Haiti-born Didier William's dazzling, gazing paintings are literally an eyeful

It is a source of the divine and of evil. It is vulnerable and powerful. It is a filter of light as well as its ultimate source. The eye, wrote 20th century Spanish poet Juan Eduardo Cirlot (citing the ancient Greeks), "would not be able to see the sun if, in a manner, it were not itself a sun." The eye illuminates; to see is "a spiritual act and symbolizes understanding."

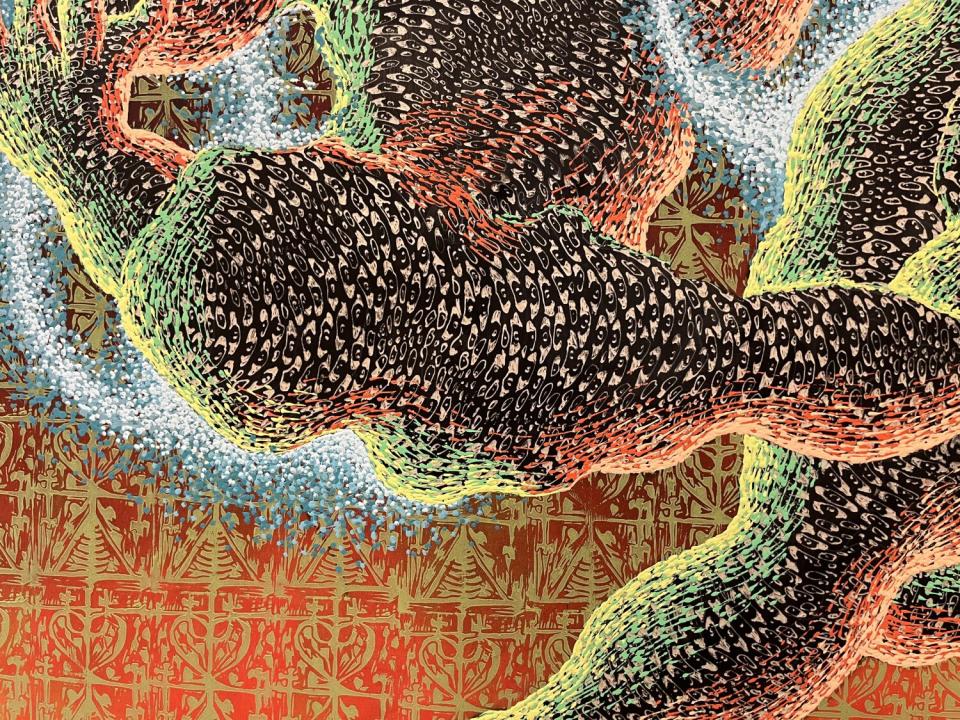

The eye — with its many meanings — makes repeated appearances in the fantastical (and fantastic) paintings of Didier William, currently the subject of a one-man show, "Didier William: Things Like This Don't Happen Here," at James Fuentes gallery in Hollywood. Amid otherworldly landscapes that seem to buzz with sentience and pulse with electricity, William places mysterious, faceless figures whose skins consist of hundreds, if not thousands, of eyes.

The eyes are a way for Black bodies to reflect the intense scrutiny so often thrust upon them. "It's a way for the figures in my paintings to return the curious gaze," William told me in a telephone interview in 2018. "Not just with their eyes, but with every square inch of their skin."

The eyes have other purposes too. "They are like apotropaic amulets warding off the evil eye: an army of ever-watchful, unblinking, cyclopean eyes," wrote critic Zoé Samudzi in a short monograph of William's work published in 2021. "They are the materialization of an autonomous and collectivized claiming of the right to look."

There is a lot going on in the work of William, a Haiti-born, Miami-raised artist now based in Philadelphia. His work first grabbed my attention in the group show "Relational Undercurrents: Contemporary Art of the Caribbean Archipelago" in 2018 at the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach. That exhibit featured his 2015 canvas "They play too much, till we stop playin," in which one of his eye-covered figures wrestles shadowy appendages on a wooden stage. Was it a body wrestling unseen forces? Or struggling against itself? It's hard to say, but the tussle was engrossing.

Since then, I have stumbled upon his work in group settings on a handful of occasions, most recently in "Forecast Form: Art in the Caribbean Diaspora, 1990s-Today" which was presented at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago earlier this year (and will travel to the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston in the fall).

Each time I've run into William's paintings, I've been floored — not only by the ways he uses imagery but also by the careful crafting of his pieces. The exhibition at James Fuentes, which inaugurated the New York-based gallerist's L.A. space early last month and is now in its final days, provides an opportunity to soak up a number of his works in a single setting on the West Coast.

The solo show gathers 14 new paintings that delve into the otherworldly as well as the biographical.

A large vertical canvas titled "Plonje (Dive)," made this year, shows three faceless figures plunging into a watery deep. It evokes the ways in which the seas around Haiti have served as a graveyard to Africans and their descendants, beginning with the Middle Passage and continuing through the perilous journeys Haitians still make to Florida today. But these supernatural eye-covered bodies slip through a body of water that also has eyes. The scene evokes death, but there is life as well. The mystical nature of the figures reminds me of Drexciya, the mythical world devised by the Detroit musical group of the same name — an underwater universe peopled by the superhuman descendants of enslaved women whose bodies were thrown from slave ships.

Another canvas, "I Wanted Her to Kill Him, I Know Why She Didn't," also from 2023, is more personal. It was inspired by the artist's mother, a restaurant worker who contended with an abusive boss. It shows a figure blasting another with rays of light inside an abstracted room. The walls are covered in a repeating pattern of vèvè symbols, the ritual designs employed in Haitian Vodou. In this case, a heart pattern evoking Erzulie Dantor, a protective maternal spirit.

From a distance, the paintings swirl and seethe with motion and bright splashes of color. Particularly memorable is a large horizontal piece that was inspired by an episode from William's childhood, when he was hit by a car after chasing his dog into a busy street. "My Father's Nightmares: 40mph Hit" shows a stand-in for the artist catapulted into the air by the force of the impact; in the distance, his father waves his arms helplessly. Binding the scene together is a thread of blue-white light that connects the two figures but that also seems to track William's motions through time and space. Is it possible for a car accident to be hauntingly beautiful? This one is.

Most remarkable, however, is the detail you'll find when you move in close. William produces his paintings on wood panel, and he frequently carves the eye patterns into the wood itself, albeit very lightly. This gives his eyes texture, but not in a way that greatly interrupts the surface of the picture. It deepens a sense of illusion: His figures are of the painting but not entirely of the painting — inhabiting a nether material state.

William likes to say that he "antagonizes paintings with other mediums." I'd venture to say that "conjuring" might be a better word, since these are works that feel as if they've been touched by a little bit of magic.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.