It’s hard to say goodbye to a family friend | Holly Christensen

This past January, my longtime friend Jen, who is my regular traveling companion and has made several appearances in these columns, called to tell me her father would soon die.

Several years ago, Mr. Tressler was diagnosed with early-stage Alzheimer's. And, yet, he seemed himself when Jen and I talked to him on the phone in May 2021 while we toured Iceland and again later that year when we went to Peru.

In January 2022, Jen, who lives in Philadelphia, spent two weeks with her parents' at their home in Painesville, where they've lived since 1980. She, her dad and her eldest daughter came to Akron to shop at their favorite thrift store, Village Discount Outlet on Waterloo, and visit me.

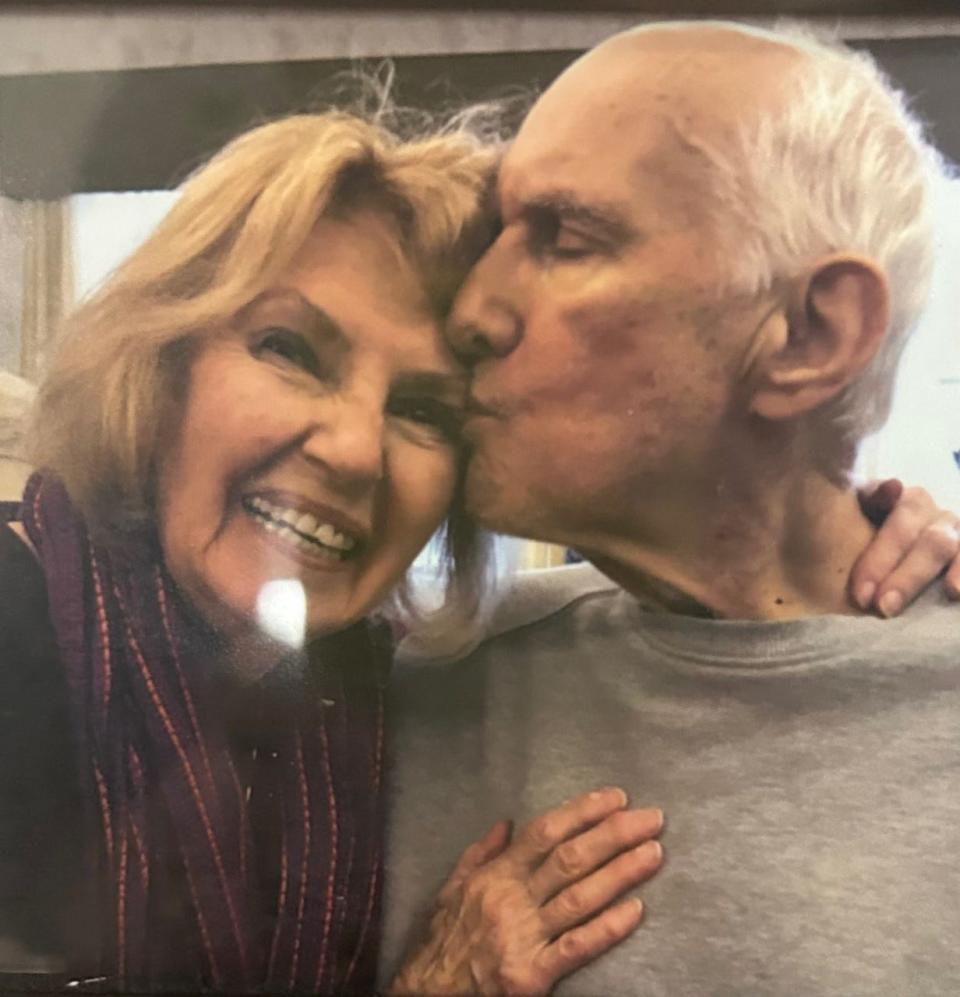

Over lunch at my home, Mr. Tressler recounted various times over three decades that he and I had visited, both with and without Jen. I had forgotten several of these accounts until he shared them. That I was in his long-term memories when he was no longer able to write his own name was an honor unlike any other.

Jen's job as a triage nurse for a medical practice at the University of Pennsylvania periodically allowed her to work remotely. Every month or two, she'd come to Ohio to spend a week helping her family take care of her dad while also spending increasingly precious time with him.

During one of her stays late last spring, I drove my youngest two kids to Painesville where we spent the afternoon and dinner with Jen and her family.

Mr. Tressler seemed unchanged from January and, again, we talked of many things. While dishing up bowls of ice cream, he showed me his significant collection of ice cream scoops. Upon learning I had none, he gave me one.

Two months later, Mr. Tressler's Alzheimer's specialists told the family he was beginning to decompensate and would soon need full-time care. Jen and I were shocked, but like Delphi oracles, the specialists were tragically correct.

When Jen called this past January, I asked if her mother would be OK if I visited Mr. Tressler at Kemper House, where he was living. Some families prefer their loved one with Alzheimer's to be remembered as they were without the disease. And, too, some people with Alzheimer's are agitated by visits.

Mrs. Tressler told Jen she welcomed my visit, but then, just two days later and before I could make the trip, Mr. Tressler died.

I first introduced readers to Jen when I wrote of the 14 months that she, her husband, Milan, and their four daughters circumnavigated the globe beginning in August 2015. This past fall, after their two eldest daughters had graduated from college and high school, the family again left the country, this time to tour Central America and South America for several months.

They were in Patagonia, at the southernmost tip of South America, when Mr. Tressler died. Returning in time for the funeral proved overly complicated and costly. On my drive to the funeral, Jen called and asked if I could so something neither of us would have thought of before the pandemic: Zoom her into her dad's funeral.

Jen's mother, siblings and their spouses sat in the first row of pews at St. Gabriel's Catholic Church in Concord. I sat behind them in the second row, holding my phone up so Jen could see and hear their parish priest perform the funeral rites.

Before he developed Alzheimer's, Mr. Tressler could be described as gruff. He grew up in a working-class Ukrainian community in Reading, Pennsylvania, and married his sweetheart soon after they finished high school. He worked hard every day of his life and didn't suffer nonsense. But he could also assess a person's character with mystical accuracy. And if he found you measured up, you could forever count on him.

After Mr. Tressler's. death, Jen and her siblings learned of their father's unadvertised history of generosity. The people he helped and how he helped them revealed a man who understood firsthand what it meant to have little and that being poor is not a character flaw.

The priest shared many stories of Mr. Tressler's quiet largesse, including the time he arranged and paid for the dental work for the city worker who collected the family's trash each week.

Far too many people past the age of 30 have experienced the vicissitudes of a friend or family member losing their memories, personalities and lives to Alzheimer's disease.

But, as I have shared in previous columns, current Alzheimer's research is promising. Studies around the world, including those focused on people with Down syndrome, look to yield preventative and corrective treatments in the coming years. That is something everyone can welcome.

Contact Holly Christensen at whoopsiepiggle@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Memories of a good man are cherished