Gypsy Rose Blanchard Was a Medical Mystery. A Failure of Science Made Her a Murderer.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

This story is a collaboration with PopularMechanics.com.

Lately, you’ve probably seen Gypsy Rose Blanchard all over magazine covers, daytime talk shows, and social media feeds. But she isn’t newly renowned for, say, being a burgeoning pop star. She hasn’t achieved some great feat of athleticism or broken out in a star-making role in a prestige movie. The inciting incident that put the 32-year-old on America’s radar, drew millions of followers to her TikTok account, prompted Lifetime to rush out a multi-part docuseries, and sent Penguin Random House to snap up her memoir isn’t a traditional rags-to-riches chapter in a rise-to-fame story.

Gypsy Rose Blanchard is famous for being a convicted murderer.

Of course, despite being convicted of second-degree murder for the death of her mother, Dee Dee Blanchard, and serving 8 years of her 10-year sentence for the charge, to which she pleaded guilty, Blanchard recently stated that she doesn’t agree with that label. As she recently admitted on The Viall Files podcast, “When they say I’m a murderer, I don’t identify as that.”

And Blanchard isn’t the only person who feels that way.

Neither Blanchard, nor her many fans and defenders, deny that she was involved in her mother’s death. The official story of the murder plot itself, according to Biography.com’s previous reporting, is not in dispute:

“[Gypsy] joined a Christian dating site, where she met Nicholas Godejohn. She told him the truth about her mother’s actions and ended up asking him to kill Dee Dee so they could be together. In June 2015, he came to her house and stabbed Dee Dee while Gypsy waited, ears covered, in the bathroom.”

At first blush, the planned murder of Dee Dee Blanchard might have seemed no different than other famed cases of familicide, be it the Twilight Killers, the Richardson Family murders, or perhaps the most famous case, the Starkweather homicides.

But it was the revelations regarding Gypsy Rose’s “truth about her mother’s actions” that shocked—and elicited sympathy from—the public. Understanding the circumstances, and the systemic failures, that led to Dee Dee’s murder requires grappling with a complex form of child abuse that goes by several names, including the most common in our contemporary media: Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy.

What Is Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy?

In the foreword to Sickened: The True Story of a Lost Childhood, a 2003 memoir by author Julie Gregory, Dr. Mark Feldman begins by noting that, “Munchausen by Proxy may be the single most complex—and lethal—form of maltreatment known today.” Feldman, a Distinguished Life Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association who has written several books on the subject, explains Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy (MBP) in his foreword as:

“It is formally defined as the falsification or induction of physical and/or emotional illness by a caretaker of a dependent person. In most cases, the perpetrator is a mother and the victim is her own child.”

Feldman wrote that foreword, which also notes that most cases of MBP “go unreported—indeed, entirely undetected—due to the covert nature of the maltreatment,” more than a decade before Dee Dee Blanchard’s murder, and before the public became fascinated with Gypsy Rose through the 2017 documentary Mommy Dead and Dearest (in which Feldman appears as an expert).

Gypsy Rose, who was born in 1991, was a baby when Dee Dee claimed her daughter had sleep apnea. “When Gypsy was 8 years old,” we previously reported, “Dee Dee described her as suffering from leukemia and muscular dystrophy and said she required a wheelchair and feeding tube. The list of medical problems that Dee Dee related about her daughter would go on to include seizures, asthma, and hearing and visual impairments.”

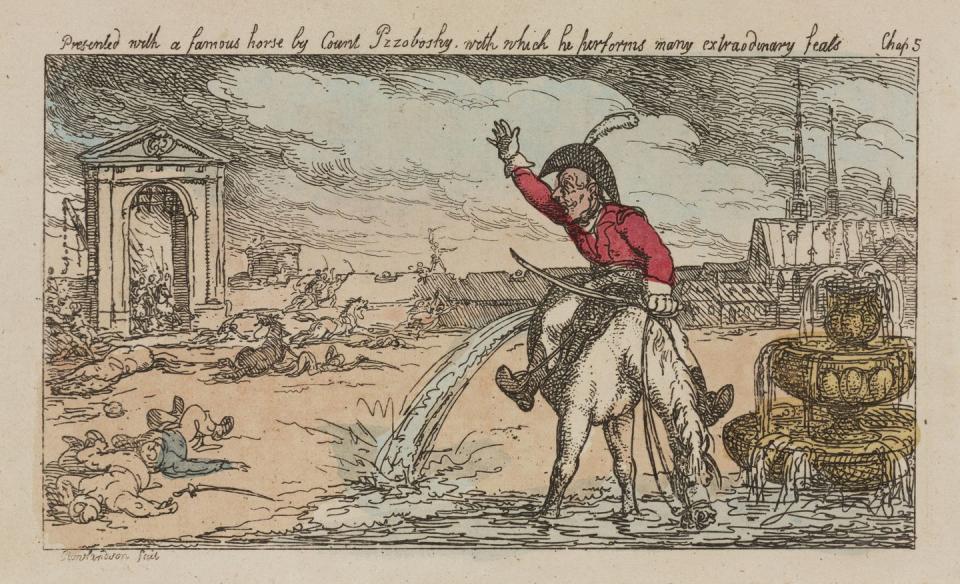

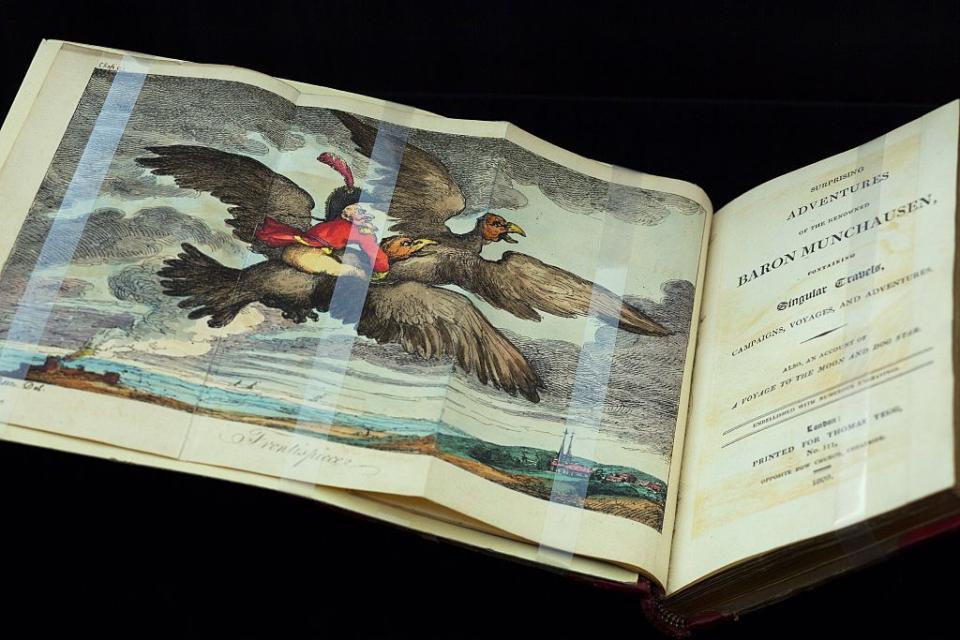

Although MBP, officially known as Factitious disorder imposed on another, is far more in the vernacular today than it had been when Gregory and Blanchard were being subjected to their respected abuses, it’s not as though it was unknown. The term “Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy” was first used by Roy Meadow in The Lancet in 1977 to describe “parents who, by falsification, caused their children innumerable harmful hospital procedures” as “a sort of Munchausen Syndrome by proxy.”

In choosing to incorporate the words “Munchausen Syndrome” in his labeling of this specific form of child abuse, Meadow was evoking the more well-known form of fictitious illness, Munchausen Syndrome.

First identified by Richard Asher in 1951, Munchausen Syndrome was coined to describe individuals who either fabricate medical conditions or go so far as to commit acts of self-harm to induce symptoms of real illnesses. In trying to define this issue, Asher wrote:

“Here is described a common syndrome which most doctors have seen, but about which little has been written. Like the famous Baron von Munchausen, the persons affected have always travelled widely; and their stories, like those attributed to him, are both dramatic and untruthful. Accordingly the syndrome is respectfully dedicated to the Baron, and named after him.”

Asher chose to name his described syndrome after the “famous” Baron von Munchausen, specifically the fictional German nobleman character created by writer Rudolf Erich Raspe, not the real Hieronymus Karl Friedrich von Münchhausen that the character was lampooning. But by the end of the 20th century, the syndrome itself was easily more well-known than its namesake. For example, on April 19, 1983, more than 9 million viewers tuned in to an episode of the NBC medical drama St. Elsewhere titled, “Baron von Munchausen,” wherein a patient fabricated their illnesses for attention.

What Do We Get Wrong About Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy?

It’s easy to see why a syndrome that involves fictitious ailments would be fodder for many fiction writers in the 20th century, just as it’s easy to understand why Asher, and therefore Meadow, sought to associate their discovered syndromes with the fantastical fabulist namesake of Raspe’s novel. But in the flurry of all that fiction, we can lose sight of the very real harm that can be wrought upon the children treated for those fictitious diseases.

Consider again what Gypsy Rose Blanchard endured at the hands of her mother in the name of “caregiving,” from Biography.com’s earlier reporting:

“Gypsy was prescribed a litany of medications and had to sleep using a breathing machine. She also went through multiple surgeries, including procedures on her eyes and removal of her salivary glands. When Gypsy’s teeth rotted—perhaps due to her medications, missing salivary glands, or neglect—they were pulled out.”

These gruesome images of neglect and unnecessary surgeries tend to fall by the wayside of our imaginations, as a term like Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy conjures images of wild-eyed patients on TV shows and fanciful Barons. That’s why many experts tend to favor other terms that more directly address the fallout of this syndrome, including terms like Medical Child Abuse (MCA) or Fabricated or Induced Illness by Carers (FII).

“When being interviewed about this form of abuse, I tend to use whatever term the interviewer uses, rather than drag them through the nomenclature debate,” Feldman tells Popular Mechanics. “By far, the term ‘MBP’ is best known among the general public and even among health care professionals, so I use it freely. But it is opaque. It tells you nothing about the maltreatment itself.”

Feldman says he prefers to use Medical Child Abuse instead of Munchausen by Proxy. “MCA has drawbacks, for sure,” he says, “... but emphasizes that this is a form of abuse, not a mental illness that someone ‘suffers from’ or ‘has’; that it involves the world of health care; that children are usual victims; and that it is very clearly a type of abuse.”

The use of MBP ultimately leads to one of the biggest public misunderstandings about the syndrome, Feldman says: “that MBP is a mental illness or personality defect.”

“That’s why judges all over the country are ordering psychological assessments to ‘see’ if someone has Munchausen by Proxy,” he says. “It is like ordering psychological testing to see if a father ‘has sexual abuse’ or ‘suffers from sexual abuse.’ The MBP term should always be followed by the word ‘abuse’ when it is used, but I still prefer MCA, which is so explicitly a form of maltreatment and nothing else.”

How Medical Science Fails Victims of Medical Child Abuse

Perpetrators of Medical Child Abuse can find many ways to get medical treatments for their children in order to garner sympathy for themselves. As was described in The Prison Confessions of Gypsy Rose Blanchard, Dee Dee Blanchard had “a stolen prescription pad, which allowed Dee Dee to abuse Gypsy without even needing to rely on a doctor.” Dee Dee would also falsify documents pertaining to her daughter’s age.

But experts say the most common way these abusers manage to subject their children to needless treatments is by merely working within the medical system and convincing medical professionals to do what they asked. Dee Dee took advantage of situations, like claiming Gypsy’s medical documentation was lost in Hurricane Katrina in order to convince doctors to take her word for it and using her nursing training to describe, or even elicit, symptoms in her daughter.

Persuasion, in cases of MCA, can go a long way. As Julie Gregory describes in her memoir, her own mother had “convinced a cardiologist” to make Julie undergo open heart surgery.

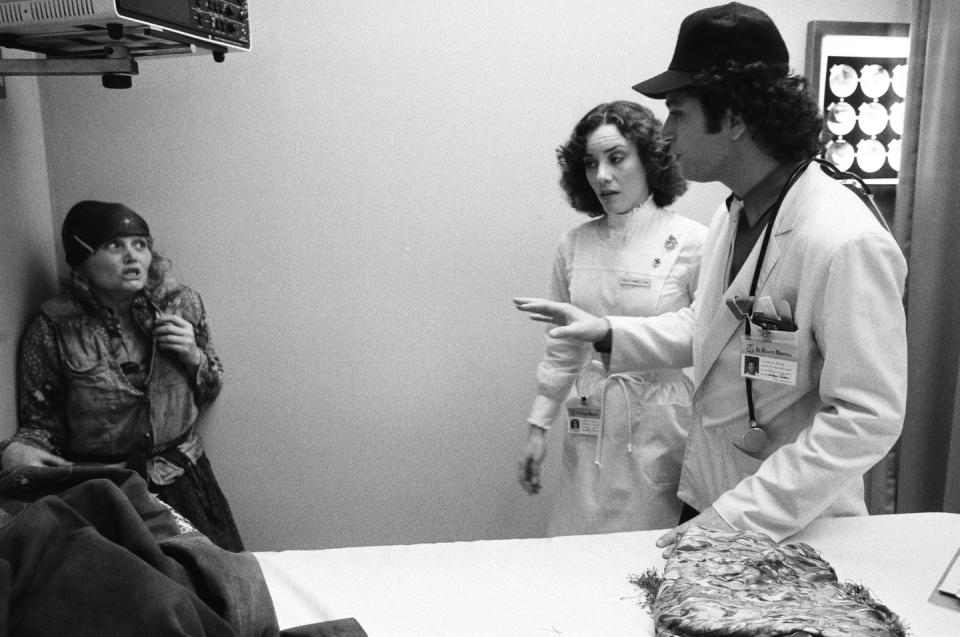

How do medical professionals manage to so often miss MCA and even allow themselves to be accessories to it? “The period between the start of abuse and its discovery can be long—if it ever occurs at all,” Feldman tells PopMech. “Several barriers can delay the timely detection and confirmation of MCA,” he says, including—but not limited to—these:

Failure to even consider MCA as a possible diagnosis.

A lack of knowledge about MCA on the part of health care professionals.

The tendency of the provider to believe the history the caregiver provides, even when it seems dubious. “This is especially true if the provider hasn’t reviewed any health records or spoken to prior health care professionals,” says Feldman.

The ability of the caregiver to present a highly persuasive and compelling history. “Doctors are taught throughout their training to rely on what patients and family members say,” Feldman says, “and this contributes to their often being unduly credulous.”

The involvement of several providers, often in different settings and sometimes different cities, regions, or even countries. “This is called doctor-shopping or hospital-shopping, and providers may not know anything about it because of the lack in the U.S. of a centralized health care database for patients,” says Feldman.

Fear of making a false accusation (or even a true one) and its subsequent legal repercussions. Feldman says perpetrators routinely run to the media, government officials, and crusading lawyers when an accusation arises, even though doctors don’t make the final decision about the form the child protection will take—judges do.

A lack of collaboration or poor relationships among medical, legal, and child protection agencies, along with providers’ reluctance to become involved in a child protective case. “Many of them don’t make reports to the authorities despite the laws in all 50 states that mandate reports of reasonable suspicions of abuse—even without definitive proof,” says Feldman.

Reluctance to admit the possibility that the professionals have been fooled. “They avoid thinking about the fact that their treatments—which can include surgery—were unwarranted,” he says.

Several of these barriers can be seen in the Gypsy Rose Blanchard case. Biography.com previously pointed to this instance:

“When Gypsy was 14, she saw a neurologist in Missouri who came to believe she was a victim of Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy. However, this doctor never reported her case to authorities. In later interviews, he stated his belief that there wasn’t enough evidence to act.”

Years later, in 2009, “...an anonymous report was made to authorities stating that Dee Dee’s accounts of Gypsy’s ailments had no medical basis. This resulted in two caseworkers visiting their home, but Dee Dee convinced them there was nothing wrong.”

Medical Child Abuse in the Justice System

Tragically, very often cases of MCA do result in the deaths of their victims. As Feldman observed in his 2003 foreword to Sickened:

“A recent study indicates that when a case of MBP is finally recognized, up to twenty-five percent of the sickened child’s siblings have already died—most likely earlier victims of the perpetrator. Only when the same pattern of symptoms appears in the second child of the family, or the third or fourth or fifth, have professionals and legal authorities been forced to realize that motherhood can twist into a strange illness-related type of abuse that, unlike battering or sexual violation, defies ready categorization.”

But the story of Gypsy Rose Blanchard and her mother offered a case where it concluded in the death of the perpetrator. And in the subsequent trial and media frenzy, it was demonstrated just how ill-equipped our systems are to grapple with the realities of Medical Child Abuse.

Dee Dee Blanchard was dead. The medical system had failed to prevent her crimes, and the justice system was now rendered unable to make Dee Dee answer for them. Instead, they were left merely to determine the punishment for her killers. In the case of Nicholas Godejohn, that proved to be a sentence of life in prison. But in the matter of Dee Dee’s daughter and victim, Gypsy Rose, Biography.com has noted that she “agreed to a deal with prosecutors in 2016 because of her prior abuse and received a minimum sentence of 10 years.”

Could there have been another outcome? When it comes to actually prosecuting Medical Child Abuse, Feldman says the justice system can be manipulated to try to minimize MCA in many ways, especially by evoking the Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy verbiage.

“The perpetrator’s attorney in MCA/MBP cases will predictably try to capitalize on misunderstandings among the general public [and among judges and juries],” says Feldman.

Feldman cites several excuses that have been presented to argue against MCA, including claims that these caregivers only did as the doctors told them—“but the doctors based their recommendation on the perpetrator’s false information,” he counters. As for those who question the existence of MCA, as it operates on the premise that an average parent could “outsmart” doctors, Feldman says, “doctors and others are taught to believe what patients and families tell them.”

Perhaps the most jarring reality to grapple with about MCA is the realization of just how ill-equipped both our current medical and justice systems are to even recognize it at all, Feldman says. Regarding “mental health evaluations” that often come into play during legal proceedings, he says, “psychological testing cannot be used to prove or disprove the existence of MBP abuse because there are no mental tests for it, and it cannot be ruled in or out based on interviews–unless the perpetrator confesses.”

The Stories We Tell

The real Baron Munchausen—Hieronymus Karl Friedrich, Freiherr von Münchhausen—was not a malevolent man. He was a veteran of the Russo-Turkish War of 1735–1739, and at the age of 40, he retired to Germany.

There, he became a sort of celebrity amongst the German elite. They relished in listening to his stories, which were in some cases embellished. But Hieronymous didn’t embellish because he wanted glory; he was telling his crowds what they wanted to hear. One person who knew Hieronymous said he told his stories “to ridicule the disposition for the marvellous which he observed in some of his acquaintances.”

In the end, perhaps that’s the one thing we can take away from the term Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy. A reminder of the culpability—not just of the medical professionals or the legal system, but even the fans who consume the true crime content about the mysterious and deeply misunderstood disease, especially the gripping tale of Gypsy Rose Blanchard and her mother.

It’s a reminder that a lie is only effective if people choose to listen to it, to believe it without question. To shrug off doubt, because deep down, we’d rather just be told a story.

You Might Also Like