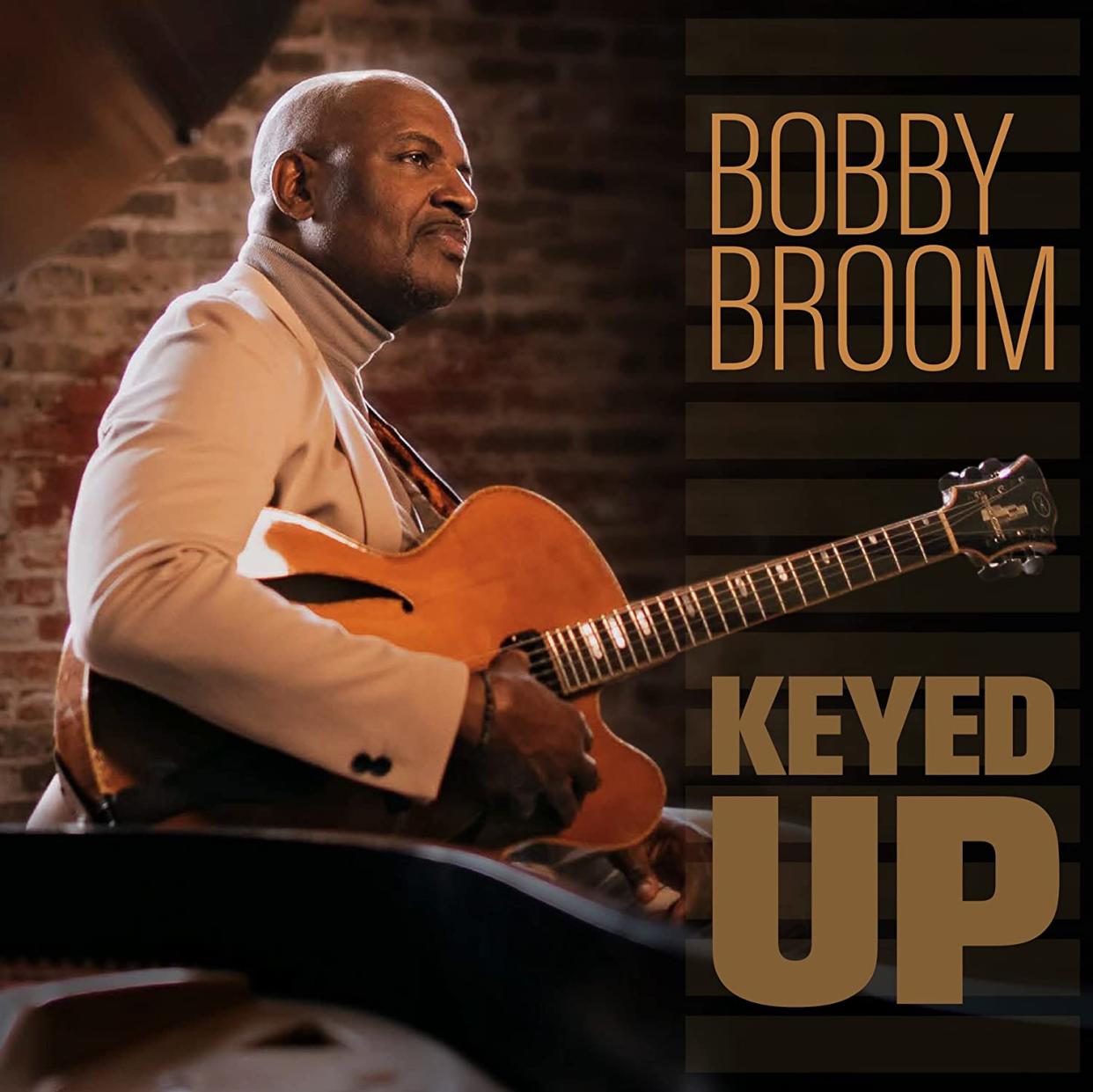

Guitarist Bobby Broom pays homage to pianists on 'Keyed Up'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The first time I believe I ever heard — or heard of — Bobby Broom took place in Jesse Hall on April 24, 1987.

That was the night the “Saxophone Colossus,” Sonny Rollins, made his first and only appearance here. Broom was the group’s guitarist. I’ve followed what’s become an extensive career since, having seen him in Chicago, where the New York City native has been a fixture — and one of the city’s leading musical voices — for years.

“Every modern jazz guitarist in Chicago is indebted to Bobby Broom,” said Jeff Parker, himself an accomplished guitarist whose Columbia appearances include one with organist Joey DeFrancesco and another with drummer-percussionist Makaya McCraven.

“He opened up the doors of perception for us all — he’s a master jazz stylist and a musical visionary."

Although often associated with leading his organ trio, Broom’s experience is as wide as it is vast. It includes not only a six-year stint with Rollins, but also a similarly lengthy stay with Dr. John. Broom, in a news release, said, “For me, that was a lesson in the origins of rock and roll.”

Some, but certainly not all, the guitarist’s long-running experiences incorporate being a part of Kenny Burrell’s guitar band; a stay with Miles Davis; as well as his work with pianist Al Haig. Of course, there’s a plethora of engagements with, at the time, fellow Chicagoans such as saxophonist Eric Alexander and organist Charles Earland.

When thinking of Broom, you have to think of versatility. He truly does cover the musical waterfront.

Broom’s first release dates to 1981. As you visit his 40-year discography, you come across everything from interpretations of Thelonious Monk to Stevie Wonder, show tunes and more. He recorded for more commercially-oriented labels such as GRP Records as well as for staunch labels such as Criss Cross.

However, Broom is not really known for working with pianists per se, though he’s certainly keenly aware of and been influenced by numerous keyboardists, something he chose to zoom in on for his soon-to-be-released title “Keyed Up” (Steele Records).

The session, where he’s joined by bassist Dennis Carroll and drummer Kobie Watkins, two of his regular associates, is augmented with fluid keyboardist Justin Dillard, a younger Chicagoan who primarily plays acoustic piano but also mixes in the Hammond SKX; given Broom’s penchant for the organ, that’s certainly logical.

“Keyed Up,” which features 10 selections, including two takes of McCoy Tyner’s “Blues On The Corner,” amounts to a personal musical statement. It’s Broom’s way of recognizing and “giving some” not to the drummer, but rather to a selection of pianists who either left direct impressions upon him or to other seminal pianists that played an important role in his overall jazz development.

Some of those acknowledged here don’t necessarily surprise. There is a reading of Errol Garner’s classic standard “Misty”; Bud Powell’s quick-bebop-tempoed “Hallucinations (Budo)”; the even more high-powered version of Horace Silver’s “Quicksilver”; Chick Corea’s “Humpty Dumpty”; and Herbie Hancock’s riff-filled “Driftin’.”

While these works might be familiar to most people along with the aforementioned “Blues On The Corner” takes, each of these interpretations stand on their own. This is a tight, quality-filled ensemble that knows, behind Broom’s leadership, what they want to do with these pieces — and how to deliver them in the way they wish.

Still I have to admit what attracted me, at least in part, to “Keyed Up” is the guitarist’s inclusion of pianist James Williams, who happens to be one of my personal jazz heroes. Incorporating Williams’ “Soulful Bill,” composed for his fellow Memphian, the multi-instrumentalist Bill Easley, pleasantly surprised me. Then again, Williams taking an interest in, recognizing and serving almost as a talent scout for artists who demonstrate early proficiency is not that far of a stretch.

“James (Williams) was one of my ardent champions and supporters,” writes Broom in his liner notes. “According to others, he often sang my praises, and hired me to play in his ensemble on occasion. ‘Soulful Bill’ was a tune of his that we used to play in the 1980s and ‘90s, and one that I played in the very early days of my trio but never recorded. I thought it perfect for this occasion.”

It is a bit intriguing that Broom also includes a Mulgrew Miller piece. Miller and Williams were roommates at Memphis State University, now the University of Memphis, and would remain friends till death, each passing prematurely: Williams at 53 in 2004, Miller at 57 in 2013. I could swear in the midst of Miller’s “Second Thoughts,” a kind of soft lilting ballad, I kept hearing Broom quote “Alter Ego,” one of Williams’ best-known pieces.

Not that it matters. What’s poignant here is Broom, a guitarist, taking the time to investigate and conjure up a varied program comprised of important pianists and pianists important to him.

Jon W. Poses is executive director of the “We Always Swing” Jazz Series. Reach him at jazznbsbl@socket.net.

This article originally appeared on Columbia Daily Tribune: Guitarist Bobby Broom pays homage to pianists on 'Keyed Up'