H.L. Mencken was America's greatest journalist. Should he be canceled? | Matters of Fact

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Journalism, like youth, is a stuff will not endure. It is of the moment. "Tomorrow's fish wrapping."

But there are a few journalists, by dint of great reporting or great style, whose work lingers. It's quoted, anthologized, read long after the subject matter — and context — is ancient history. The classic case is H.L. Mencken. He is still a delight to read. He is also outrageous, offensive, troubling. Politically incorrect, and then some. In the ranks of the canceled, he's a four star general.

Mencken is a test case for our sensitive age. How much do words matter? And what, in the end, counts more: what a person says, or what he does?

And you can quote him

Mencken is remembered inaccurately. His did not say, "No one ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the American public." He did say (Sept 17, 1926 Chicago Daily Tribune) that no one "has ever lost money by underestimating the intelligence of the great masses of the plain people." Which is close.

In the movie "Inherit the Wind" — an otherwise not-bad synopsis of the famous 1925 Scopes "Monkey Trial" — Gene Kelly played him as a smart-alecky cub reporter. Mencken was no such lightweight. He was aggressively learned: his scholarly "The American Language" is a standard reference. He could be funny, caustic, savage. But always, he was "The Sage of Baltimore." Magisterial, even in his put-downs.

Matters of Fact | A column about our lives in the age of media

"Before a man speaks it is always safe to assume he is a fool. After he speaks, it is seldom necessary to assume it."

"Democracy is the art and science of running the circus from the monkey cage."

"Conscience is the inner voice that warns us someone may be looking."

National figure

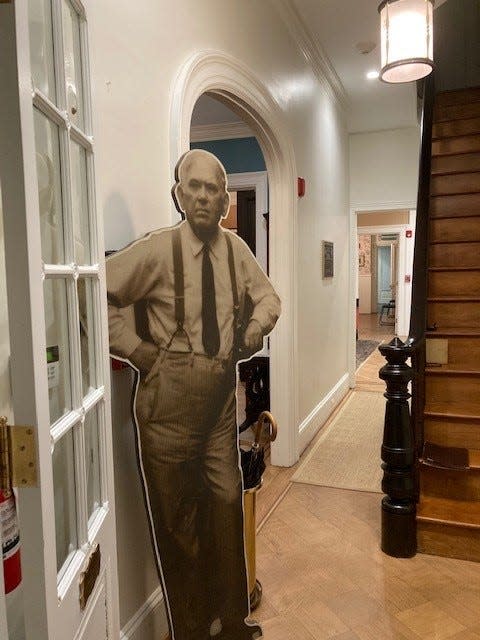

"Mencken is timeless," said Brigitte Fessenden, director and curator of the H.L. Mencken House Museum in Baltimore — the writer's old home (he died in 1956), open on and off to the public since 1983.

"He is admired as an excellent storyteller, literary critic, and observer of the human condition with all its ups and downs," she said. "And never shy of stirring up controversies."

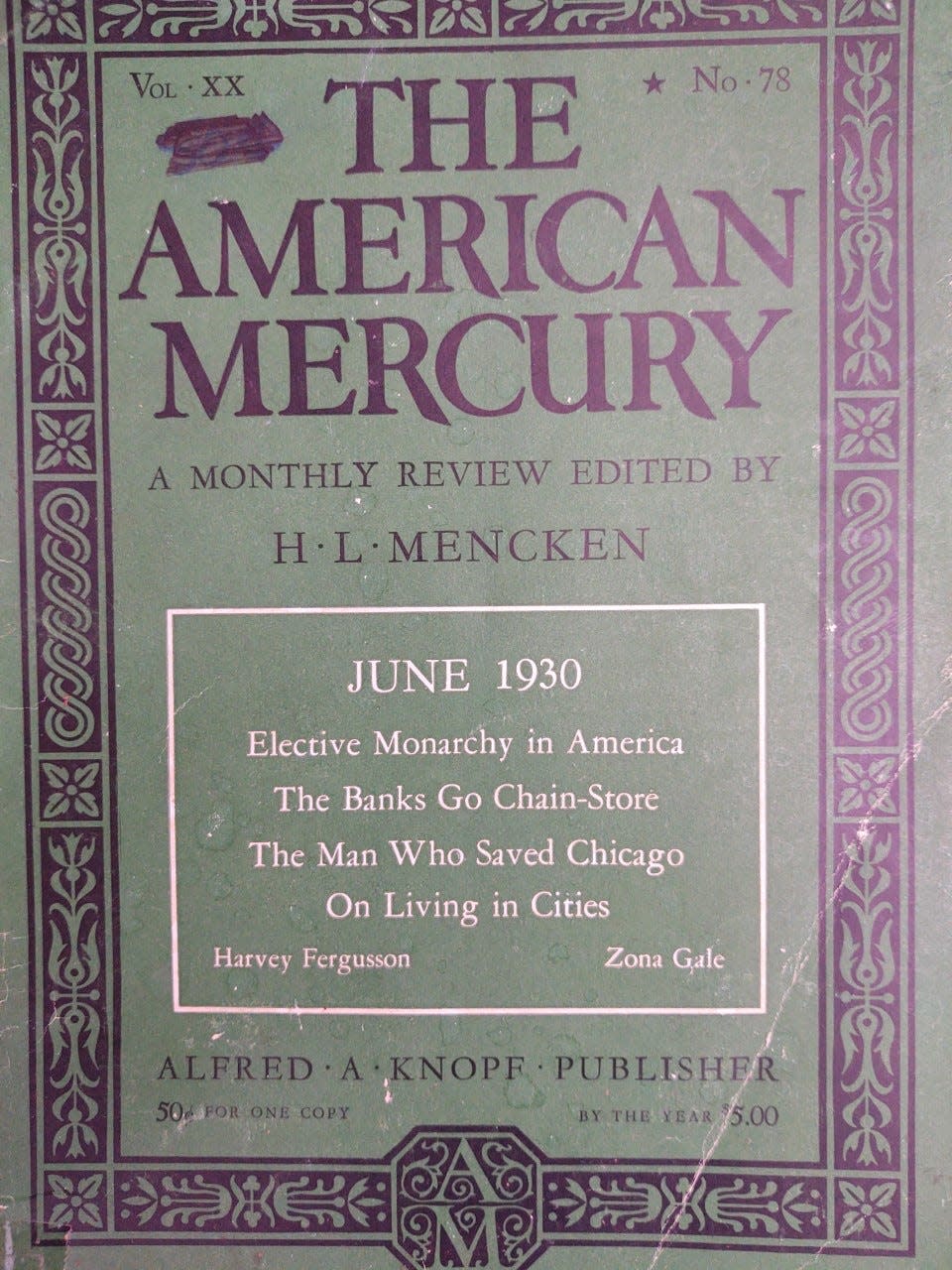

His heyday was the 1920s. He had graduated from Baltimore beat reporter to editor of "The Smart Set" and "American Mercury" magazines — a central figure in America's cultural life, Public Gadfly Number One, the darling of college wisenheimers. His pieces on politics and literature, his snide coverage of the 1925 Scopes trial (the Tennessee teacher who was arrested for teaching evolution), made him a national figure.

He still has a following, as his museum in Baltimore shows. Even more than Bob Woodward or Jimmy Breslin, he is probably the one journalist who made the most people want to become journalists.

"We need voices like Mencken more than ever," Fessenden said. People "who are not afraid uncovering the truth."

But Mencken also said a thing or two. And — trigger warning — some of those things are obnoxious.

'Booboisie'

The Annenbergs of Philadelphia were "low-grade Jews." African Americans were "blackamoors." He called the slaveholding South "a civilization of manifold excellences." Where the money and leisure for those "excellences" came from would likely not have struck him as relevant. He was a social Darwinist, and a skeptic of democracy. "Then why do you live in America?" someone asked him. "Why do men go to zoos?" he responded.

His greatest contempt was for the Southern poor whites — the "boobs" who foisted Prohibition and religiosity on the nation. But he was an equal-opportunity offender. The idea of "punching up" or "punching down" would never have occurred to him. He punched up, down and sideways.

Reactionaries, for this reason, loved him. Some still do. When "The American Mercury" passed out of Mencken's hands, in 1933, it slowly morphed into an ultra-right wing publication — and not entirely by accident. That had always been a subset of its readers. In the novel "Sophie's Choice" the refugee Sophie reads Mencken, at the urging of her boyfriend. He reminds her, she says, of her Nazi father.

Dear diary

The progressives who defended him, meanwhile, on the grounds of "irony" or "context of the time," got a shock when his diaries were published in 1981. His private thoughts were worse.

"The great body of his work remains fraught with error and contains little of lasting value other than, as he might put it, bile, bombast and buncombe," said Ray Jenkins, editorial page editor of The Baltimore Sun, Mencken's old paper, in 1996.

"It is time to bury Mencken, not to praise him," he concluded.

End of story? Not quite. Because there is one other — complicating — fact about Mencken. His Black peers loved him. And he, evidently, returned the compliment.

Ally

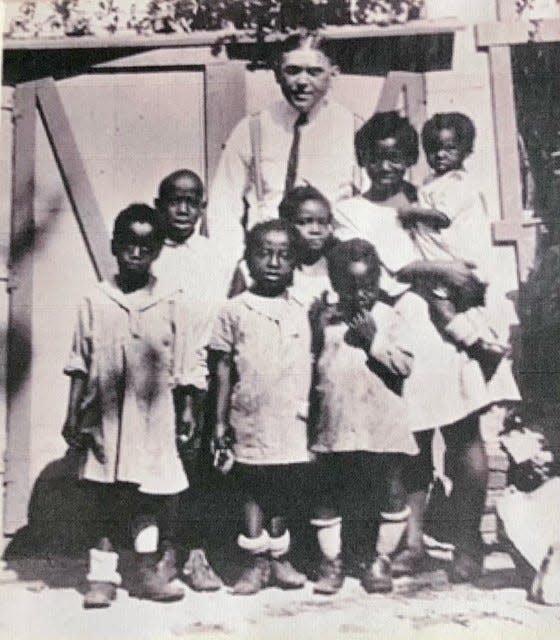

W.E.B. Du Bois, James Weldon Johnson, and other key Black intellectuals were in regular correspondence with him. He published their articles in his magazines — few other white publications would have done so — and he wrote articles for theirs. "The white man, it seems to me, is extremely ridiculous," Mencken wrote in The Crisis, the NAACP's magazine. "He looks ridiculous even to me, a white man myself. To a Negro he must be an hilarious spectacle."

In his more serious moods, Mencken editorialized against lynching and, in 1948, for the integration of Baltimore's tennis courts. Germanophile though he was, he argued that America should take in Jewish refugees from Hitler. He championed women: they were, to his thinking, the smarter, less delusional sex.

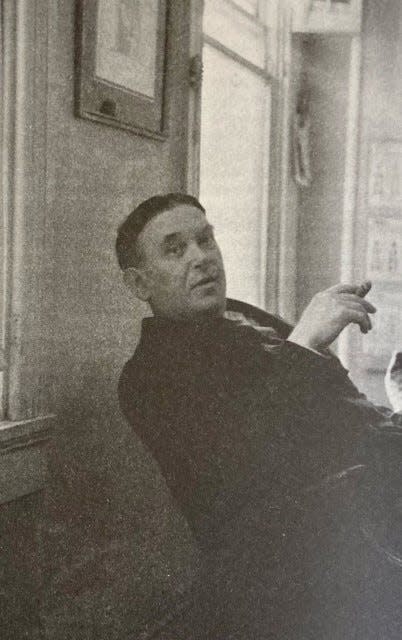

For Black readers, seeing Mencken take on the white establishment was empowering. In his 1945 memoir "Black Boy," novelist Richard Wright describes the trouble he went through to get a Mencken book from the Memphis library (he had to pretend he was illiterate, and getting it for his white boss), and the electric effect it had on him.

"He was using words as a weapon, using them as one would use a club," Wright recalled. "Could words be weapons? Well yes, for here they were. Then maybe, perhaps, I could use them as a weapon?"

Mencken mentored Black writers as much as anyone in his time. That's telling. Not helping people — on the grounds that certain types are "naturally" inferior and therefore may be neglected with a clear conscience — is the classic mark of the racist. That's the opposite of Mencken.

'Sheer buncombe'

No doubt he would have had choice things to say now, both about the word-policing of the left and the book-banning of the right. "I believe in free speech to the last limits of the tolerable," he once said.

So how tolerable, in the end, is Mencken?

We're in an era where we take words seriously. Maybe too seriously. An offhand stupid remark, made by a drunken 17-year-old online, is enough to ruin a career 20 years later.

Mencken made plenty of those remarks. Enough to ruin 20 careers. Unforgivable? Probably. But the life he lived, and the people he helped, tell a different story.

Perhaps the key to the Mencken conundrum is that, to the end, he remained a journalist. From the French "jour." Journalism is of the day. Tomorrow's fish are always waiting.

He wrote mainly to amuse — he is still funny today — and produced a lot of words over 50 years. He may have taken most of them lightly. Too lightly, for modern tastes. Analyzing the role of the critic, in 1922, Mencken wrote: "It must occur to him not infrequently, in the silent watches of the night, the much of what he writes is sheer buncombe."

And there you have it. Mencken, giving the game away.

The irony is that, in the end, Mencken's words do matter. They matter to the people who are still defending and denouncing him. And they mattered, 80 years ago, to at least one Black teenager —who went on to write "Uncle Tom's Children" and "Native Son."

Jim Beckerman is a media columnist for the USA TODAY Network's Northeast Group. For unlimited access to his insightful reports about how you spend your leisure time, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: beckerman@northjersey.com

Twitter: @jimbeckerman1

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: The problem with H.L. Mencken, America's greatest journalist