A Day-By-Day Guide to What Could Happen If This Election Goes Bad

The coronavirus pandemic was always going to make the 2020 election uniquely complicated, and Donald Trump’s norm-busting style was always going to make it tense, but headlines in recent days have started to read like political thriller plot lines. We’ve seen Iranian skullduggery, dummy ballot boxes and mysterious threatening emails. Congressional Democrats are pleading with the military to respect a peaceful transition of power. A poll shows that barely a fifth of Americans believe this year’s election will be “free and fair.” There’s concern about violence, especially by militias and white supremacists. Some Americans are even laying in extra food and water, fearing what comes next.

Americans have little experience navigating disputed elections at this scale, and none at all doing so with a president hinting he might not leave office if he loses.

So what could we really be in for after November 3? Beyond a vague, crippling sense of dread, a feeling informed by hours of late-night doom-scrolling, what could actually go wrong?

The closer we get to the election, the more the picture comes into focus. Three months ago, POLITICO Magazine surveyed experts about what could go wrong on Election Day itself—from voter suppression to sinister “poll-watchers” to complete voting chaos—and as the day approaches we asked more than a dozen election, constitutional and national security experts about the concrete problems they’re planning for once the polls close.

Some have already been involved in “wargaming” scenarios for a bitterly contested election; others have been busy gathering legal memos to plan for this contingency or that or enlisting corps of lawyers and observers to deploy on Election Day and to any trouble spots in the days that follow. Their fears run from a narrow election night Trump lead in Arizona to a reprise of the 2000 “Brooks Brothers riot”—this time with AR-15 rifles—to the outsized importance that might weigh on Montana’s sole congressional race if the presidential race ends up in the House of Representatives.

One bit of good news: The U.S. election system is relatively resilient and guided by strict legal procedures, so we can expect the uncertainty—tense as it may be—to unfold with distinct phases. “There are different points where we’ll know what kind of world we’re living in,” says Stanford Law School election expert Nathaniel Persily. “Every nightmare scenario begins with the early states not being decisive and the absentee vote in Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin being outcome determinative. We’ll know within four hours of polls closing whether we live in that world.”

“If Biden wins by 2, 3, 4 points, we’re in this world,” says one Democratic strategist who spoke anonymously to avoid letting on that his group is involved in preparing for a contested election. “The 4-to-6-point range is still pretty significant. Even if there are no shenanigans and it’s a clean count, the Electoral College bias probably requires getting to 3 or 4-point margin of victory for a Democrat before you win the Electoral College too.”

What should we start worrying about, and when? Below, we’ve pulled their insights into a chronological guide: What to watch for in the minutes, days, weeks and months after voting ends on Nov. 3.

And one final note of reassurance amid what can be an unsettling picture: Our experts think chances are extremely high that the nation will swear in a duly elected commander in chief on January 20, 2021. Here’s what that road to that moment could look like:

Voting is extended

Every election has glitches. Poll workers show up late; power goes out; electronic machines fail. In 2018, one polling place in Phoenix was actually foreclosed on the night before the election, forcing officials to scramble to move it. Such incidents invariably lead to court requests to extend poll hours, a routine legal remedy. Beyond court-ordered extensions, voters already in line at the time polls are supposed to close may stay to cast their votes, so in the event of long or slow lines on Election Day, we may not see voting wrap up until late in the evening of November 3 or even early Wednesday morning.

None of those problems end up mattering in the final, official counts. Normally. But in a year when nothing is normal and everything is under the microscope, these problems will have repercussions we don’t normally see. You can expect perfectly normal swing-state glitches to pump fuel into the right- and left-wing panic machines on Election Day and beyond. And since news organizations have rules against “projecting” winners in states until polls have closed across the entire state—and are planning to be extra-cautious about early calls this year—these issues may delay the unofficial win/loss tallies on election night. So even if everything is buttery-smooth, you can expect an unusually late night, and widespread coverage of even what are routine glitches.

False or premature claims of victory

Few scenarios seem more likely, and more indicative of trouble ahead, than the candidates rushing out on election night to claim victory long before the votes are fully counted. “If you think about the fog of war in the 24 hours after the polls close, there’s going to be a competition to explain what’s taking place by the candidates, the news media, perhaps even foreign actors,” Stanford’s Persily says.

Changes in voting behavior and reporting patterns in recent years have led to what political scientists have taken to calling the “blue shift” or “red mirage”—a rush of Republican votes reported early that give way to more Democratic votes as more jurisdictions and ballots are counted. (The exact reasons behind this clear and pronounced new trend in U.S. voting remain hotly debated by political scientists, but it’s been steady since 2004.) States like Arizona, for instance, have consistently seen a move of about 4 points in favor of Democrats as final votes are tallied. Nationally, when Trump took the stage to declare victory at 2:49 a.m. ET in 2016, he led Hillary Clinton by a million votes—57 million to 56 million—but the final tally had Clinton beating him in the popular vote by nearly 3 million, 66 million to 63 million.

The way these shifts play out state-by-state may matter a great deal in forecasting the initial trends—and who tries to leap out and claim victory when. “If Donald Trump is up by 2 points at midnight in Arizona, that could create a real problem as his supporters think he’s victorious,” says one Democratic strategist.

So one major anxiety is that Trump will seize on early favorable results to declare victory—before the election has been called either way—and point to any later shift as evidence of fraud. “After the votes are in, the game on his side is tell a different narrative about what happened—there was fraud and we won—and provoke an antagonistic or violent reaction to precipitate a law and order crisis,” says one election strategist, who worries Trump could then put pressure on states to shorten their counts.

The major social media sites are already planning to take steps to block such premature claims from spreading: Facebook will prohibit post-election “victory” ads on election night that are not backed up by independent assessments, and Twitter is preparing to label tweets that, in its words, “claim an election win before it is authoritatively called.” Activists, though, worry that such moves don’t go far enough: A coalition known as Accountable Tech argues that Facebook’s groups function is ripe to be weaponized by bad-faith claims of electoral victory.

North Carolina and Florida, two key bellwethers, both will likely report results relatively quickly on election night itself; early victories for Biden in either or both states will hint that Biden might be the clear winner within a day or so. And while a Trump win in either or both states wouldn’t necessarily foreclose an eventual Biden victory, it would likely mean that the nation would be in for a long period of uncertainty. And the longer the uncertainty, the greater the risk of, well, a lot of other problems cropping up.

Armed groups mobilize

The pandemic has raised numerous concerns this year about the threat from armed right-wing militias—groups more accurately described as domestic terror threats—that are primed to see Democratic or deep-state conspiracies in any results that don’t go their way. How—if at all—this threat manifests itself both during and after the election depends, in part, on where controversy erupts. Michigan and Arizona have particularly active histories with such groups, whereas, for instance, the threat is considered less in North Carolina or Pennsylvania.

Activists on the left have their own “Stopping the Coup” guide floating around online, urging quick action if Trump tries to claim a false victory or shut down an extended vote counting period. “As these scenarios play out it is our job to engage in action that is calibrated with the scale of what is happening. As attempts to defraud the vote count escalates, it is our obligation to shut things down and demand a true reckoning of the democratic process,” the document says.

Once street protests over the outcome of the election begin, they may be hard to turn off—particularly if Trump seizes on the civil unrest for a heavy-handed federal crackdown akin to this summer’s protests in Washington, D.C.

The good news is that state and local officials have strong legal foundations to confront and shut down such groups and gatherings should they choose to do so. A Georgetown University team led by Mary McCord, a former top national security official at the Justice Department, has examined the nation’s anti-militia laws and prepared state-by-state fact sheets about how officials can confront armed groups. “I am seeing bright spots,” she says, as local and state officials have urged calm and emphasized they’re prepared to confront armed groups that may try to intimidate voters at the polls or protest post-election. “The vast majority of Americans don’t want a civil war or violence.”

McCord says her main concern is that under normal circumstances, the nation’s leaders would be the primary voice for calm—but that this year, Trump has already indicated his willingness to stoke violence. “He’s probably going to egg it on, actually,” she says. “I hope people wake up and agree we don’t want to be a failed democracy. Everyone else—athletes, religious leaders, business leaders, state and local leaders—they’ve got to speak up and show that the vast majority of people don’t want armed conflict.”

The Justice Department intervenes

It’s been clear all year that Trump has been trying to pressure Attorney General Bill Barr and the Justice Department to deliver an “October Surprise,” unveiling damaging information in the “unmasking” probe, the Durham investigation into the origins of the Russia investigation or, most recently, investigations of Hunter Biden and his ties to the Ukrainian energy giant Burisma. There are even hints that Trump might fire FBI director Christopher Wray after the election simply for not being willing to help the president’s reelection campaign. The post-election period will offer a fresh opportunity for Barr, who has regularly falsely warned of voter fraud and promulgated odd claims to stoke worries about the legitimacy of elections, such as erroneously saying his department had indicted a man in Texas for falsely voting 1,700 times.

In the first hours after the polls close—or even before polls close—Barr’s Justice Department might seize on real, over-hyped or imagined questions of fraud or voting irregularities to publicly launch investigations that would help Trump build a narrative of an illegitimate election.

This isn’t just partisan anxiety, and it’s not limited to election wonks: Earlier this month, more than 1,000 Justice Department alumni, from both Republican and Democratic administrations, signed an open letter saying they were worried about what Barr might do. “We fear that Attorney General Barr intends to use the DOJ’s vast law enforcement powers to undermine our most fundamental democratic value: free and fair elections,” they wrote. “Given Attorney General Barr’s demonstrated willingness to use the Department to help President Trump politically, the media and the public should view any election-related activity by the DOJ—including any announcement or findings related to the Durham investigation—with appropriate skepticism.”

The actual legal impact of such investigations—whether they led to criminal charges or uncovered legitimate fraud—would likely pale in comparison with the impact on the public debate around the election, as the president and his supporters seized on any steps or allegations leveled by Barr to impugn the outcome of the election.

hACKERS UNDERMINE RESULTs

While officials have warned all year about possible cyberattacks—and clearly Iran and Russia are already engaging in some—the worst-case scenarios of hackers actually changing votes seem unlikely. Instead, the biggest cyber threat is likely from groups pretending that they changed votes. The period of uncertainty after the election provides a ripe opportunity for malign actors—foreign or domestic—to attempt to undermine Americans’ faith in their own democracy. Accomplishing that doesn’t require the hard work of actually changing official vote tallies—which is hard to do and nearly impossible to do at scale given the decentralized nature of the U.S. voting system. Hackers might target news organization or state election websites to make it appear a losing candidate actually won—Russia attempted this very trick in a Ukraine election, planting fake results on the website of Central Election Commission—or might spread disinformation online making it appear voting machines themselves were hacked.

The goal of such actions isn’t to officially change the outcome of the election but to undermine voters’ confidence in the legitimacy of the outcome. Given Trump’s demonstrated proclivity to amplify false claims about the election, trouble could particularly arise from the second- and third-order effects of any such claims—for instance, if Trump, Barr, or state election officials use such disinformation to cast doubt on the election, launch investigations and court challenges, or even refuse to certify election results. Overall, while the low-level mischief meter for the election will be off the charts, the impact from most attacks might be short-lived.

Ballots turn up late

The worrisome and well-documented pandemic woes of the U.S. Postal Service, and the concerns about its Trump megadonor-turned-postmaster general, have turned this venerable agency into a point of worry this year. Nearly three dozen states require absentee ballots to arrive by Election Day—Alabama even requires receipt by noon on Election Day—and the post office is warning that it may take 10 days or more for mail ballots to work their way through the system. It’s all but guaranteed that gobs of ballots will turn up late across the country, perhaps through no fault of voters. More nettlesome questions will arise if ballots turn up in suspicious circumstances, either discarded by postal carriers, hidden in election offices or intercepted by campaigns. Expect court fights around accepting or counting late ballots if an election seems close. If innocently misplaced or nefariously concealed ballots turn up late in an “Election Day receipt” state, voters would have no recourse other than a potentially long-shot court challenge.

A counting collapse

This year could see multiple rounds of problems hit election officials as they try to tally votes, from cyberattacks to the possibility that complex state rules about absentee ballots might invalidate tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of ballots. In South Carolina, there’s already likely to be confusion and ballot challenges around the state’s law that absentee ballots be witnessed; the policy had been suspended, then reinstated by decree of the U.S. Supreme Court, yet absentee ballots were still being sent out with incorrect instructions. In Pennsylvania, media and election officials are racing to educate voters—candidates are even literally posing naked—about the need to put their ballots inside a “secrecy envelope” and warning that under an antiquated law so-called “naked ballots” will be discarded; election officials had tried to suspend the rule, but lost a court fight against the Trump campaign and the Republican National Committee.

The good news is that, despite the fresh logistical concerns of the pandemic, election machinery has in many parts of the country been dramatically improved, tightened and secured since 2016, when Russia’s attack brought fresh attention and resources to election administrators. Many jurisdictions have embraced anew paper ballots, which would make recounts easier and more reliable.

The biggest new challenge to come out of the pandemic will be simply the sheer volume of absentee and mail-in votes likely to land in states that have little experience carrying out large-scale vote-by-mail operations might lead to confusion, slow returns, overwhelmed local officials, and misplaced boxes and bags of ballots. The GOP, meanwhile, is seemingly working to manufacture precisely this type of crisis by preventing local officials from following the best practices of starting to process absentee ballots before Election Day.

Experts have their eyes on Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, crucial swing states that will likely be slow to report results because of their limited ability to process absentee ballots ahead of time. Nevada is mailing all its voters ballots, resulting likely in a slow count, too. There’s a scenario in which, if Trump wins every state he carried in 2016, he will net 260 electoral votes on election night itself and then the nation will settle in for the count—and the fight over the count—in those four remaining battlegrounds.

While the final vote margins are unlikely to be as tight as the 537-vote margin in Florida in 2000, it may take days before anyone feels comfortable declaring even a 10,000 vote or 20,000 vote lead victorious. “Florida 2000 was like trying to track a speeding car and determining whether it was going 72.2 or 72.3 miles per hour—there’s no radar gun in the world precise enough to accurately determine that,” says one Democratic strategist. “This election is like trying to track a car with a stopwatch and a potentially corrupt sheriff.”

Another key fight will likely be around so-called “provisional ballots,” those cast by voters who think they should be registered but aren’t, or, for instance, who show up accidentally at the wrong polling place. Those ballots require additional work by election administrators—and often the voter himself or herself—to verify post-election and may end up being subject to court challenges. Given the certain confusion about relocated and moved polling places for the pandemic—as well as the shockingly higher than expected voter turnout—2020 will surely make heavy use of this mechanism to allow likely eligible voters to participate on Election Day. “There will be more provisional ballots cast this year than normal,” Sherrilyn Ifill, president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund told an Aspen Institute gathering this month. “To the extent that we’ve seen massive voter purges targeted at the African American community, polling place changes targeted at the African-American community and other voter suppression activities, we can expect that the disproportionate number of people who will be casting those provisional ballots will be Black voters.”

It’s entirely possible (perhaps even likely) that the number of disputed or discarded ballots in certain jurisdictions will exceed candidates’ margins of victory or loss. Officials in Pennsylvania, a state Trump won in 2016 by just 44,292 votes, fear the “naked ballot” issue might lead to 100,000 discarded ballots. And that’s likely to affect not just the presidential race, but tight congressional, senate, gubernatorial or legislative races as well.

Legitimate fraud is uncovered

This one is a huge talking point in some circles, but not for most election experts. True fraud in America’s elections is negligible, studies have shown, and even with more use of mail-in ballots it’s effectively impossible to carry out at scale. Nationally, New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice calculated fraud at no more than 0.0025 percent, smaller than almost any possible margin. And despite numerous claims by Trump and Republican officials about increased fraud from vote-by-mail, there’s no evidence that’s true. Quite the contrary: Washington state historically conducts its elections entirely by mail, and its Republican secretary of state, Kim Wyman, says that in 2018 they found 142 fraudulent voting attempts out of 3.2 million ballots—about .004 percent.

However, localized examples of fraud do occur—the most recent example being Republican campaign operatives scheming to deliver a victory in a North Carolina congressional race. Expect any such localized incidents to be seized upon by national voices as systemic indictments.

Vote counters are intimidated or attacked

In the event of contested or disputed vote counts, election protection experts are particularly worried about the reprise of the 2000 “Brooks Brothers riot,” where nicely dressed, khaki-wearing Republican operatives stormed the offices of election administrators in Florida and tried to shut down the counting operation. That protest was a key demonstration of how the Bush campaign outmaneuvered the Gore campaign amid the debacle. “It was a three-pronged effort,” Bush operative Brad Blakeman said in 2018. “It was a court battle. It was a recount organization. And it was also a PR effort because, although the voting effort ended, the campaign never did until there was a definitive and defined winner.”

That then-novel idea of “working the refs” post-election would now be part of the standard playbook in 2020—and officials and experts worry that this year’s political tension and national backdrop might mean threats or acts of violence or targeted online or real-world harassment of election administrators, both at work and at home. “We expect and fear that there will be intimidation of vote counters,” the NAACP’s Ifill told the Aspen Institute audience last month. “Our fear is that this year rather than wearing khakis, they will be strapped with AR-15s. It’s critical to engage with attorneys general, with governors, to prepare to protect the election counters the week after so that we can ensure that all absentee votes are counted.”

Supreme Court challenge that stops a count or ultimately decides the election

Unfortunately, one of the most politically fraught and divisive scenarios that might play out after a close, contested election is also among the most likely—after all, it’s what happened in 2000 to end the counting and hand George W. Bush the presidency. If there are major legal fights post-election and challenges about vote counts, it’s almost certain that such disputes will end up at the doorstep of the Supreme Court. If Amy Coney Barrett is confirmed in the coming days, as the Republican Senate seems set to do, that would mean a decisive 6-3 Republican majority on the court, three of whom are Trump appointees. Trump has already made clear that’s exactly the line-up he wants to be judged by amid any election problems. “I’m counting on them to look at the ballots, definitely,” Trump said.

Any party-line Supreme Court decision that benefited Trump’s candidacy would be viewed with great suspicion by Democrats and Biden voters, further politicizing and polarizing the court, and leaving liberal voters—and perhaps members of Congress—openly questioning the legitimacy of his second term. The key figure to watch here could be Chief Justice John Roberts, who has worked carefully in recent years to preserve the court’s reputation as a neutral arbiter, even if that means siding with the more liberal justices on controversial issues, and would be under immense pressure from both sides in any post-election court cases.

Trump or Biden refuses to accept legitimacy of the results

Trump has attempted to throw all manner of sand into the gears of American democracy—hinting, if he wins, he might run for a third term, refusing to commit to a peaceful transition of power and repeatedly preparing his supporters for a moment where he refuses to concede the election.

His behavior, threats and rants aren’t altogether surprising, given that he’s been so self-conscious and insecure about winning the 2016 election that he’s repeatedly bragged about his Electoral College victory to world leaders and falsely asserted that millions of illegal votes were cast four years ago. Meanwhile, American politics seems uniquely primed to believe that the election results are illegitimate: Politics has been slowly and insidiously poisoned over the past four years by the spread of QAnon, a quasi-religious Republican cult of falsehoods, elaborate and improbable conspiracy theories, and outright absurdity that has so captured the GOP’s base that as many as five Republican congressional candidates have espoused support for it.

Hillary Clinton, for her part, has urged Biden not to be quick to concede a loss either. “Joe Biden should not concede under any circumstances because I think this is going to drag out, and eventually I do believe he will win if we don't give an inch and if we are as focused and relentless as the other side is,” Clinton told Jennifer Palmieri on Showtime's “The Circus” earlier this fall.

Leaders in both parties have tried to downplay fears that the election results may not be accepted. “The winner of the November 3 election will be inaugurated on January 20,” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell tweeted, soon after Trump’s remarks. “There will be an orderly transition just as there has been every four years since 1792.” The obvious wiggle room in McConnell’s framing, though, is that the entire post-election fight will be around just who gets declared—and accepted—as that “winner”?

STATE OR LOCAL OFFICIALS REFUSE TO CERTIFY results

Precise dates vary by state, but sometime in November or early December, each state has an official like the lieutenant governor or secretary of state officially certify the results, the official stamp-of-approval that makes clear who the electors are bound to vote for on December 14. Given enough controversy over voting results, or some nakedly partisan proclivities to usurp the process, it’s possible to foresee a scenario where state officials in, say, Florida, might refuse to officially certify the results—thereby casting the validity of state electors into doubt and potentially robbing a winning candidate of the 270-vote majority necessary to be declared president-elect.

Such a move, though, would hardly take place in a vacuum—it would almost certainly be preceded by a series of cascading problems or controversies upstream in one or more crucial states, and would almost certainly be met with legal challenges. And, it’s ultimately up to Congress to decide which electors to accept, so it’s not even clear that such a move would have a meaningful impact on the outcome.

However, how and where problems at this level would be resolved—either in court or by the House of Representatives—would push into uncharted territory for the U.S. electoral system.

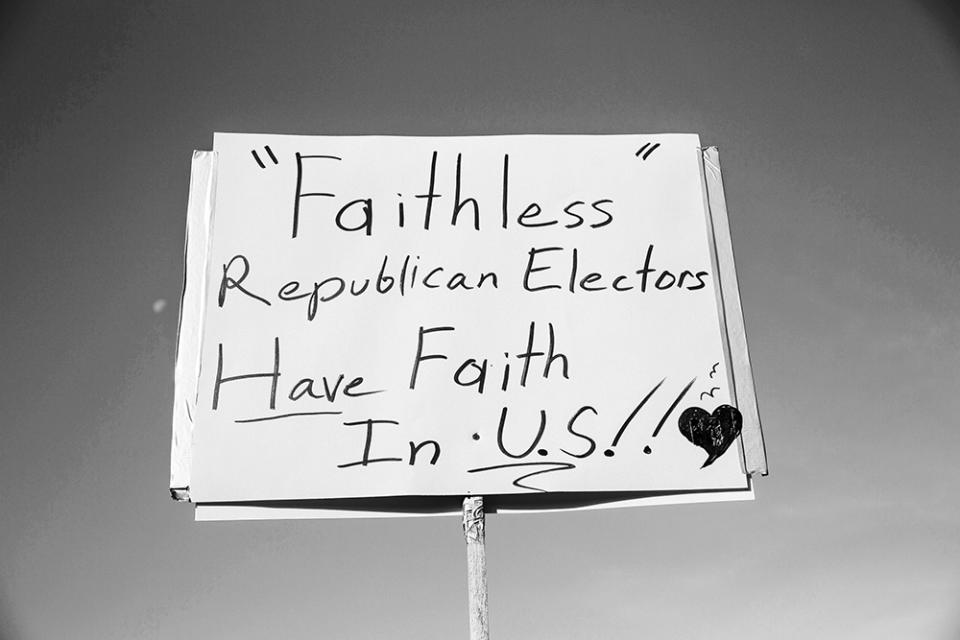

Electors revolt or are replaced

There’s probably no greater trope of political fan fiction in the U.S. than idea of a last-minute curve ball coming from the antiquated practices of the Electoral College, which boils the national election down to 538 Americans officially voting on the nation’s president on December 14. Nearly every election cycle sees stories like this oversold Fortune headline from Monday: “The election night winner could get dumped by faithless electors”—people who while pledged to one candidate vote for someone else, either out of conscience or protest. (Certain states in recent years have taken steps to raise penalties for electors who vote against their bound candidate, but they remain so minor that they’re effectively meaningless.)

Yes, technically it’s true that the electors could decide on their own to elect Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson president in December, but there’s no real reason to imagine a broad uprising by electors. While electors, in protest or by accident, have voted for other candidates not on the general election ballot—in 2016, for instance, a few cast meaningless votes for noncandidates like Bernie Sanders, John Kasich and Colin Powell—only one elector has ever switched to cast a vote for the opposing presidential nominee.

This year, though, there’s a potential different twist in the Electoral College: The threat of Republican legislatures replacing Democratic electors before they have a chance to vote at all. In an article earlier this fall in the Atlantic, Barton Gellman reported that Republican operatives and the Trump campaign are “discussing contingency plans to bypass election results and appoint loyal electors in battleground states where Republicans hold the legislative majority. With a justification based on claims of rampant fraud, Trump would ask state legislators to set aside the popular vote and exercise their power to choose a slate of electors directly.” Those loyal electors, chosen by the state legislature, would then presumably vote for Trump over Biden, actual results be damned.

Any such plan, however far-fetched and damaging to democracy, would hinge on (a) Trump’s losing, (b) his or the GOP’s casting enough doubt about the outcome and real vote totals that state legislators would feel OK enacting what would be a constitutional coup, and (c) the validity of those electors sustaining an inevitable court and congressional challenge. Plus, in some states, the governor might appoint his or her own set of electors, which could end up meaning that certain states present competing slates of electors to Congress on January 6. Credentials of competing elector slates would ultimately be judged by Congress, which would choose which set of votes to accept—although the process for such vetting is unclear. Some states have their own rules for how to handle a crisis like this, which themselves can be gamed: North Carolina, for instance, says that in the event of “dueling electors,” the slate chosen by the governor should be considered the legitimate one. (Not scared enough yet? A Carnegie scholar sketched out how such a plot would unfold in practice.)

It’s not clear that such a legislative end run would be allowed legally, as the law calls for electors to be chosen ahead of the national vote itself—making any post-election changes legally suspect. And the Supreme Court itself has already said in an unrelated case this year that “legislatures no longer play a role” in choosing electors, which would make the court battle to sustain a legislature overruling the popular vote an uphill battle in the extreme.

The winner is incapacitated or dies

The president’s Covid-19 diagnosis this fall immediately raised questions about the process for changing electoral horses midstream—and the advanced age of both candidates makes health threats an ongoing concern.

The question of what happens if the winning candidate dies or is incapacitated hinges on when it occurs: If it’s before December 14, when the Electoral College vote officially occurs, party rules for the Democrats and Republicans guide the members of the Republican National Committee or Democratic National Committee through officially recommending a substitute who, with some complication and maneuvering, could then be officially chosen by the Electoral College.

If such an incident unfolded between December 14 and January 6, when Congress officially accepts and certifies the election, the presidential election would go to Congress itself. And if the official president-elect can’t be sworn in on January 20, the vice president-elect would simply be sworn in instead.

The U.S. has never had a presidential winner expire midcount, but it has had a losing candidate die: In 1872, Horace Greeley died on November 29, after losing the election to Ulysses S. Grant but before the Electoral College officially voted; in the end, individual electors chose to cast the 66 electoral votes that Greeley had won for his vice presidential candidate, Benjamin Gratz Brown, as well as three other minor-party candidates, instead.

Congress chooses a president

Many aspects of the election would have had to go sideways before Congress get involved in any more than a ceremonial way, but the 12th Amendment outlines a narrow set of circumstances in which the House of Representatives and Senate end up choosing a presidential victor if there’s no majority in the Electoral College or, as mentioned above, the victor of the Electoral College dies before Congress officially certifies the vote on January 6. In a narrow or disputed election this year, the Electoral College could offer a 269-269 tie or disputes among electors might deny either candidate a majority.

The congressional election of a president is a process that’s known as a “contingent election,” and it hasn’t been used for the presidency since 1825. In the scenario of a “contingent election,” the House votes for the president and the Senate chooses a vice president, meaning it’s entirely possible, if the opposing parties each control one chamber of Congress, for the two to be of opposing parties.

In the House, each state gets a single vote—meaning that the presidency would likely fall to whichever party controls the majority of state delegations come the new Congress. (The District of Columbia, which normally gets three electoral votes, would be sidelined and cut out of the process in the House.) Nancy Pelosi is already laying the groundwork for such a fight: Right now, Democrats are outnumbered 22 states to 26; Pennsylvania’s delegation is equally split, and Michigan’s delegation is complicated by the wild card of independent, and Trump, foe Justin Amash. “We’re trying to win every seat in America, but there are obviously some places where a congressional district is even more important than just getting the member into the U.S. House of Representatives,” Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), a constitutional lawyer, told POLITICO last month. (For the true constitutional sci-fi fans, there are even proposals afoot about how Nancy Pelosi could selectively challenge certain incoming representatives to the 117th Congress in January to ensure victory in a contingent election.)

If the election looks likely to come down to the House in January, pay special attention to the outcome of state congressional races where Democrats currently hold just a one- or two-seat advantage—places like Arizona, Colorado, Iowa, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada and New Hampshire—as well as Florida and Wisconsin, where Republicans currently hold a narrow lead in the state’s delegation. Pennsylvania is already expected to become a majority Democratic delegation in November, and if Democrats manage to flip the sole congressional seat in either Alaska or Montana, those single at-large seats would secure an entire “delegation” vote in any continent election. A Democratic wave at the congressional level might prove decisive come January 6.

Under even wilder scenarios, if the House were to deadlock for a period of time on a presidential vote, the vice president-elect chosen by the Senate might become “acting president” for a period of time after January 20.

Trump refuses to leave office

As much as catastrophists and nervous Democrats skitter about the possibility of a defeated Trump refusing to leave office, the reality is that even if he proves a sore loser, the worst-case scenarios seem vanishingly unlikely.

Presidential power shifts automatically under the Constitution at noon on January 20—it’s not like Trump has to sign a resignation letter or turn over the keys to the presidential limo—and there’s nothing that Trump could do to delay that or prevent his successor from then utilizing those powers. If he loses, as of noon on January 20, Trump would be trespassing at the White House, subject to arrest and removal by the Secret Service the same as anyone who jumps the Pennsylvania Avenue fence.

Given the U.S.’s long, proud history of peaceful transitions of power and civilian control of the military, it’s hard to imagine the scenario in which a president duly elected by 270 electors and certified by Congress who takes office on January 20 has to have U.S. marshals and the 82nd Airborne fight through rings of bikers and sheriffs and physically carry Donald, Melania, Jared and Ivanka out of the West Wing and dump them in Lafayette Park.

Whether a defeated Trump makes it difficult for Biden on his way out the door—or whether a departed Trump moves into his landmark hotel a few blocks down Pennsylvania Avenue and attempts to set up a pretend shadow MAGA government-in-exile? That’s another question entirely.