small nondescript bungalow for Cambodian Buddhists in the Lackawanna neighborhood in 1987. That house was demolished in 2008 and construction began on the three main buildings in the temple complex, which was completed in 2013 at an estimated cost of $2 million.

ORTEGA

“The Gangster House,” 2815 Grand Ave.

In July 1933 George “Machine Gun” Kelly and his wife Kathryn were suspected of kidnapping Texas oil man Charles Urschel who paid $200,000 for his release. On Sept. 27, 1933, Kelly and his wife were arrested in Memphis. But according to long-standing rumors they had spent part of the summer hiding out at this house in Ortega. There were even reports that they may have fled the house ahead of a police raid via a tunnel leading to the river.

Machine Gun Kelly: Legend of the Ortega Gangster House lives on

“Los Cedros,” 4765 Ortega Blvd., Marion Sims Wyeth architect, 1925.

Los Cedros is one of the grand riverfront Mediterranean Revival villas in Jacksonville, surpassed only by Epping Forest. Architect Marion Sims Wyeth spent three months in Spain studying Spanish architecture prior to drawing the plans for this house. The residence was built for Raymond C. Turck, the chief surgeon at St. Luke’s Hospital from 1910 to 1916. Turck named his home “Los Cedros,” after the majestic rows of cedars that line the entrance to the house.

SOUTH JACKSONVILLE

South Jacksonville City Hall, 1468 Hendricks Ave., 1915.

South Jacksonville was incorporated as a town in 1907, at which time the population was about 600. In 1913, 96 qualified voters cast ballots to pass a $65,000 bond issue for civic improvements, which included the construction of this City Hall building. South Jacksonville was absorbed into Jacksonville in 1932. The San Marco Preservation Society spearheaded an extensive restoration of this building, which became headquarters for the neighborhood organization in 2008.

Chart House restaurant, 1501 Riverplace Blvd., Kendrick Bangs Kellogg architects, 1982.

Kellogg is a San Diego-based architect who is recognized as one of the founders of the modern organic architecture movement. The Jacksonville Chart House is one of his few commissions in the eastern United States and is arguably one of Jacksonville’s most internationally recognized buildings. The Florida chapter of the American Institute of Architects named it one of the top 100 buildings in the state.

Gulf Life Tower, 1301 Riverplace Blvd., Welton Becket of KBJ architect, 1967.

Over 50 years after its completion, this building, now known as Riverplace Tower, is still Jacksonville’s greatest modern skyscraper and was once the tallest concrete structure in the world, a distinction it held until 2002.

SAN MARCO

San Marco Theatre, 1996 San Marco Blvd., architect Roy A. Benjamin, 1938.

The theater’s Art Deco façade adds a jazzy touch to the ambiance of the San Marco business district. The theater opened on July 4, 1938, featuring the double bill of “Hopalong Cassidy Rides Again” and Edward G. Robinson in “A Slight Case of Murder.”

The Little Theatre, 2032 San Marco Blvd., architect Ivan H. Smith, 1937.

San Marco Square features several Art Deco buildings, reflecting the shopping center’s peak years of development in the 1930s. Completed six months before the San Marco Theatre one block away, the Little Theatre is now known as Theatre Jacksonville. It originated in 1920 as the Community Players, and its performances were staged in various auditoriums throughout the city until the completion of the present facility, made possible through a donation by Carl Swisher.

John H. Swisher residence, 2252 River Road, architects Marsh & Saxelbye, 1930.

In 1861 a small cigar-making business was given to David Swisher, a merchant in Newark, Ohio, as payment for a debt. In 1913 his son John and grandson Carl took it over and gave it the name “Jno. H. Swisher & Son.” In 1924 they moved their operation to Jacksonville where they manufactured King Edward cigars, which for several decades was the largest-selling brand of cigars in the world. Within five years after arriving in Jacksonville, John Swisher had completed the plans for an elegant riverfront residence in San Marco, and construction began at the same time on his son’s similar house next door.

Tobacco Road: Historic former Swisher estate goes on the market for $5.75 million

SAN JOSE

Epping Forest, 6814 San Jose Blvd., architects Marsh & Saxelbye, 1927.

The Florida land boom attracted the attention of many investors, including Alfred I. duPont, a multimillionaire from Wilmington, Del. In 1921 duPont married Jessie Dew Ball, his third wife, and in 1927 they moved to Jacksonville. The duPonts' new estate included over 60 acres and nearly a mile of waterfront. Alfred I. duPont died on April 29, 1935. Jessie Ball duPont died in 1970 at the age of 86. Epping Forest was then placed in the custody of her brother, Ed Ball, a powerful financier in his own. In 1972 Ball sold Epping Forest to Raymond Mason, chairman of the Charter Co. In 1984 it was purchased by Herb Peyton, president of Gate Petroleum Co., and the estate was converted to a yacht club with condominiums constructed around it.

THE SOUTHERN CRESCENT (St. Nicholas, Keystone Bluff, Empire Point, Oak Haven, Clifton)

“Wacca Pilatka,” 1235 Mayfair Road, architect Robert Broward, 1993.

Broward designed this three-story riverfront home for himself and his wife, Myrtice Craig, reflecting the influence of both early Florida “cracker” houses and his apprenticeship with Frank Lloyd Wright. Broward named the house “Wacca Pilatka” after the nearby Native American crossing point of the St. Johns River.

St. Elmo W. Acosta residence, 4455 Atlantic Blvd. on the Episcopal High School campus, 1885.

Acosta, a long-time Jacksonville political leader, built his home near an orange grove on the Southbank of the St. Johns he had enjoyed visiting as a schoolboy in the 1880s. He is best remembered today as a passionate advocate of bridges across the St. Johns River that accommodate both pedestrians and automobiles. One such bridge is named for him.

Marabanong, 4749 River Point Road, circa 1876.

In 1870 Thomas Basnett, a noted astronomer from England, built a towering ornate mansion overlooking the St. Johns River in what would become the Empire Point neighborhood. The mansion was given the name “Marabanong,” thought to be a native New Zealand Maori word for “Paradise.” However, Maori language experts have refuted this. Although the once spacious riverfront property at Marabanong has been divided with the construction of a number of single-family residences on the site, the original mansion remains well-preserved. The two-story veranda is Jacksonville’s most impressive porch, Wood writes, with its lathe-turned posts and spindles totally encircling the 6,000-square-foot house, which contains 21 rooms, 5 baths, and 121 windows.

ARLINGTON

Eagle Film City (Norman Film Studios), 6337 Arlington Road, 1900 to 1915.

More than 30 motion picture studios operated in Jacksonville from 1908 to 1922 leading the city to bill as “The World’s Winter Film Capital.” One of the last studios to open was “Eagle Film City” in Arlington Heights. Within a year after the Eagle Studios opened, the entire movie industry in Jacksonville began a rapid decline. Eagle was one of only three studios still operating in Jacksonville by the end of World War I. In 1922 Richard E. Norman purchased the bankrupt studio and continued production into the 1930s. He made short-subject features and adventure movies starring all-Black casts. Through the efforts of preservationists Rita Reagan and Ann Burt, this site, with the five wooden buildings remaining from the old movie studio, is being preserved and restored as a museum of Jacksonville’s silent movie era. Norman Studios became a National Historic Landmark in 2016.

Race films: Norman Studios looking to reopen Arlington filmmaking museum, expand campus

Unitarian Universalist Church, 7405 Arlington Expressway, architect Robert C. Broward, 1965.

This is another Jacksonville structure selected as one of the “Top 100 Buildings” in Florida. Broward, a member of the church, camped out on the three-acre vacant property for days to envision how the building could be built on the challenging site. The church is made of wood and unpainted Ocala block (a concrete block with high limestone content, resulting in its beige tone).

Geodesica, 6863 Howalt Drive, architect Gilbert D. Spindel, 1959.

The round house “Geodesica” caused quite a stir in the 1959 showcase sponsored by the Home Builders’ Association, with cars backed up for six blocks. Looking futuristic even today, the house has a remarkably convenient floorplan, with wedge-shaped rooms surrounding a central sunken living room. Like a number of architects of the 1950s, Spindel sold “plan books,” booklets that contained detailed house plans. The novel concept of this house was apparently popular; at least six other “Geodesicas” based on Spindel’s plans have been located across the country.

MANDARIN

Mandarin Store and Post Office, 12471 Mandarin Road, architect William Monson, 1911.

Monson built this store on property he owned at the corner of Mandarin and Brady Roads. Postmaster Walter Jones leased the building and went into business for himself starting a general store in part of the building. Villagers stopped to buy groceries, pick up their mail, and hear the latest news. The building now belongs to the Mandarin Community Club. It was restored in 1998, is on the National Register of Historic Places, and is operated by the Mandarin Museum & Historical Society as a small museum.

Walter Jones Historical Park, 11964 Mandarin Road.

Major William Webb’s home, barn, and dock were purchased in the early 1900s by postmaster Walter Jones, whose family lived there for nearly 90 years. The property opened as a historical park in August 2000, and it includes a museum of Mandarin history, as a well as the restored Webb/Jones farmhouse, a barn, a winery, a sawmill, a historic schoolhouse, and a nature trail along a riverfront boardwalk. The Mandarin Museum & Historical Society operates the museum and park facilities under a contract with the city of Jacksonville.

JACKSONVILLE BEACH

Casa Marina Hotel, 12 Sixth Ave. N., architects Marsh & Saxelbye, 1925.

The Casa Marina is the last in a long line of grand hotels from the early days at the Beaches. Fire destroyed the Murray Hall Hotel, the Burnside Hotel and the Atlantic Beach Hotel, all wooden structures. Learning from the demise of these older hotels, the builders of the Casa Marina constructed what they boasted was “the only modern fire-proof hotel at the World’s finest beach.” It opened on June 6, 1925.

St. Paul’s by-the-Sea Episcopal Mission, 525 Beach Blvd., architect Robert S. Schuyler, 1887.

The parlor of the Murray Hall Hotel housed the first organized religious services at the Beaches in 1886 when a handful of Episcopalians gathered to worship. Guests of the hotel and permanent residents of Pablo Beach soon donated $800 to construct a building for church services. But as time passed this mission church struggled for survival, often having no minister available for weeks at a time. In 2012 the church was moved for its fourth and final time to its current location at the Beaches History Park. It is now known as the Beaches Museum Chapel and is used for weddings and other special events.

NEPTUNE BEACH

Pete’s Bar, 117 First St., 1938.

In the 1920s, Danish immigrant Pete Jensen founded Jensen’s Market. At the end of Prohibition in 1933, Jensen acquired the first liquor license in Duval County, and in 1938 he built a one-story concrete block building, which not only contained his bar but several other businesses. Over the years the bar took over the entire building and was operated by five generations of the Jensen family until it was sold in 2021. This landmark watering hole was featured in John Grisham’s book, “The Brethren,” and hosted such other littérateurs as Ernest Hemmingway and J.D. Salinger.

ATLANTIC BEACH

William & Bunny Morgan residence, 1945 Beach Ave., architect William Morgan, 1972.

This soaring expanse of wood and glass that Morgan built as his own home is spatially complex, with two intersecting triangular masses forming an extension of the dune upon which the house rests. The street side is enclosed in a steep roof, whereas the ocean side consists of four terraced levels that ascend the slope of the dune and open to the ocean. This creates large, flowing interior spaces and makes it one of Morgan’s most famous buildings.

Dune Houses, 1941-43 Beach Ave., architect William Morgan, 1975.

Using the topography of the hurricane-damaged dune as inspiration, Morgan designed this as an exclamation point in his lifelong exploration of earth architecture. He created two 2.5-inch thick egg-shaped concrete shells, joined by a common wall, to create two underground apartments. The openings on the ocean side feature sliding glass doors and provide views of the beach. The steepness of the dune allowed construction of two stories of living space within a compact area. The Dune Houses were first featured in Playboy magazine and, although this is one of Morgan’s smallest buildings, it continues to be one of his most internationally acclaimed works.

MAYPORT

Old St. Johns Lighthouse, U.S. Naval Station Mayport, 1858.

The lighthouse is the oldest structure in Mayport and the Beaches. Just seven years after Florida became a territory of the United States in 1821, Congress appropriated $6,500 for construction of a lighthouse to mark the mouth of the St. Johns River. In 1858 the present lighthouse was constructed, both taller and farther from the shoreline than its predecessors. During the Civil War, Confederate sympathizers shot out the light to make it difficult for Union gunboats to find the channel, and it was not repaired until 1867. In 1887 the upper canopy of the lighthouse was modified, including the installation of the present copper dome.

FORT GEORGE ISLAND

Kingsley Plantation house, 11676 Palmetto Ave., 1798.

After the American Revolution Zephaniah Kingsley established a career as a West Indies merchant and an African slave trader. In 1813 Kingsley moved into a plantation house on Fort George Island. A non-conformist who scorned organized religion and was polygamous, Kingsley chose as his primary wife Anna Madgigine Jai, an enslaved African who presided over his household. The house is now owned by the National Park Service.

Napoleon Bonaparte Broward’s home, 9953 Heckscher Drive, circa 1878

Born in Duval County in 1857, Napoleon Bonaparte Broward became one of this city’s most colorful characters. Orphaned at age 12 and self-educated, he built the steam tugboat Three Friends in 1895 and ran guns to Cuba. Broward’s illegal activities made him popular with many Floridians. Soon he was elected Duval County sheriff and was subsequently a member of the City Council from 1895-1897. In 1901 he was elected to the Florida House of Representatives, and in 1905 he became governor of Florida. He is thought by many scholars to have been one of Florida’s greatest governors. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1910 but died before he could assume office. Although he and his wife already owned a fashionable home, they maintained this house in 1857 on Batten Island as a summer home. It is now owned by the National Park Service.

Charlie Patton is a former longtime Florida Times-Union reporter.

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Wayne Wood writes second Jacksonville Architectural Heritage book