What would happen if we pursued our unique interests and hobbies? Ask Jay Villemarette

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

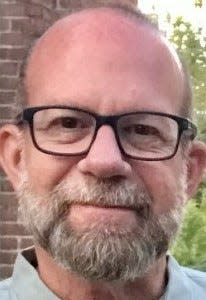

Jay Villemarette was 7 when he made a discovery that would open his world and determine the course of his life.

It happened 50 years ago this summer. Villemarette was walking in the woods behind his house with his dad and brother, when the boys found something rolled up in a blanket. They unfurled it, and there it was: a dog skeleton.

Looking back, it’s not what his dad said that altered his life. It’s what he didn’t say.

“It would have been easy,” Villemarette says, “for Dad to say, ‘Put down that dirty bone, don’t touch it.’ But he didn’t. He saw my interest, and he let me follow it.”

That moment opened the floodgates to Villemarette’s curiosity. He kept the dog’s skull. He found it fascinating. A few years later, he found a cat’s skull on an ant hill. He took it home and studied the similarities and differences in the two specimens — the eyes, the teeth, the shape. His search for bones continued. He found a skunk, then a beaver. Each discovery sent him to the library near their house at SW 89 and S Pennsylvania. It was a gold mine of information about his hobby.

More: Guest: Imagination, recess don't have to end with childhood. It's good to feel like a kid again.

When he was a teenager, Villemarette’s dad would get home from work at 4:30 p.m., and they would hop in the family car and scour the county roads for roadkill. It was bountiful: raccoons, opossums, armadillos, snakes. Young Villemarette decapitated each of them, cleaned and scrubbed the skulls, and added to his collection.

Curiosity can lead one down a number of winding roads. In 2010, Jay Villemarette’s curiosity ultimately led him to create the Museum of Osteology. Located along an unassuming stretch on the southeast side, it’s one of Oklahoma City’s most curious — there’s that word again — and surprising treasures.

The collection includes about 7,500 specimens. Ten percent of them are on display, and tastefully so. Practically every week, Villemarette hears from adults who work in animal care, archaeology or science, who credit the museum for sparking their curiosity as kids.

Villemarette’s story serves as a reminder of the importance of pursuing what makes you happy — what feeds your soul. Even as an adult. Especially as an adult. You don’t have to make a career of it. But giving yourself permission, time and energy to lunge headfirst into your interests will scratch an itch than cannot otherwise be reached.

Consider it a form of self-care. One of my business partners makes the analogy of the flight attendants’ safety instructions before takeoff. What are we to do when the oxygen mask drops? We put ours on first. We have to be well first, so that we can help others be well.

Pursuing our interests can give us the break and headspace we need to be fully functional in our other roles. Even if it’s a weird hobby. Even if it’s uniquely you. Even if you find yourself on a county road, searching for who-knows-what. You never know where that road may lead.

Russ Florence lives and works in Oklahoma City. His column appears monthly in Viewpoints.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Museum of Osteology a result of child's curiosity, pursuit of interest