Happy birthday, Dennis the Menace – you're a true British rebel

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

He was born 10 years old, in a pub, on the back of a pack of cigarettes, with unruly hair, knobbly knees and a scowl. And, on 12 March 1951, Dennis the Menace sneaked onto a half page of The Beano, as the “world’s naughtiest boy”. Soon, his popularity would make him the comic’s cover star. Now, 70 years later, he’s still going strong – not a day older, still at school, and as badly behaved as ever.

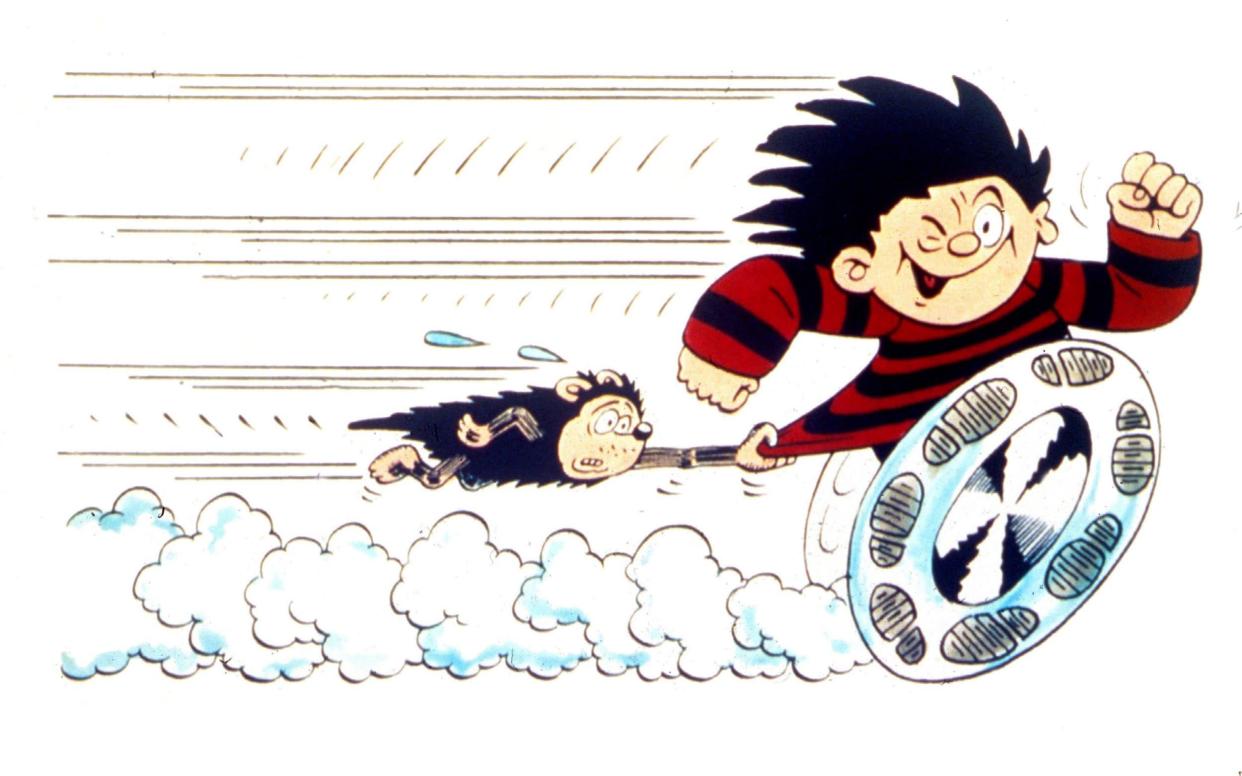

Of course, he no longer uses his peashooter and catapult these days, for fear he might put someone’s eye out, but his mischievous spirit is undimmed. As the first naughty kid in British comics, Dennis the Menace began a trend – he was followed by Beryl the Peril, the Bash Street Kids and Minnie the Minx – terrors all. But Dennis, in his black and red striped jumper, retains a special place in our affections. Even more so because he never learned a thing from his mistakes. As the former children’s laureate Michael Rosen once put it, “In most children’s books, a bad child gets made good – but the great thing about Dennis is he never gets better.”

This taps into something significant: the roots of our love for Dennis the Menace run deep. The urge to rebel against authority – and to remain unbowed by it – connects with something that goes way back into our pagan past. There dwells an impish spirit that can be traced through our history, finding its way into tales of prank-pulling brownies and troublesome nature spirits like Puck, or Robin Goodfellow, who turns up in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and on and on, into Mark Rylance’s tale-spinning Johnny “Rooster” Byron in Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem.

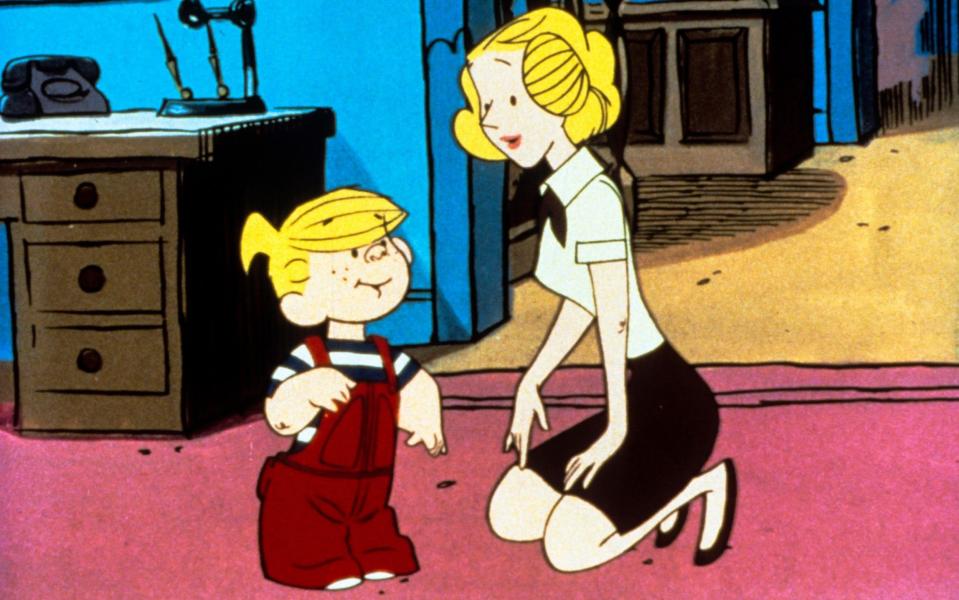

It’s a deep, dark pool that separates Dennis the Menace from his American counterpart – an entirely different character, who debuted in the same year – much more profoundly than the ocean that divides us. Theirs is a loveable kid with a cowlick, essentially well-meaning, altogether more bland. Our Dennis is a thorn in the side of authority, wherever he finds it.

The very first time Dennis the Menace appeared in print, he was confronted with a “Keep off the Grass” sign. He was determined to ignore it. Of course he was! From the suffragettes to the overturning of the poll tax, there is a long history of recalcitrant Brits questioning the power of others over them. The groundswell of support for Brexit could be summed up by the phrase: “Don’t tell us what to do.” In the eyes of Leavers, the whole EU law-making apparatus could be characterised as one giant “Keep off the Grass” sign.

Yet Dennis also loves mischief for its own sake, for the sheer joy of it. And that impulse had been breaking through into children’s literature for quite some time. In a recent essay for the British Library, Andy Stanton described how the 15th-century tome The Lyttle Childrens Lytil Boke was lyttle more than a tedious list of dos and don’ts – “Pyke notte thyne errys nothyr thy nostrellys” hardly needs translation (it’s ears, just in case you had a worse thought). But, the essay continues, as the cautionary tales intended to teach children to behave became more sophisticated, by the 18th and 19th century, their stories began to seem like fun. Characters such as Sulky Sue and careless Jacky Jingle may have faced punishment and misfortune for their failings, but at least they had personality.

By 1922, Richmal Crompton’s Just William books gave children an openly mischievous, and hilarious, hero. Dennis the Menace would surely have admired the way William knocked his father into the bushes in his very first adventure, William Goes to the Pictures, while pretending to be a crook from a film trying to escape from the police. Since then, children’s literature has given us My Naughty Little Sister, Horrid Henry, Roald Dahl’s Matilda, David Walliams’s The World’s Worst Children. Lauren Child’s Clarice Bean may never have remarked on her teacher’s “big derriere” had Dennis not already blazed a trail of outrageous behaviour for her.

Ronald Searle’s original St Trinian’s girls, I might add, were so bad most of the time – with sadists for teachers – that even most adults today would be horrified by them. The fact that they started life as a comic-strip in a magazine, though, ensured that they had a vivid, clearly defined look.

Dennis has one, too. The comic-book medium demands that the visual component of storytelling is paramount. And Dennis has style. He ditched the shirt and tie he wore in his early days, but his fashion choices have not changed since. He was a punk before the Sex Pistols were even heard of, and not just in his love of anarchy. Their comic-book names sounded a lot like his and they even stole his look. Pistols’ manager Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood sold striped mohair sweaters from their shop Seditionaries back in 1976. Johnny Rotten wore one, and he and Sid Vicious both stuck their hair up in spikes, just like Dennis. They probably had knobbly knees, too.

Yet Johnny Rotten showed us something else about Dennis the Menace – just how strongly Brits respond to people who look and behave like cartoons, from Ken Dodd to Keith Flint of the Prodigy, with his neon devil-horn hairdo and studded tongue. The lines of the hit single Firestarter could have been written by Dennis: “I’m the trouble starter/ punkin’ instigator”.

The conjunction of a cartoon public image with an anti-authority stance clearly still connects with something in the British psyche. Would Dominic Cummings have had such an impact on the nation’s front pages if he didn’t dress like someone who’d run off with a charity shop mannequin in the dark? I doubt it.

Over the years, Dennis has changed a little. He used to target the Softies, which seems like bullying now, and they’ve learned to fight back. But his essential nature – contrary, disobedient, creative, inventive and naughty just for the fun of it – sounds an awful lot like a description of the British character. It’s only another 30 years before he gets a telegram from the Palace. I wonder what he’ll do with it.

The Dennis the Menace anniversary edition is out now