Happy and painful memories for Jacksonville family that tried to restore 'Hitler's yacht'

Horace Glass says his motivation to save the Ostwind, a Germany boat known widely as "Hitler's yacht," was simple.

"I couldn’t stand to see such a fine yacht destroyed," Glass, who's 88 and living in Plymouth, N.C., said in an interview Wednesday with The Florida Times-Union. "We did our best to save it.”

For more than 11 years in Jacksonville, beginning in 1971, he tried to restore the Ostwind, raising it from the muck of the Intracoastal Waterway, pouring time and money into saving it, and fending off offers from American Nazis to buy it ("I would open her sea cocks rather than sell her to them," he once said) — only to see it fall prey to the elements, to vandals and to the steady march of time.

Read more: 'Hitler's yacht' spent almost 18 years in Jacksonville and was nothing but trouble

'A very sad time'

The story caught the public imagination, back in the 1970s and '80s and attracted much attention in the media, though Glass insists: “A lot of the stuff that was published was inaccurate."

He made several trips to Germany to research the yacht's history and is sure that Hitler had more connection to it than some believed. “He was on it either 12 or 13 times," Glass said of Hitler. "Of course, he always had his girlfriend with him, Eva Braun.”

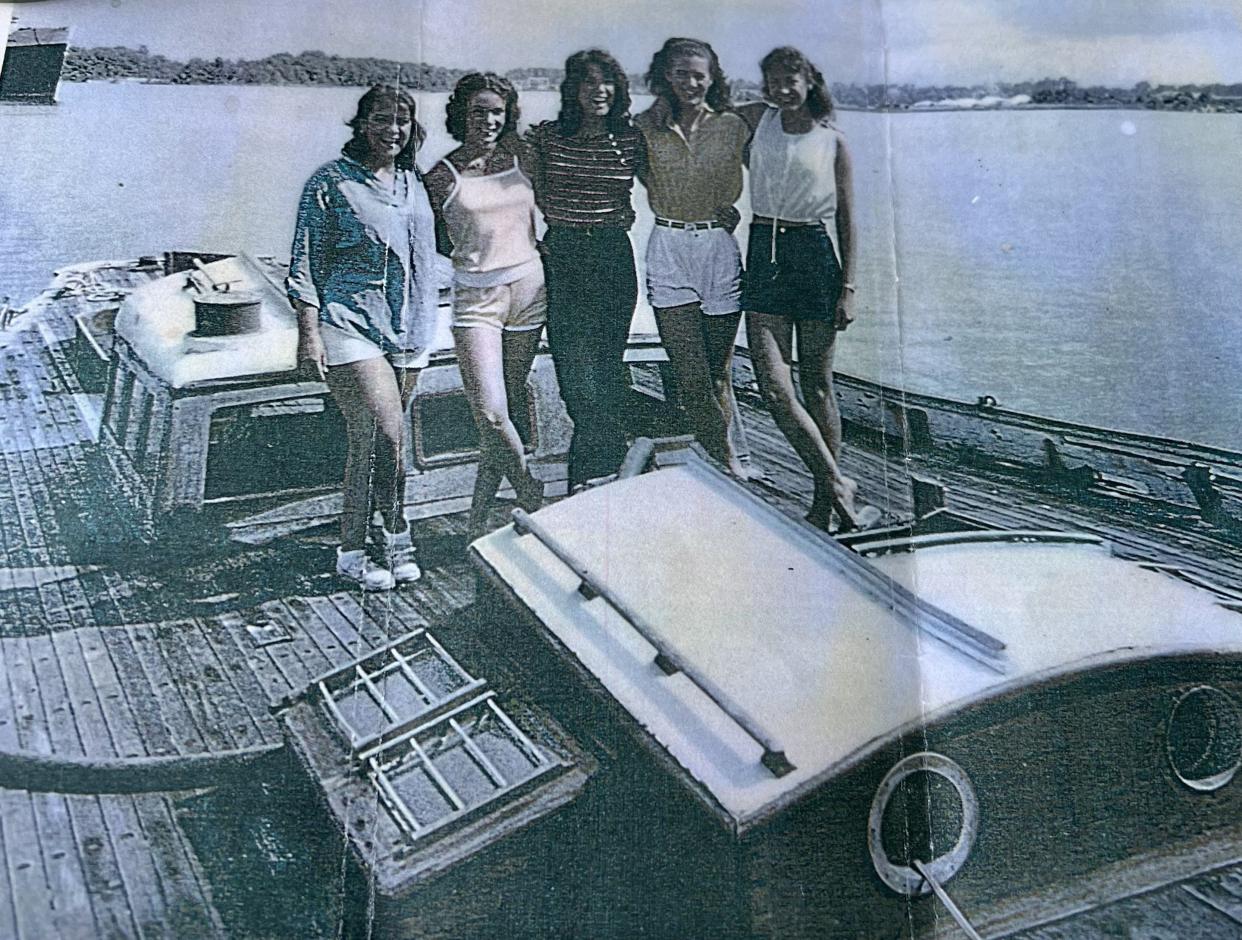

Glass said much of the repair work on the Ostwind fell to his five daughters, who spent countless hours aboard.

The eldest daughter, Debi Everett, still lives in Jacksonville and said there were some real high points in trying to repair the yacht.

German history: Rare pictures of Hitler emerge from glass photo negatives, like parts of a puzzle

“The Ostwind story was some great times," she told the Times-Union last month. "We had great times, learned a lot; it just didn’t work out."

But chasing that dream became a "full-time occupation," one reporter wrote, while another noted that the Glasses "gave up a commercial art and advertising business and eventually sold three houses, two from previous marriages, to pour everything into restoring the yacht.”

Everett states it flatly. "It became a very sad time for me," she said.

Glass, meanwhile, said he had no regrets. "No, none at all.”

A dreamer

Everett describes her father as a free spirit, "an old hippie," someone who didn't want to work for anyone else.

"He is an artist, and a dreamer," she said, "and I think he thought it would make a great home for him and his girls. And once he found out about the history of it, it was, 'Oh, this would be a good museum.'”

As for the challenges of taking on the Ostwind?

He was a graphic artist, a writer, publisher of a community newspaper: Good skills, but not much related to restoring a once-luxurious vintage German yacht.

That didn't faze him, his daughter said. "He is amazing. He's the king of make-do; he can figure something out, figure out how to make it work in a jury-rigged situation, and make it work, with no money.”

One early story from the Glass family's Ostwind days makes that clear. He'd heard the boat was mostly sunk in the Intracoastal Waterway and wanted to lay eyes on it. That meant scuba diving to it.

Fact check: Time magazine did not praise Hitler with 1938 'Man of the Year' title

'The American way': The battle for Ukraine and why it matters to the U.S. and the world

To be sure, he'd grown up on the St. Johns River in Jacksonville's Mandarin neighborhood, descended from one of that area's oldest families, the Reads, and he'd spent plenty of time swimming and diving.

Just one problem: He didn't know how to scuba. But he didn't let that stop him.

"Diving was nothing new to me, but scuba certainly was," he said. "I borrowed a scuba set from a friend, and as we drove down there I had my wife Jody read a book [on scuba diving] — to tell me what not to do.”

That's how much of the work went, Everett said. “We learned as we went, there was no YouTube or Google," she said. "It was books.”

Everett is 65 now, married 42 years, with four children. She's moved on, a long way, from the Ostwind story, but still has plenty of memories.

“Some of it's painful, some of it's happy," she said.

It's suggested to her that the family's story with the Ostwind seems as if it could have been turned into a movie or TV show.

She gave a dry laugh. “Maybe it should have a happier ending," she said.

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Jacksonville family for years tried to restore Hitler's yacht, Ostwind