‘What is happening in Florida will not stay in Florida.’ Are NC colleges next?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Florida has dominated much of the national conversation over higher education in recent years, with lawmakers targeting diversity efforts at state colleges and universities, altering faculty tenure policies and overhauling the governing board of a small, public liberal arts college with conservative trustees.

Florida’s changes have been widely publicized — and often criticized — but they are not unique to the Sunshine State. North Carolina leaders are making several moves in the same direction.

“We are seeing significant changes in the ways in which higher education, and particularly public higher education, is being regulated,” Sigal Ben-Porath, a University of Pennsylvania professor who studies education in the context of democracy, told The News & Observer, adding that those changes are “being driven by mostly Republican goals and visions for higher education.”

A May preliminary report from the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) warned that Florida’s actions are part of “a politically and ideologically driven assault unparalleled in U.S. history,” and cited Ohio, Texas and Tennessee as key states where leaders and legislators are enacting higher education policies similar to those in Florida. The national faculty group released its final report on the topic Wednesday.

“What is happening in Florida will not stay in Florida,” the preliminary report stated near the end of its 18 pages.

Though North Carolina was not listed in the May AAUP report, some observers of higher education in the Tar Heel State see parallels to what continues to unfold in Florida and elsewhere.

“I don’t think North Carolina is significantly different from the other states where this is a big deal, like Florida and Texas,” former UNC-Chapel Hill Chancellor Holden Thorp, who is now editor-in-chief of Science magazine and watches higher education issues around the country, told The N&O.

There are subtle differences between the higher education landscapes in North Carolina and Florida, though, including that changes here do not appear to be as extreme as those in Florida — at least not yet.

“North Carolina legislators seem to be more careful than Florida legislators,” Jenna Robinson, president of the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, a North Carolina-based conservative education think tank, told The N&O. “They want to draw the line in exactly the right places.”

But some aren’t convinced that North Carolina legislators won’t eventually go to the same lengths as those in Florida.

“My instinct tells me that they’re biding their time,” said Jay Smith, president of the North Carolina chapter of the AAUP, “and the assault is not over.”

Speed of changes in NC has been slower than Florida

In Florida, Republican-led changes to higher education ramped up considerably since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020. With Gov. Ron DeSantis winning reelection in 2022, an array of bills straight from his playbook have passed the Florida legislature just over the past 18 months, as higher education became a centerpiece of his campaign against “woke.”

Republican control of the North Carolina General Assembly — which the party has held since since 2010, and Smith said has made him and other faculty “very concerned ever since” — has led to a trickle of conservative-leaning appointees to university governing boards. That has since intensified after Republicans consolidated appointment powers to those boards among legislators and the legislatively appointed UNC System Board of Governors.

The AAUP has criticized UNC-Chapel Hill and UNC System boards, specifically for political interference and conservative leanings. And Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper last year formed a commission to study university governance and suggest changes, citing what he said were signs of “undue political influence and bureaucratic meddling.”

UNC Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz, who has been “weighing” a decision on whether to leave the university to be the next president of Michigan State University, wrote to faculty there that he would only take the new job if there was no “undue interference” from the university’s governing board.

But politically appointed governing boards and political influences aren’t entirely new on this state’s public campuses. In North Carolina and elsewhere, there has generally always been political input into higher education, Ben-Porath said, because public universities are funded by government funds.

At least some friction over recent higher education policies — both legislation and university-level decisions — in North Carolina has arisen because “the politics of the appointees and the politics of faculty no longer align,” Robinson said.

But Ben-Porath drew a distinct line between differences of opinion over university governance and partisan politics.

“What we need to differentiate is what I see as legitimate efforts to oversee the proper operation of public higher education from the efforts to utilize them to promote electoral, partisan goals,” Ben-Porath said.

Smith said the legislative changes to higher education in North Carolina over the past decade-plus have felt more like “a drip, drip, drip process,” compared to Florida and Texas, “where things are just moving right along” with efforts to alter policies around academic tenure and diversity, equity and inclusion work, for example.

Comparing NC and Florida higher ed policies

Despite differences in pace between the states, this year alone about half a dozen higher education policies and initiatives considered or approved in North Carolina showed similarities to efforts in Florida and other conservative-led states, such as Texas.

Among them:

▪ The proposal and establishment of the School of Civic Life and Leadership at UNC-Chapel Hill, which resembles the Hamilton Center at the University of Florida, established in 2022. The academic units, while officially described by administrators at their respective campuses as a way to foster civil discourse among students, have been criticized for attempting to inject more conservative teaching into universities that are perceived as liberal-leaning.

Dave Boliek, chair of the UNC Board of Trustees when that board endorsed the development of the School of Civic Life in January, said on a Fox News morning show in the days following the board’s action that the school would “remedy” a shortage of “right-of-center views” on the UNC campus. Faculty at UNC criticized the move, noting that the board’s action skirted traditional shared governance structures at the university, in which faculty generally come up with and propose new academic programs.

In the months since the UNC trustees first proposed the school, it has — like the Hamilton Center — received millions of dollars in state funding and been established in state law.

▪ Bans by the Board of Governors and the General Assembly on so-called “compelled speech” in campus admissions and hiring. The policies passed in North Carolina, which prohibit universities and state government from asking or requiring applicants about personal and political beliefs, mirror a Florida law passed this year that prohibits universities from requiring applicants to provide “any statement, pledge, or oath other than to uphold general and federal law.”

The Florida bill that eventually became law was filed in mid-February this year and became effective in July. The Board of Governors introduced its policy for UNC System universities in January, before passing it in February. The North Carolina General Assembly later passed a bill with identical language to that system policy concerning compelled speech, Senate Bill 364, which became law this summer.

Robinson noted that “in many cases,” including on compelled speech, she has “noticed that North Carolina seems to be a little bit more likely to allow the Board of Governors to take the lead on things and not always doing things with legislation,” as has often been the case in Florida.

Though diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) efforts, such as requiring job applicants to describe how they have pursued diversity in their work, were not explicitly named in the North Carolina policies, many have largely been phased out as a result of the measures, The N&O previously reported.

▪ Limits on concepts that can be promoted in state government workplaces. Included in North Carolina’s SB 364 was a list of concepts, mostly tied to racism and sexism, that state employers are prohibited from promoting or including in workplace training. Many of the 13 concepts are nearly identical to those prohibited in Florida’s “Stop WOKE Act,” a 2022 law that has stirred legal opposition.

Florida this year also banned public universities from spending state money on such efforts — a step North Carolina has not taken.

▪ A law requiring public universities and the state’s community colleges to switch accreditation agencies in each 10-year accreditation period. The North Carolina law, passed this summer, is nearly identical to provisions passed in Florida last year.

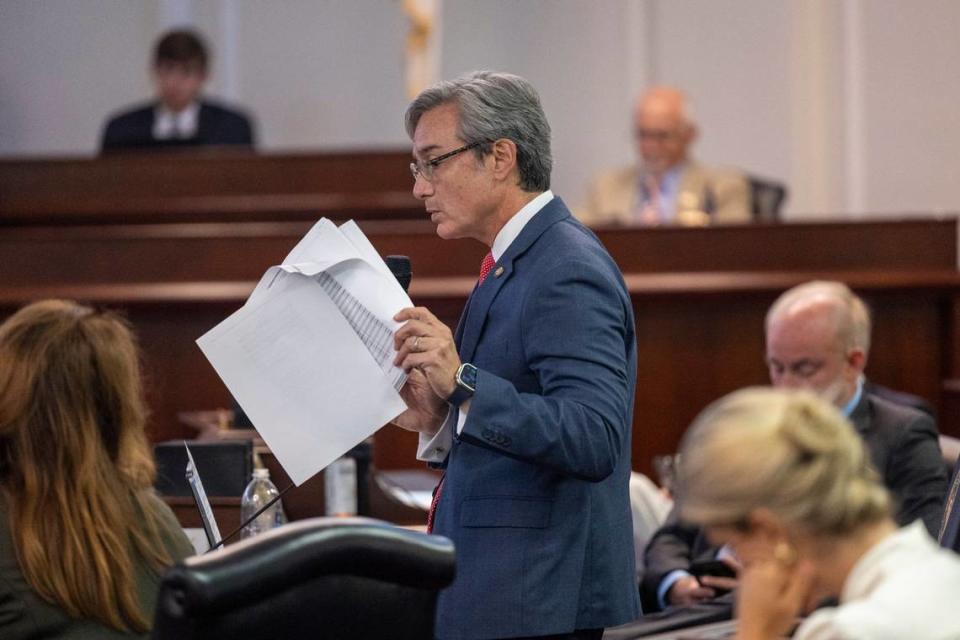

Republican state Sen. Michael Lee, co-chair of the Senate education committee, was a lead sponsor of the original bill, Senate Bill 680, that included the accreditation provisions; the provisions were eventually passed through House Bill 8.

Lee told The N&O that while he was aware of the similar legislation on the issue in Florida, the move stemmed from federal changes in 2019 that allowed universities to use accreditors outside of the regional agencies they had historically been required to use.

“I knew that Florida had similar legislation, although our legislation didn’t necessarily come out of what they were doing,” Lee said. “We were looking at what worked for North Carolina.”

Lee said that “it’s not unusual that legislators will look to other states and see what’s working, what’s not working” on a variety of policy areas, from taxes to education and more.

The similar policies appear to not only flow from Florida to North Carolina. In one case, a newly implemented Florida policy requiring post-tenure reviews for public university faculty bears similarities to the existing UNC System policy on the issue.

The UNC System policy is set to soon undergo its own revisions that system leaders say are intended to make the review process for tenured faculty more consistent across the 16-university system.

Tenure has been a target of legislatures around the country in recent years, with some lawmakers — including some in North Carolina — proposing ending the practice, which is intended to provide academic freedom to faculty, altogether for prospective faculty. The proposal in North Carolina failed this year, as did a similar proposal in Texas.

Calling North Carolina a “reformer” in the national higher education landscape, Robinson noted that the state has led on some issues, such as those concerning “institutional neutrality” — a policy prohibiting public universities from taking a stance on political or social issues, which passed the General Assembly this year. But the state has “been one among several moving in the same direction” on other policies, Robinson said.

National landscape of higher ed

Viewing higher education as a partisan issue — or using it as a partisan tool — is largely a product of increasing polarization in the U.S., Ben-Porath said.

Polls show a widening gap in how people view higher education based on their party affiliation — generally with Republicans having more negative perceptions of universities than their Democratic counterparts, though a July Gallup poll showed confidence had dropped considerably overall.

“We are increasingly distrustful of people in the other camp,” Ben-Porath said. “Our education system gets caught up in that.”

Robinson said education in general, not just higher education, “is extremely salient” as a political issue.

“I don’t think we’re ever going to have someone, you know, thinking actively about the accreditation bill as they’re going to the polls,” Robinson said. “But they do think about the general direction of education, and I think that higher education and K-12 often get lumped together.”

Thorp, who was chancellor at UNC when Republicans gained control of the General Assembly in 2010, said he witnessed North Carolina public higher education become more politicized in North Carolina during his tenure in Chapel Hill. And he has also seen that dynamic unfold across the country since then.

Thorp said national political divisions over “racial dynamics” and social issues are at the center of recent conservative-led changes in public higher education. Those issues rose to prominence following the murder of George Floyd and the racial reckoning of 2020, Thorp observed, though they arose in Chapel Hill even earlier, where the university for years debated over Silent Sam, the Confederate monument that stood on campus until protesters pulled it down in 2018.

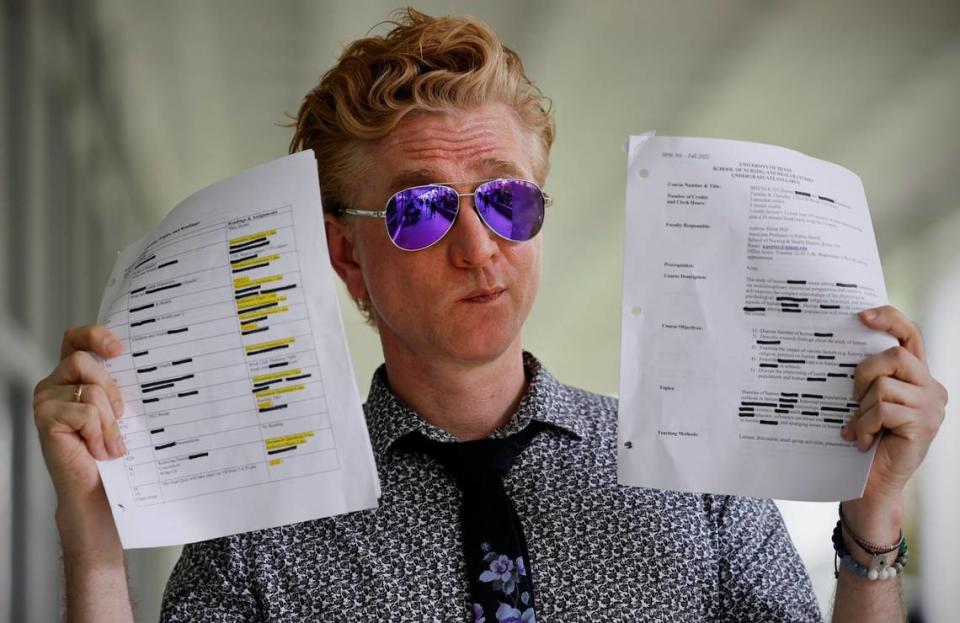

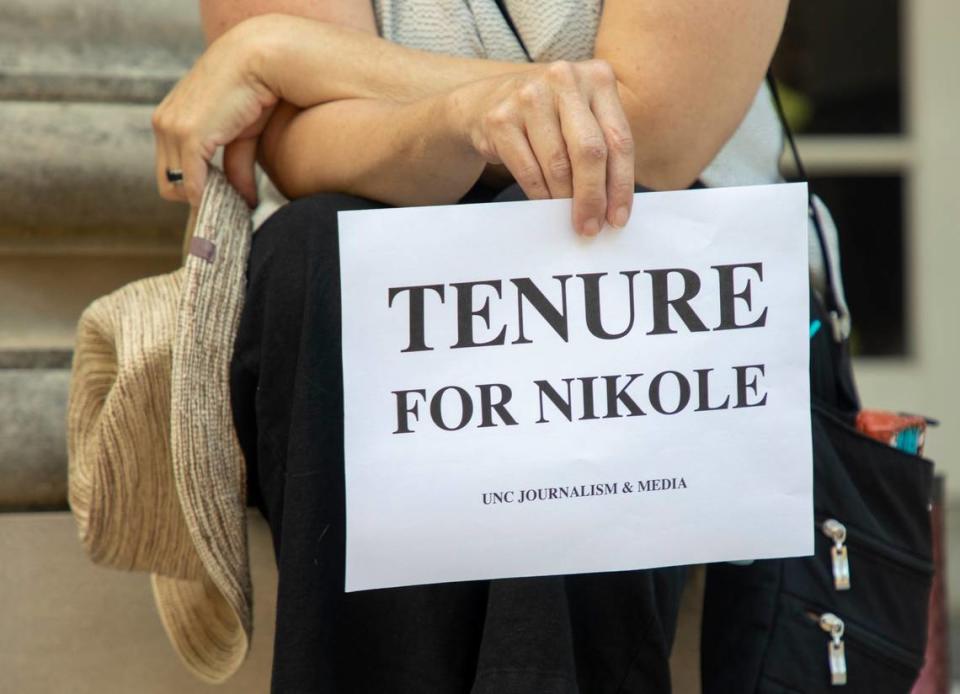

Ben-Porath cited UNC’s initial denial of tenure to journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, author of the Pulitizer Prize winning, African American history-focused “1619 Project,” in 2021 as a key event that further propelled higher education into political conversations not just in North Carolina, but nationally.

Ben-Porath said Florida and North Carolina are two states representing “flashpoints of these struggles, but they are not the only ones, by any means.”

Will NC’s reputation suffer?

Despite ongoing legislative and policy battles in their respective states, North Carolina and Florida’s flagship universities have managed to stay near the top of national rankings of public universities — tying last year at No. 5 in U.S. News & World Report rankings. Rankkings released in September moved UNC to No. 4 and the University of Florida down to No. 6.

Still, the campuses have become battlegrounds over high-stakes and divisive issues, often with faculty and students in opposition to decisions made by governing boards and lawmakers.

The conflicts have come at a cost, particularly among faculty.

More than 1,000 University of Florida employees resigned in 2022, the highest number of resignations for the past five years at the university, according to records obtained by the Tampa Bay Times.

Separate AAUP survey results published in September, focusing on faculty sentiment about the state of higher education in their states, included North Carolina as one of four states where faculty are “deeply dissatisfied,” in part due to political influences on higher education.

Several prominent UNC faculty who have left the university in recent years have cited concerns over political interference as at least part of the reason they departed.

Thorp, who said that “a lot has been lost at UNC in the last 15 years,” noted that the university continues to excel in research and remains prominent among prospective students.

“There are high school juniors all over North Carolina who can’t think about anything except hoping that they can come to Chapel Hill for college,” he said. “They’re always going to be there. There are always going to be out-of-state people who want to come.”

The true impacts of the continued battles over higher education policies in North Carolina will be seen, Thorp said, in “whether there are still young faculty who really want to come to Chapel Hill and build their careers” and whether the university continues to stand out among other universities across the country.

“It’s painful to watch for those of us who believed in the ideals that were there before, but [Republicans] won the elections and they have the power to do most of these things,” Thorp said. “And, you know, everybody needs to buckle up and realize that it’s not going to get any easier anytime soon.”