Guiding African Wildlife Through Global Warming

Jessica Arriens is a public affairs specialist for the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

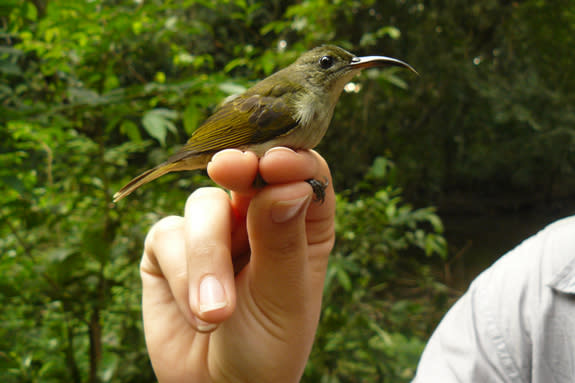

The Congo basin is an unruly ribbon of tropical forest, more than a million square miles spanning six countries in Central Africa, running inward along the equator from the continent's western coast. It is the second-largest contiguous tropical forest in the world. The basin is home to the classics of African wildlife — chimpanzees , elephants , gorillas — along with thousands of other less well-known species: pale, long-legged golden puddle frogs, hook-beaked Olive Sunbirds, and squat blue duikers, which look like shrunken antelopes.

This wealth of flora and fauna, much of it native to the region, is enough to qualify the Congo basin as a biodiversity hotspot: a biologically rich area threatened by outside forces. In Central Africa, those forces include deforestation, climate change, hunting and more.

The region is "so enriched with life," says Mary "Katy" Gonder, a Drexel University biologist and one of the lead researchers on the Central African Biodiversity Alliance (CABA). "And that life is precarious right now."

Funded in part by NSF, the alliance is an international partnership of scientists, students and policy makers working to build a framework to conserve biodiversity in Central Africa. The partnership spans three continents, and includes researchers from the United States, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Germany and the United Kingdom.

To build a conservation framework, the researchers are using genomic tools and environmental modeling to identify areas worth conserving: sweet spots that both maximize the pattern of biodiversity and the processes that produce and maintain it.

CABA is focusing on nine different species, a broad range that includes plants (a flowering plant called arrow root), invertebrates (the light bush brown, a forest butterfly) and vertebrates. Researchers are mapping the variation of all these species — both genetic and phenotypic, or apparent — and analyzing how such variation, when combined with other qualities like evolutionary adaption and land connectivity, can help species thrive.

The end goal is to find spaces in the Congo basin where species have plenty of adaptive variation, prioritize those spaces, and work with policy makers to ensure they are conserved.

All research is rooted in the region's socioeconomic realities. From the start, CABA members have met with government officials in the region, to ensure policy makers are both informed about the research and play a role shaping it. Training future scientists and engineers is also a big piece of the project. The alliance has held professional development workshops for students and scientists — both American and African — to discuss everything from experiment design and statistics to grant writing and leadership. CABA members have also helped facilitate workshops for women in science, through COACh (Committee on the Advancement of Women Chemists) International.

Exposing American students to globally focused research, partnerships and — for most of them — a completely foreign part of the world is another "great benefit" of the project, says Nicola Anthony, a biologist at the University of New Orleans and another lead CABA scientist. "Even if they don't end up in science for a career, they'll be much better global citizens as a result of this."

CABA's "breadth and effectiveness are very impressive," says Lara Campbell, a program officer in NSF's International Science and Engineering section, which funds PIRE. "They are producing a strong cadre of American and African scientists prepared to address the many future challenges of climate change impacts on ecosystems."

NSF funding for CABA comes through the Partnerships in International Research and Education (PIRE) program, which supports innovative, international research and education collaborations. PIRE projects stimulate scientific discovery and strengthen U.S. universities; the projects forge worldwide partnerships and help train a globally engaged scientific and engineering workforce. CABA also receives funding from the Arcus Foundation and the Exxon Mobil Foundation.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.