New Hampshire will run cannabis franchise stores if bill passes: How it would work

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If New Hampshire lawmakers pass the cannabis legalization bill preferred by Gov. Chris Sununu in 2024, the business model might look a little like McDonald’s.

One large entity – the New Hampshire Liquor Commission – would oversee all the products, the marketing, and the layout of retail stores. But individual stores would be run by individual owners, who would hire their own employees and be responsible for their own profitability. And the stores would be able to sell only products tested and approved by state officials.

That’s the vision from Liquor Commission Chairman Joseph Mollica, who presented a blueprint this week for how lawmakers might move forward.

“The model that we are looking to put in place, that we feel would be feasible, is that the Liquor Commission would be the franchisor and the franchisee would be the retailer,” Mollica told a study commission Monday.

Under the proposed plan, the commission would allow up to 65 cannabis retail establishments across the state. That represents the number of liquor outlets currently operated or licensed by the state. The commission would never let the number of cannabis outlets exceed the number of liquor outlets statewide, and it would apply similar limits to individual cities and towns, Mollica said.

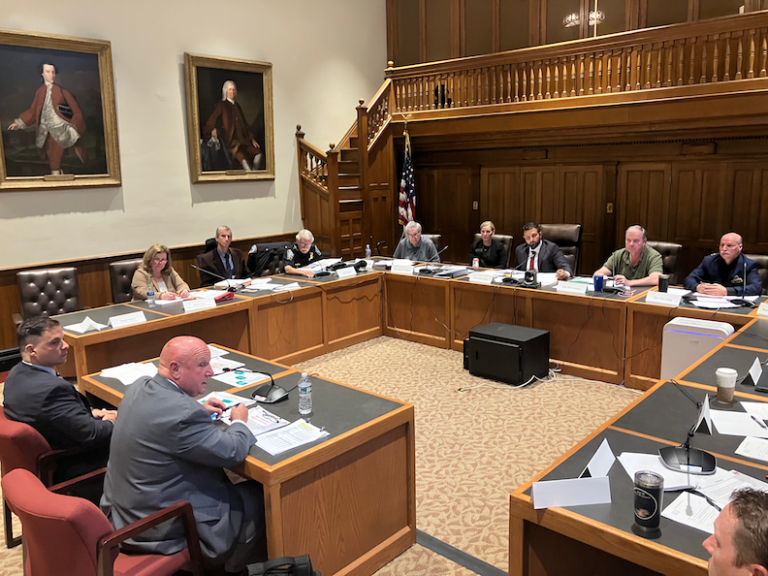

Mollica gave his presentation to members of the Commission to Study With the Purpose of Proposing Legislation State-Controlled Sales of Cannabis and Cannabis Products, a panel of House and Senate lawmakers and other stakeholders that will meet throughout the fall to try to recommend statutory language ahead of the 2024 session.

In May, Sununu reversed a longstanding position against legalizing cannabis in New Hampshire, issuing a statement saying he would approve legislation to do so as long as it met specific requirements. All legal sales and marketing would need to be controlled by the state, the state would need to prevent concentrated “marijuana miles,” and the state would need to prioritize harm reduction over profits, Sununu announced.

“Similar to our liquor sales, this path helps to keep substances away from kids by ensuring the State of New Hampshire retains control of marketing, sales, and distribution – eliminating any need for additional taxes,” Sununu said in a statement.

No state that has legalized cannabis has attempted a controlled-sale retail model; those that have legalized retail have allowed private businesses and organizations to sell it. After Sununu’s announcement, state lawmakers quickly passed legislation forming the study commission to determine how to make that model a reality.

The Liquor Commission’s suggestions this week are not binding; lawmakers must propose the bill creating the legalization model, pass it through both chambers in 2024, and then approve administrative rules after passage that would sort out specific details. But Mollica’s presentation provided the clearest glimpse yet of what the model could look like.

During his presentation, Mollica said the state would seek to oversee and facilitate a supply chain between growers, manufacturers, and retail franchisees.

Due to federal prohibitions against selling cannabis across state lines, all cannabis sold in New Hampshire would need to first be grown here. The state would not control that growth, but would instead award licenses to farmers and businesses to meet that demand, Mollica said.

The state would also create a licensing process for manufacturers of cannabis products, such as edible foods like gummies, brownies, and chocolate, as well as capsules, cartridges, oils, and concentrates.

And the state would issue licenses to retail operations, with the agreement that 15 percent of gross monthly sales would be delivered back to the Liquor Commission. Mollica said the initial cost of licenses might be around $25,000 per outlet, with subsequent licensing fees tapering down every year until they reach a steady annual payment of a few thousand dollars. As proposed, owners of the licenses would be able to sell them to others, provided the new owners pass the approval process by the commission.

The commission would set the wholesale prices that would be used to pay growers and manufacturers. But individual franchises might price their products differently, depending on factors such as the local cost of living and their proximity to state borders and highways. The growers, manufacturers, and retailers would be responsible for transporting and distributing cannabis products.

While the commission operates 65 liquor stores, it would not sell cannabis products in those stores. The cannabis stores would be separate locations with their own logos, Mollica said, and the Liquor Commission would likely prevent them from being established in the same shopping plaza or building.

The franchise model provides a potential legal shield for the state: Should the federal government begin to take action against cannabis retailers in states that have legalized, the state would not be obligated to defend the franchise employees in court, Mollica said.

Cities and towns would be required to opt in to hosting cannabis retail stores, likely through town warrant articles or city ballot initiatives. Those municipalities that did opt in would share in 1 percent of the state’s total cannabis revenue, Mollica proposed.

The state currently allows “alternative treatment centers” to dispense therapeutic cannabis for people with qualifying conditions identified by physicians. Under the proposed model, those treatment centers could also apply for licenses to host franchises to sell recreational cannabis, Mollica said.

In order to oversee the new line of products, the Liquor Commission would need to hire 10 new employees in its enforcement division, 10 in administrative roles, and nine in marketing and advertising roles, Mollica said.

The state would contract with a third-party vendor to carry out testing of its cannabis products – as well as inspections of manufacturing processes, Mollica said. But the commission would deploy its own full-time cannabis enforcement officers to investigate potential violations.

Under the commission’s proposal, all products sold would be required to include a warning label about the effects of cannabis; nutritional facts; a list of ingredients and allergens; and a clear picture logo that would indicate that the product contained cannabis or THC. The packaging would need to be opaque and childproof, and the commission would not allow packaging or labeling that mimics or resembles commercial products, such as candy. The outside testing vendor would verify the THC levels of each product before it was sold.

Any marketing directed at children or athletes would not be allowed, Mollica said. And unlike with alcohol sales, free samples and giveaways would be prohibited.

Members of the commission appeared supportive of many of the recommendations. But some had lingering concerns.

Rep. Tim Cahill, a Raymond Republican, said he worried the packaging around edible products might still be enticing to children. Rep. John Hunt, a Rindge Republican and chairman of the House Commerce Committee, said he would push to specifically ban that type of packaging.

Bedford Chief of Police John Bryfonski, president of the New Hampshire Association of Chiefs of Police, said he was also concerned about accidental ingestions of cannabis products by children. Sen. Becky Whitley, a Hopkinton Democrat, proposed adding a requirement that the cannabis stores sell lockboxes that patrons could choose to buy to keep the products away from their kids.

And Sen. Daryl Abbas, a Salem Republican and the chairman of the commission, added that the lawmakers should lay out detailed rules for how a retailer might lose their license for “egregious” violations.

“That’s up to the legislation and the rule – we’re neutral on how we feel,” Mollica said. “Whatever you feel is best. … As far as where it goes, if it’s a one-strike, it’s a one-strike. If it’s a two-strike, it’s however it needs to be.”

The commission will continue meeting until Dec. 1, when it is required to produce a report with recommendations.

This story was originally published by New Hampshire Bulletin

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: NH may run cannabis franchise stores: Here's how it would work