What Happened to Medicare For All?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Does anyone remember “Medicare for All”?

The issue seems to have disappeared from mainstream political discourse. Those of us who still care about it can feel like characters in George Orwell’s 1984 who could swear that they remember a time when Oceania was allied with Eastasia in a war with Eurasia and not the other way around. Wasn’t everyone just talking about Medicare for All?

Progressives have dreamed of instituting some kind of “single-payer” or “Canadian-style” health-care system in the United States for many decades, but Sen. Bernie Sanders popularized the proposal under the “Medicare for All” label during his race against former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination.

Secretary Clinton dismissed it as an unserious socialist fantasy, but the idea continued to pick up steam over the course of the next few years.

Neither Party Cares About the Working Class

As hard as it may be to remember, arguments about Medicare for All dominated the race for the 2020 Democratic nomination. At the beginning of the cycle, several serious candidates said they supported Medicare for All.

Sens. Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and (for a brief moment) Kamala Harris all said they wanted to completely nationalize the health insurance industry. The idea was in the air. Sanders was even able to win over the crowd at a Fox News town hall, convincing them of the benefit of giving up their private insurance plans for a universal public plan.

The most moderate candidates with a real chance at the nomination, Joe Biden and former South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, split the difference by saying they wanted “a public option” (Biden) or “Medicare for All Who Want It” (Buttigieg).

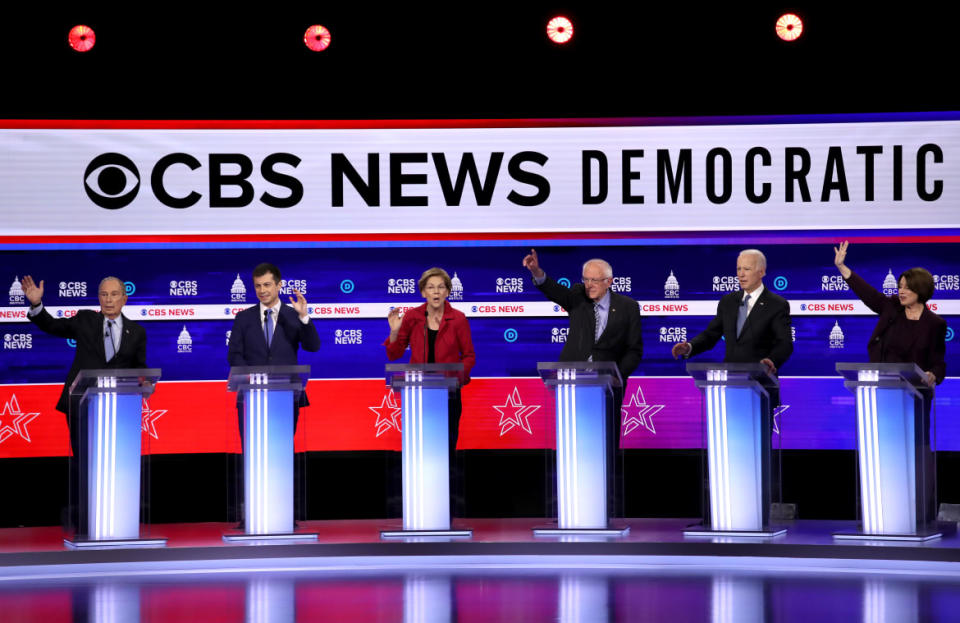

Democratic candidates debate in 2020.

Warren eventually decided that she wanted to split the difference, with a confusing two-phase plan for achieving the ultimate goal of a single-payer system.

Sens. Cory Booker and Kirsten Gillibrand, Reps. Tulsi Gabbard and Tim Ryan, former HUD Secretary Julian Castro, and Andrew Yang all sided with Biden and Buttigieg in wanting to preserve some role for private insurers—but they all at least started out by branding their proposals simply as Medicare for All. (Harris also eventually recalibrated, and joined the centrists.)

In 2020, meeting Bernie-ism halfway was the moderate position.

Various combinations of these candidates were brought together for what felt at the time like 100,000 hours of televised debates. And, over and over again, a significant portion of the evening was spent sparring on issues like how long the transition from the status quo to some sort of system of state-backed universal coverage should take, and whether private health insurance companies should exist at all.

Everyone insisted that of course there should be a legal guarantee that every man, woman, and child in the United States would be covered by some health insurance plan—and of course they didn’t think anyone anywhere should have to deal with Aetna or Blue Cross Blue Shield if they would prefer to be insured by the federal government.

Joe Biden unambiguously stated in a section of his campaign website that’s never been revised that “[w]hether you’re covered by your employer, buying insurance on your own, or going without coverage altogether, Biden will give you the choice to purchase a public health insurance option like Medicare.”

Before the Never Bernie crowd settled on Biden, their great centrist hope was Pete Buttigieg—and under his plan, people “going without coverage altogether” would be automatically enrolled in the public plan without having to do anything to purchase it.

In state after state, no matter who won any given primary or caucus, Democratic voters told pollsters that they wanted to simply replace the private insurance system with a single government plan.

I argued at the time that the differences between “Medicare for All” and “Medicare for All Who Want It” were more important than they might look to a casual observer, and I still believe that—but the common ground of all of the Democratic plans was supposed to be that no one should be involuntarily denied government-provided health insurance. So, now that one of these candidates is the President of the United States, another is vice president, a third is a Cabinet secretary, and several others are back in the Senate… what the hell happened?

Last year, Politifact generously rated Biden’s campaign promise of a public health insurance option as “stalled” rather than broken. But even that’s a stretch. As Politifact itself notes, there was never any attempt at putting a public option in a reconciliation bill. (It’s tough to make the argument that putting tens of millions of Americans—and that’s just a conservative estimate—on a government-provided insurance plan wouldn’t have the “non-incidental” budgetary consequences required for bypassing the Senate filibuster.)

While no major figure has taken up the idea, there’s also a creative legal argument that Joe Biden could unilaterally give every American who’s in danger of exposure to COVID-19—which is to say, every American—access to Medicare through a broad interpretation of Section 1881A of the Social Security Act.

Perhaps none of these maneuvers would work. But questions about parliamentary tactics are the least of it. What can’t be blamed on centrist Democratic Sens. Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, the Senate rules, or how the courts might interpret Section 1881A is the simple fact that Biden and (almost) all of the rest of the 2020 candidates have just stopped talking about it.

Progressives Who Want Joe Rogan Off Spotify Should Be Careful What They Wish For

At a time when Democrats are facing the very real prospect of a catastrophe in the midterms, it’s far from clear that this choice makes sense even in cynical political terms. Medicare for All has long polled well, and it’s hard to see how loudly and proudly fighting to give everyone health care could make the Democrats’ electoral situation worse.

More importantly, insuring the 31 million people who don’t have health insurance at all, while providing public insurance to the far larger number who have to deal with frequently inadequate coverage from profit-driven private insurance companies, is an urgent moral imperative. So is freeing all the people who have good health insurance, provided by their employer or their spouse’s employer—and who end up being trapped in bad jobs or even bad marriages as a result.

The United States has a lower life expectancy, higher infant mortality, and a higher rate of “mortality amenable to health care”—that’s statistics-speak for people dying because they didn’t see a doctor in time—than culturally and economically comparable nations, such as Canada and the U.K. Life expectancy in the U.S. varies sharply from zip code to zip code.

Democrats claimed to care about these grim facts in 2020. How seriously can we take that, though, if they let the subject drop until the next year when they have to run against each other for their party's nomination?

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.