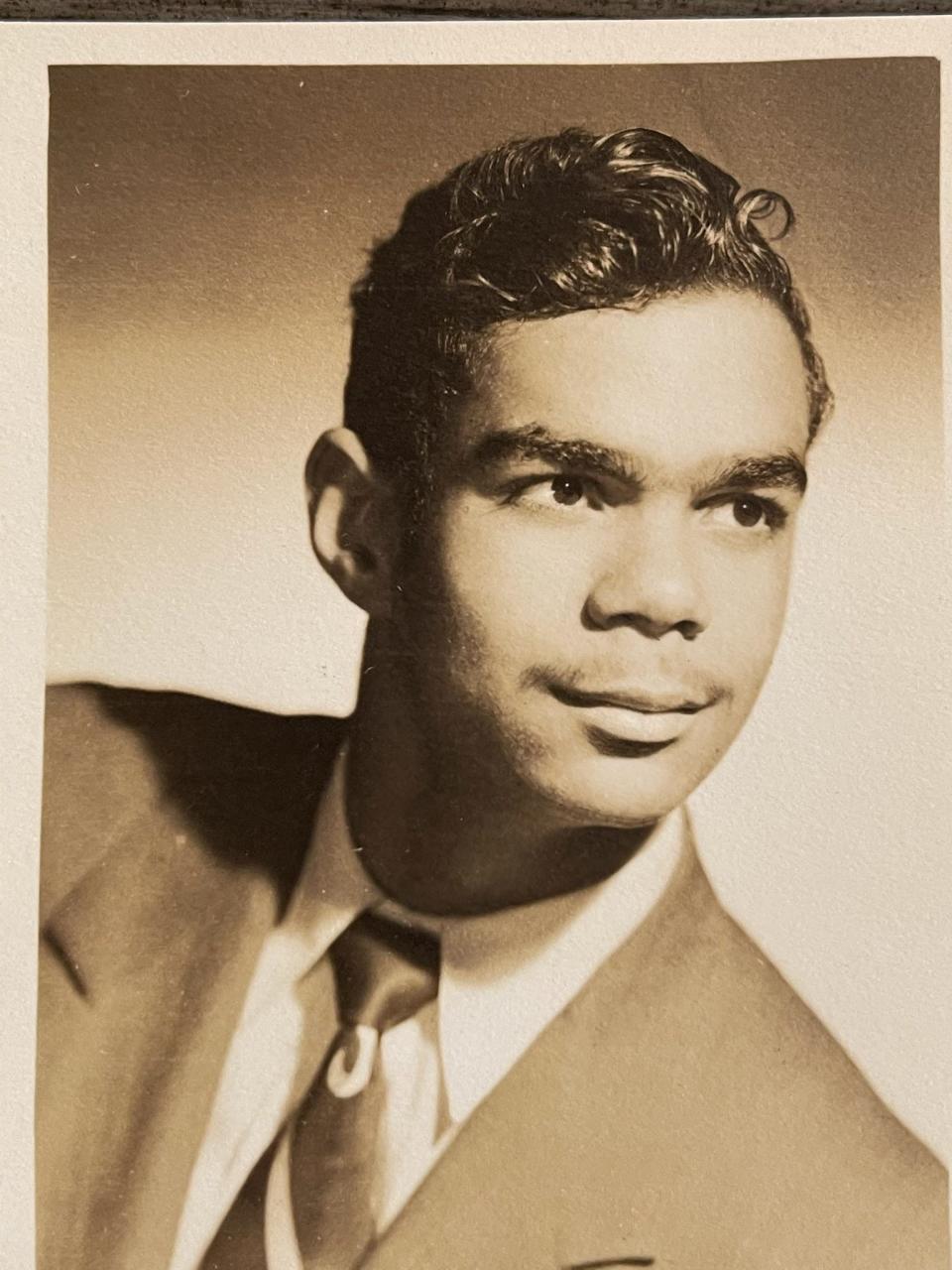

Hank Foster was Butler basketball's first Black player. But he was so much more than that.

The backboard, at least what’s left of it, sits at the end of St. Nicholas Boulevard. In the 1970s, when Marcia Foster was growing up in the east end of Plainfield, N.J., it was affixed to a light post. A few nails are all that remain now.

Under the light is where Foster learned basketball with her father, Hank. St. Nicholas juts into an L shape at the end of the road, so the only traffic came from people who lived there. The interruptions to their shooting sessions and 1-on-1 games were minimal.

Much of Hank Foster’s significance to the world of Indiana sports is well documented. A track and field star who could clear six feet on the high jump while taking off from sand, it was track that brought him to Butler in 1953. There were no dorms available for him at the time, so a friend arranged for him to live with a Black family.

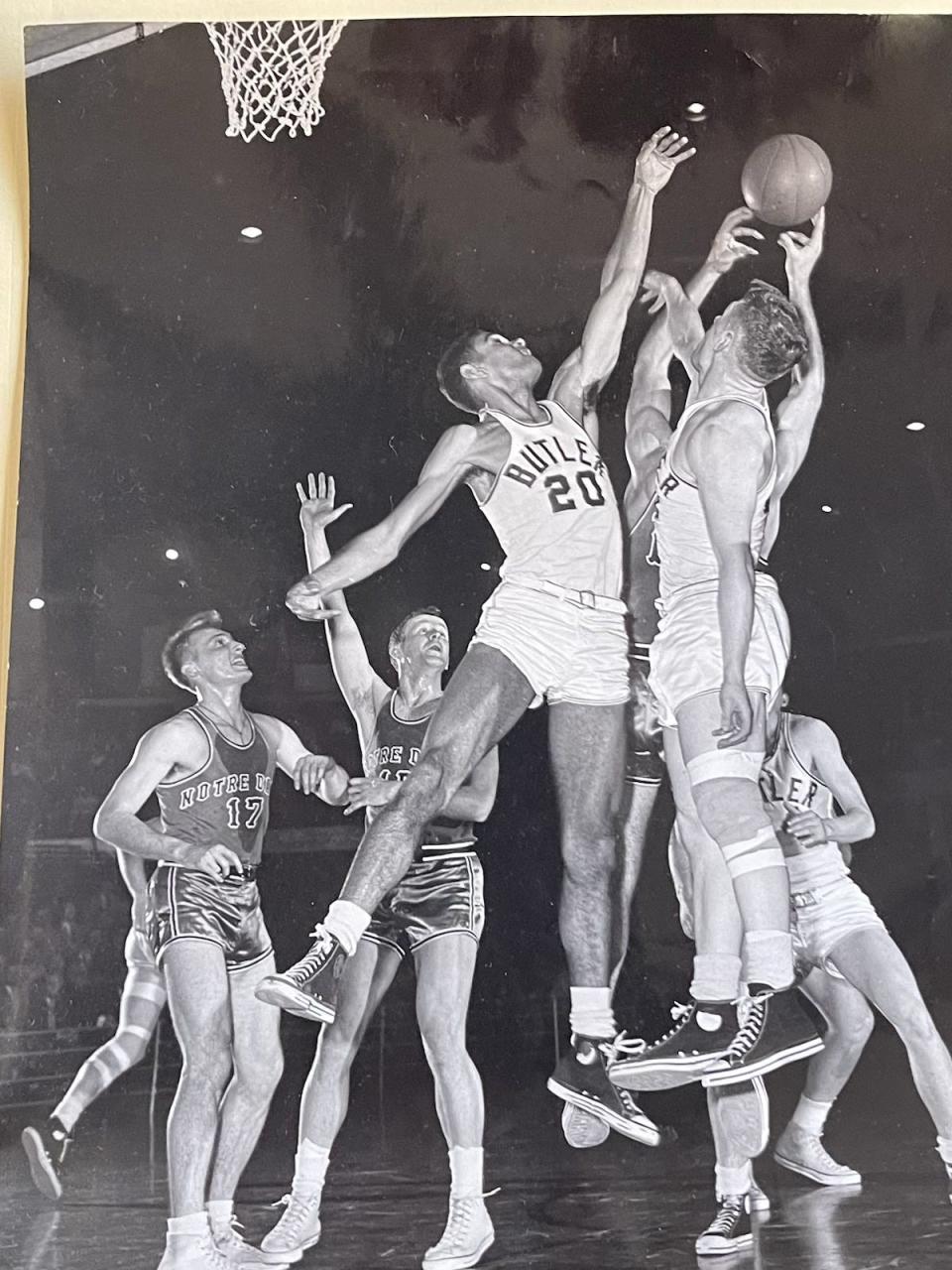

He ended up playing basketball when Butler coach Tony Hinkle, undeterred by the fact that Foster had never played before, was impressed enough with his athleticism and potential to recruit him to the team. Foster became the first Black player in program history.

More:Hank Foster came to Butler for track — and became school's first Black player

By his junior season, the 6-4 Foster became the Bulldogs’ starting center. He averaged 5.9 points and 8.3 rebounds in 1955-56 and 4.7 points and 6.6 rebounds in 1956-57, according to Sports Reference. He played 48 games over three seasons with the Bulldogs and won the Andy Williams Award as a senior, an honor based on character and attitude.

But Foster’s story didn’t end when he left Indianapolis. In fact, to many who knew him after college, his pioneering basketball career was an afterthought. Back in Central New Jersey, beginning in the 1960s shortly after his return and lasting nearly until his death in 2020, he forged a new path for himself, for his family, for Plainfield.

What Foster lacked in skill on the court he made up with physicality and grittiness. He ran the floor, crashed the glass and played hard defense. On St. Nicholas Blvd., Foster wasn’t afraid to bring the same intensity to games with his daughter, slapping at her hands to knock the ball away, talking the occasional trash.

The point was to mold Marcia, who later played at Seton Hall and coached at Fullerton College in California, into the kind of player her dad was, someone tough and physical and unafraid. Her high school coach compared her to Charles Barkley because of the way she moved opponents out of her way.

Still, there was more to those 1-on-1 games than basketball.

“Those little lessons I remember taught me how to be tough as a young woman, too,” Marcia said. “How to be tough. How to stand my ground. How to speak my mind. Smacking the ball out of my hands, being aggressive with me, it was to get me to stop having expectations of someone taking pity on me on the court. That’s not how I was gonna be successful. In retrospect, when I think about that, that’s what that was about.”

The lessons were always about more than what was on the surface, even if Foster wouldn’t say it. The 1-on-1 games at the end of the street were to teach Marcia toughness. When the family — Foster, his wife Sharon, Marcia and her two brothers — drove across the country to California to see relatives, Foster wanted his kids to see more of the country and understand there was a world beyond Plainfield, N.J.

'Everybody in Plainfield knew Hank and respected him.'

The racial divide in 1960s Plainfield was similar to that of many other cities. Housing was mostly separated, so was Plainfield High School. Industry and jobs had been in decline in the predominantly Black west end since the end of World War II, according to the Courier-News, the local paper.

As unrest rumbled across the country throughout the summer of 1967, a July 14 incident outside the White Star Diner in Plainfield — reports of what incited it have been conflicting over the past five decades — kicked off three days of rioting. Automatic weapons were stolen from a nearby arms factory around the same time. It all eventually drew a “contingent of 100 National Guardsman,” wrote Charles L. Dustow of the Courier-News at the time.

Foster was familiar with the philosophies of both Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. His own aligned with those of King. He and his friend Milt Campbell, a well-respected former Olympic decathlon gold medalist from Plainfield (and Indiana University graduate), knocked on doors early in the unrest.

Details of specific conversations 56 years ago are hazy, but the consensus among those who spoke to IndyStar is that the two tried to deescalate the situation. They encouraged anyone with stolen guns to get rid of them, hoping to prevent the National Guard from entering Plainfield.

“He was very influential in working with the authorities and trying to bring calm to the city because everybody in Plainfield knew Hank and respected him,” said Canon Lyons, Foster’s friend and minister of his church for 41 years. “Every single person.”

The civil rights work, the difficulty he faced at Butler, much of it was lost to history as Foster raised a family in the ‘70s. Marcia didn’t know the story of Hinkle recruiting Foster to play basketball until she was in college herself. He didn’t tell her the story of going door-to-door in 1967 until a few years before he died. Foster’s brother Donald found out he was the first Black player at Butler long after the fact.

“I tried to pick up the pieces later on, but I guess he was kind of tired of it all,” Donald said. “He would answer the questions if I asked them, but I guess I was kind of boring because I didn’t know to ask the deep questions. He would answer them, but it was almost like, ‘C’mon, man. That was years ago. Everybody’s supposed to know that.’”

Later in life, Foster’s stories to his family came out in bits and pieces, like the time he and Marcia were at a five-and-dime store and he pointed out a police officer who had once beaten him with a billy club. Foster didn’t elaborate. He didn’t go into detail or tell Marcia to avoid the officer. He just wanted his daughter to be aware.

'Like he was the mayor.'

Foster spent his later years as something of an ambassador within Plainfield. He was a vice principal and a principal at the junior high and high school and was the senior warden in his church for 20 years.

“He had everybody’s ear and he certainly had the respect of the community,” Donald Foster said. “Occasionally we would go to a parade or something in Plainfield and people would call out, ‘Hey, Mr. Foster! I see you got your kid brother with you now.’ Everybody was like, “Mr. Foster, Mr. Foster.’ It was almost like he was the mayor.”

His personality remained consistent throughout all of it. He rarely spoke of his athletic accomplishments. His main priority remained helping people. He took it upon himself to devise a system of conflict resolution at St. Mark’s Church, sitting down with people and acting as a mediator.

When he felt that meetings within the church were taking too long, he began sitting down with members of the leadership individually, allowing them to pitch him their rough ideas and streamlining the process during larger gatherings.

There was one rule: don’t disturb him while he was eating lunch. At Plainfield High School, it was the one hour of the day he wasn’t to be bothered with the community’s problems.

He continued to play basketball in an amateur league. Even if he didn’t like to talk about his days at Butler, he had the same style of play: physical, scrappy, tough. Marcia frequently watched and described him as an enforcer.

It was fitting for a man who was the same person in every stage of his 84-year life. He played basketball no differently than he had when he was younger. He interacted with others and deflected attention from himself in the same way he always had.

His focus remained on others, the way he preferred.

“That’s who he was,” Marcia said. “If people don’t reach back and don’t give back, the communities don’t change. People don’t have opportunities to change. I know this because I’m his daughter and I’m the same. He passed on those lessons. So caring for the community, if Black people didn’t care for the Black community during the '60s and '70s and '80s and still, then how would things change if people weren’t there trying to lift up a community? And my dad was acutely aware of his responsibility to do that.”

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Butler's first Black player Hank Foster's life more than basketball