What Happens When a Car Dies? We Send a 3-series to the Shredder to Find Out

If you wish to make it through this violent, ugly story, it’s best to stop thinking of an automobile as a living thing with “personality” and a “soul,” as we so often do in this magazine when we indulge in our pet hobby of gratuitous anthropomorphism.

Instead, look at our cheerful little 1993 BMW 325i—no, stop; it was not cheerful; it did not live, so therefore it cannot die—the way the auto-recycling industry sees it.

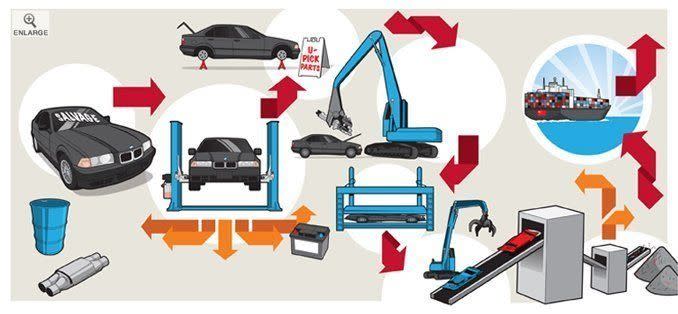

Once drivers are finished extracting the bulk of a car’s value, the salvage industry steps in to milk out the final few dollars. To an industry that scrapped roughly 11.7 million cars last year, our BMW is just 3100 pounds of steel, aluminum, plastic, glass, rubber, leather, zinc, lead, silicon, oil, antifreeze, and refrigerant. Each component represents a positive value in material or a negative in disposal cost, all of which is calculated down to the half-cent per ton or gallon on a ledger that fluctuates almost daily with global spot commodity prices.

As in a slaughterhouse, the sorting of a whole car into its valuable cuts is not pretty, so keep reminding yourself that this is a natural, continuous, and highly capitalistic cycle of replenishment that is good for society and the environment. At least, we’re pretty sure it is.

We found our BMW lurking in the back of the lot at Blok Charity Auto Clearance in Gardena, California. Blok specializes in liquidating cars that have been donated to causes. The prices are consequently modest.

This black 325i automatic showed 210,909 miles turned on L.A.’s pitiless streets and was branded with the scarlet letter of a salvage title, meaning it had already been crashed severely enough to have been written off by an insurance company and then rebuilt to unknown (and likely dubious) standards. The 189-hp, 2.5-liter inline-six ran evenly but percussively due to its tick-tickety valvetrain and loose, slapping pistons. The rear wheel bearings howled in despair. A battered front bumper hung by a few fasteners, the leather buckets were split, and black tape held the door trim together. After some grimacing, Blok let it go for $1300. (The salvage yard told us later that it wouldn’t have paid more than $400.)

Nathan Adlen and his cousin Andrew run Aadlen Bros. Auto Wrecking (note the spelling difference) in Sun Valley just north of Los Angeles, where it was started by Nathan’s dad in 1962 and christened with an extra “A” to move it higher in the phone book. With Hollywood as a neighbor, the 26-acre scrap yard has been used in many film shoots, and it has a funky, only-in-L.A. ambience supplied by a collection of decorative junk ranging from missile launchers to a sunburned Citroën SM to “Bruce,” one of the mechanical sharks from the movie Jaws.

The place is all business, however, built around the notion that $400 crap heaps, acquired mainly through auctions and “Junk Cars Wanted” ads, can yield $500 to $800 in revenue through the punctilious salvaging of every morsel of their recyclable material, up to and including the license plates. At any one time, Aadlen’s Sun Valley yard (it has another in L.A.) contains about 1500 derelicts. The spread includes an eerily clean and well-organized domestic-vehicle self-service lot and, as you’d imagine in L.A., a substantially busier and more lucrative foreign-vehicle lot, where citizens can come and scavenge their own parts.

Despite its age and Oliver Twist existence, our BMW made it into the yard still burning gas in most of its cylinders and still exhibiting faint traces of the endearing dynamics that made the E36 3-series a Car and Driver 10Best winner from 1992 to 1998—every year it was in production.

Aadlen manager Jorge Trujillo started our BMW on its final journey by filling out a “death certificate,” a form that registers the car’s scrapping with the state as well as the Department of Justice, which, since 2009, has required every dismantler to report scrap cars to its National Motor Vehicle Title Information System. This was created to discourage theft and title washing.

One of Aadlen’s 85 employees then came along with a cart and yanked the BMW’s battery and drained the brake-fluid and coolant reservoirs. The battery will earn up to $15 for its lead, plastic, and acid. The brake fluid will be mixed with motor oil and other lubricants and sold to recyclers.

Trujillo figures Aadlen recoups about 95 percent of the oil that comes in the door, for which the yard is paid 30 cents per gallon by the recyclers and another 16 cents per gallon by the state as an incentive against dumping. The rest ends up in absorbent kitty litter or goes out the door still clinging to parts. Every month, Aadlen Bros. collects and ships out 5000 gallons of gasoline, 2500 gallons of waste oil, and 1700 gallons of antifreeze, and it processes most of its stock of car bodies.

Next, a giant Volvo front-end loader trundled in to scoop up the BMW as easily as if it were Barbie’s Corvette, placing it on an overhead rack. There, a worker cut out the car’s catalytic converter. Trujillo’s face fell when he saw that it was an aftermarket part, worth only about $7. An original BMW converter can fetch up to $250 for its platinum and other precious metals.

“Prices are high; there’s a strike right now at a mine in South Africa,” he said. “That’s music to our ears.”

A special spill-proof drill punctured the gas tank and drained the fuel. Out went the transmission and differential lubes, as well as the remaining coolant and air-conditioning refrigerant, which are recycled. Once the vital fluids were drained, the BMW was carried off by the loader to the U-Pick Parts lot, where it would normally sit for a month and generate, on average, about $150 in sales. Usable tires are sold in the lot’s tire shop; worn tires earn $2 apiece from a vendor who sells them on the street to, apparently, desperate people.

We didn’t have a month to wait, so we took pictures and shuffled the Bimmer on to the next step, which is where things turned especially gruesome.

About a year ago, Aadlen replaced its old dismantler with a $100,000 hydraulic shear that looks like a giant steel lobster claw. It fits to the end of a $200,000 excavator and swings around and rotates and gnashes its pincers like something Sinbad would fight in the 21st century.

Operator Alejandro Hernandez delicately grabbed our BMW by its roof, lofted it into the air, and brought it into his den, where in swift and terrifyingly violent strokes, he peeled off the hood and yanked out the aluminum radiator with a nauseating crunch. The little BMW shuddered. Then the claw dived in and ripped out the engine and transmission whole, tossing it on a stack like a chicken bone. Was it a faint scream we heard, or just the rending of metal?

The claw wasn’t done. With a precise thrust, it smashed through the windshield and cut the dashboard in half, giving workers down the line access to the copper wiring harness and electronic boxes. In less than two minutes, our BMW was gutted, its remaining entrails spilling out in a grotesque tangle. The wiring and electronics were then cut out by hand to be recycled separately. The engine and transmission assembly will be shipped to South Korea, where buyers pay Aadlen 25 cents per pound for the high-quality metal.

Having yielded their hearts and brains, the cars are just husks at this point. The loader carried ours to Aadlen’s 159-ton press, which, in 30 seconds, compressed the BMW to a height of about two feet for easier transport to the shredder located 40 miles away in Anaheim. It’s just a car. It was just a car. It felt no pain. We kept repeating that to ourselves to ward off the tinges of guilt and the spectral murmurs from all the engineers, designers, and owners for whom this car was more than just grist.

At SA Recycling, about seven miles from the gates of Disneyland, our BMW joined a towering pile of cars, trucks, city buses, rail cars, washing machines, hot tubs, golf clubs, office furniture, and the rest of Los Angeles’s prodigious daily output of metal flotsam. An excavator with a massive four-fingered claw picked up the car and placed it on a conveyor, which carried it on its final trip, up to a three-story-high precipice from which it slid down into a giant steel drum of pulverizing hammers.

Spun at 450 rpm by a 7000-hp electric motor, the shredder is able to chew through 200 tons of refuse an hour, reducing everything that a throwaway society can throw into it down to chips no larger than 6.5 inches long. Magnets extract the ferrous metal, grates swallow the nonferrous, and the remainder, which the industry calls “ASR,” for auto-shredder residue (or “fluff”), is treated with neutralizing chemicals and sent to a landfill.

The BMW 325i once known as WBACB 4314PFL05766, dismantled with repetitive indifference by hourly workers, dropped as hundreds of small metal chunks onto a pile that was packed into 20-foot containers, trucked to one of L.A.’s two ports, and loaded onto a ship headed, most likely, to China. Someday it may return as rolls of steel coil for new cars or maybe as lawn chairs for Walmart; only God knows.

Meanwhile, if you own an older car—and especially one of the now marginally more valuable E36s—take this opportunity to ponder the fate from which you are saving it and go out and give it an oil change and a hug. It’s just a car, but it will thank you.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos