Guilty without bail until proven innocent in Alabama? Aniah's Law full of flaws

Alabama just passed a law that could send thousands of innocent people to jail before they stand trial. Can they do that? Under Aniah’s Law, it seems likely.

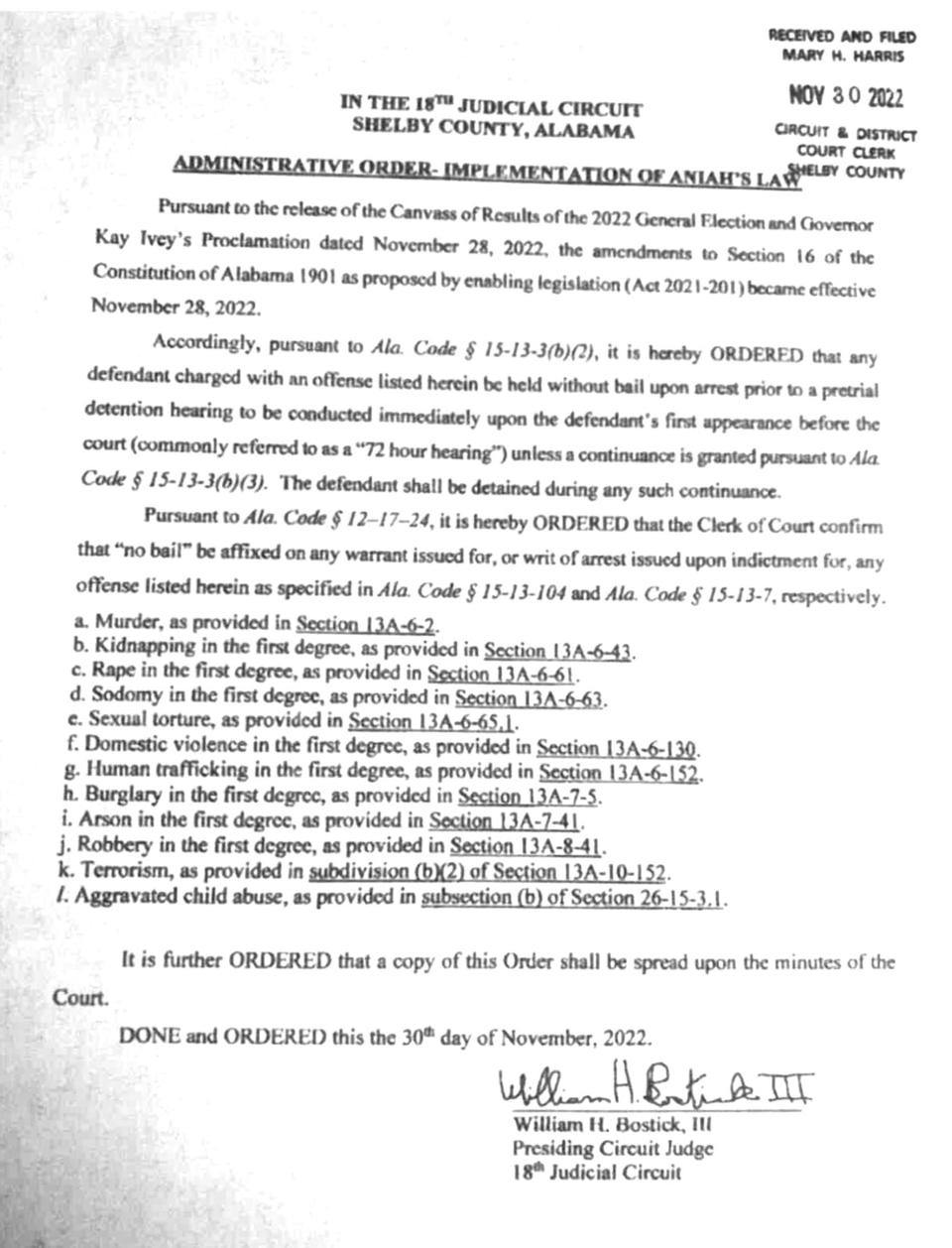

Aniah’s Law was passed this November to expand the types of criminal charges ineligible for pre-trial bail in Alabama. While many consider this a win for cracking down on crime, most people don’t realize this law will cause more public harm than good. I am calling on lawmakers to revisit the language because as Aniah’s Law is currently written, it boldly erodes a foundational tenet of American justice — we are “innocent until proven guilty.”

Before Aniah’s Law, every Alabamian had a constitutional right to bail. When someone was arrested on a criminal charge other than capital murder, bail was immediately set by a magistrate. If the arrestee could afford to post bail, they were released until required to return to court. If they could not, they waited in jail for a 72-hour hearing, where a judge weighed a number of factors to review the amount and conditions of the bail. Bail was not set as a punishment, but rather an assurance the person would return to court on their pending charges. This is how Alabama, along with 18 other states, always determined bail, until now.

Aniah’s Law upends this process. The law is named for Aniah Blanchard, a woman tragically kidnapped and murdered in late 2019. In her case, the accused murderer was previously charged with another kidnapping, free at the time of her death on a $295,000 bond. The new law was drafted on the premise that this outcome was avoidable, had the accused not been free on bail. It includes specific additional crimes that are no longer considered bailable, but it sweeps too broadly.

Now, when someone is arrested simply on an allegation of any of the law’s enumerated crimes, they will be held in jail for a minimum of 72 hours before they get a chance for a hearing where both sides may present evidence and witnesses. While that may sound fair in theory, in practice it is quite unbalanced. When law enforcement charges someone with a crime, they generally start investigating the allegation, gathering witnesses and evidence right away. In contrast, the incarcerated person is often not even told the details of the allegation until their preliminary hearing, which can take place weeks after their arrest. Most are not assigned an attorney or given a copy of the state’s evidence against them until weeks or even months later.

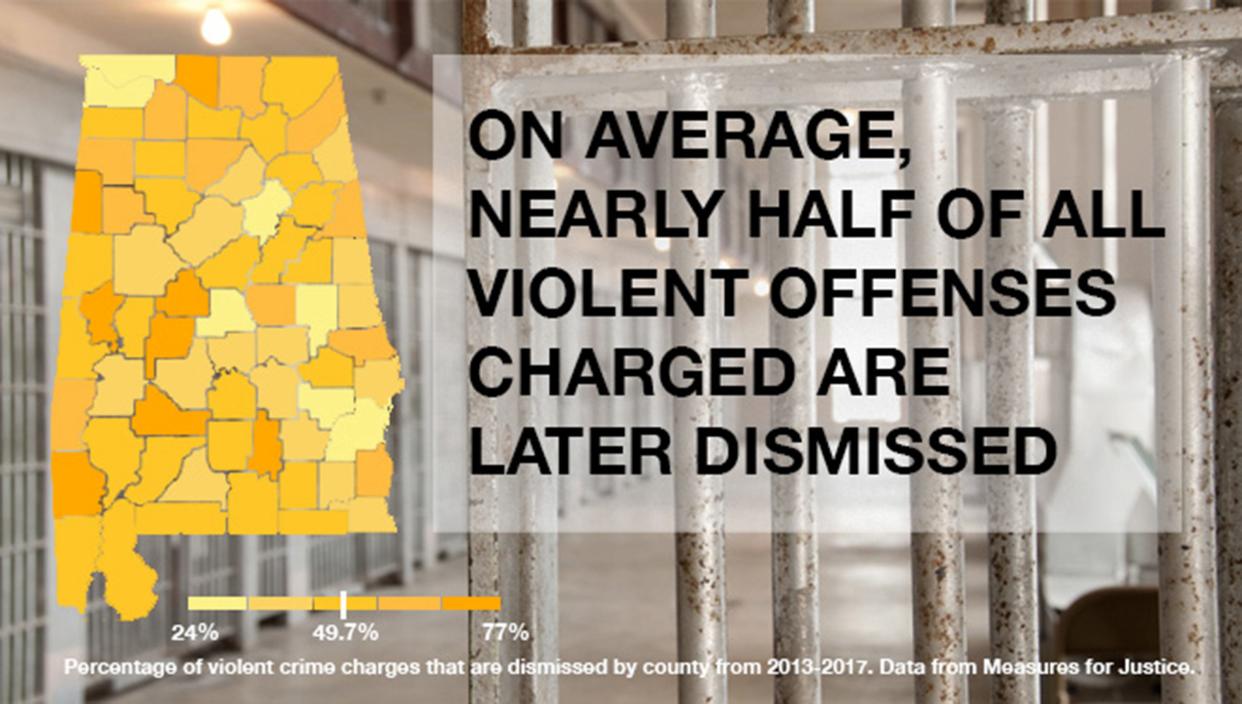

It is a falsehood to expect an incarcerated person to meaningfully gather witnesses, evidence, and everything they need to defend themselves in less than 72 hours. The right to bail and the presumption of innocence are critical to even the playing field for the accused, especially when probable cause to arrest can be based on a single unsupported allegation. Aniah’s law grossly skews this delicate balance. Lawmakers should consider amending the new list of non-bailable crimes, and at the very least should add provisions that uphold the rights of the accused. Although adopting this law bumps Alabama into the company of 22 other states which also enumerate specific non-bailable crimes, few include burglary or robbery as Alabama now does, for example. These crimes, in particular, can have a low threshold for being charged. In fact, according to the non-profit Measures for Justice, approximately half of Alabamians accused of these types of violent crimes are later released without a conviction. If cars had the same 50% failure rate, no one would drive them.

A defense attorney from Northport, AL with over 40 years of experience, recounts how his clients could be negatively impacted by Aniah's Law. Take for example, Mr. Hood, from Tuscaloosa County, who was charged with robbery in the first degree in March 2016. He was found to be intellectually disabled and while awaiting trial was released to the care of his grandmother. He was able to seek treatment for his disability — a luxury he would not have been afforded had he been forced to remain in jail. Mr. Hood's case was ultimately dismissed this year, despite the ADA moving for dismissal in 2019 when the evidence from the case originally fell apart. Under Aniah's Law, Mr. Hood could have served those six years continuously in prison rather than receiving treatment and care from his family.

Additionally, where other states include a specific list of non-bailable crimes, there are provisions to alleviate the harm imposed on the accused. For example, Michigan and Colorado include a requirement for a trial within 90 days when bail is not offered. Many other states, including Texas, require judges to consider previous convictions in their decision to withhold bail. Aniah’s Law does not include these essential provisions. Its particularities may put Alabama in a category of its own with the harshest bail law in the country, teetering on the cusp of cruel and unusual.

The human toll of this law is yet to be seen, but instead of increasing public safety as intended, it will very likely have the opposite effect. Innocent people erroneously charged with crimes will be forced into vulnerable situations and confined in dangerous, overcrowded jails. Southern Poverty Law Center Policy Director Jerome Dees points out how this snowballs. “You’re stuck in jail, you’re no longer able to work. If you have children, it brings up custody issues. It totally destroys the family and the community around you only for you 18 months to two years later to finally be determined innocent as you had been all along,” says Dees.

Defense attorney Leroy Maxwell of Birmingham elaborates on this and points out that bail can include conditions to actually help combat the negative effects. He says that removing bail as an option is not the right direction if we want to prevent more crime. “When people accused of crimes are immediately incarcerated instead of returning to society while awaiting trial, they often lose their jobs, their housing, not to mention the toll it takes on families,” says Mr. Maxwell. “Offering bail means judges can apply conditions to release that include maintaining a job, complying with rehabilitative services, and receiving skills training. If we want to make sure what happened to Aniah doesn't happen to others, these are the types of social structures that will help us get there. Removing the option for bond and locking people accused of crimes in jail with convicted violent offenders will ultimately put those folks in much worse positions when they are later found to be innocent.”

Our prison system is already beyond capacity and this new amendment will exacerbate its failures, especially as Alabama courts are facing long backlogs in criminal cases due to the pandemic. The repercussions of increased mass incarceration will be felt beyond those locked up, extending to their children, families, and society at large.

We do not yet know how some of the particularities of this law will be interpreted, but courts are already starting to issue orders to hold defendants without bail prior to their first court appearance. There is an urgent need to address the effect this is about to have on our communities. I implore Alabama’s lawmakers to amend Aniah’s Law immediately, to include more humane provisions that afford those awaiting trial a safer, more dignified existence that minimizes harm. As written, it erodes the presumption of innocence, and makes a mockery of our right to due process.

Tara Eisenberg is currently studying criminal law and environmental justice at CUNY Law School. She previously worked in public policy and urban planning.

This article originally appeared on Montgomery Advertiser: Guilty & no bail until proven innocent in Alabama? Aniah's Law flawed