Harriet Beecher Stowe and abolitionists wrote of the glory of Florida, calling Yankees hither

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Many histories of Florida point to the 1880s as the start of serious tourism in Jacksonville and across the state. That's not so, says John T. Foster Jr., a professor emeritus at Florida A&M University who graduated from the Beaches' Fletcher High School in 1964.

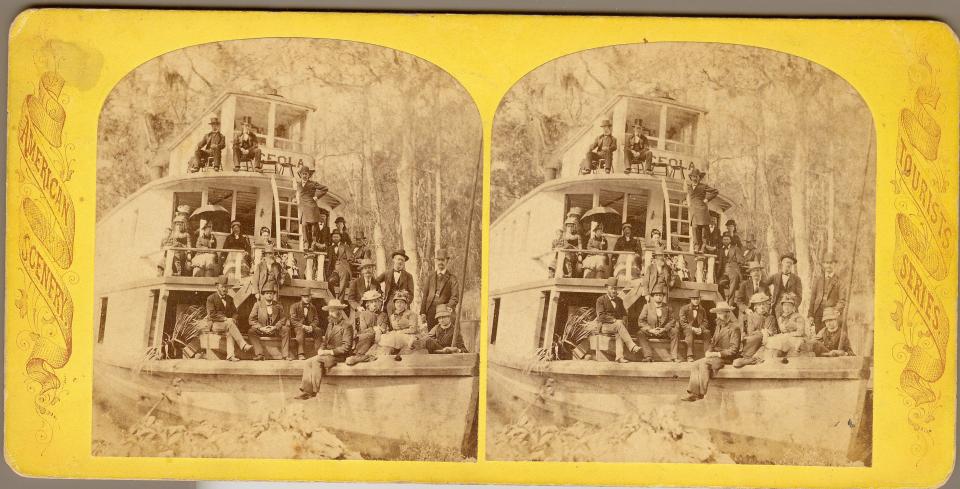

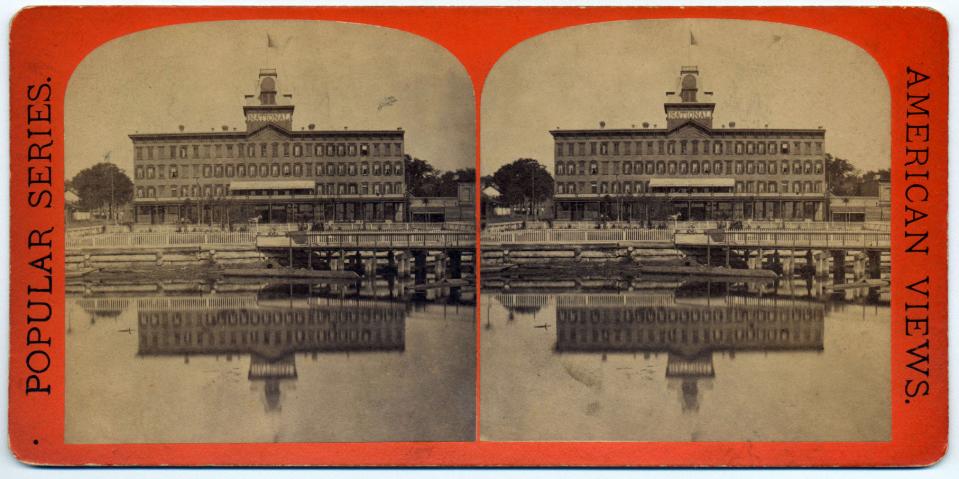

Instead, says Foster, it began a decade or more earlier — a phenomenon fueled in large part by three noted abolitionists who had a very real motive in promoting the image of Florida as a paradise. Basically they wanted to make Florida more Northern in its thinking, and less tied to the South of the Confederacy.

Jacksonville's bicentennial: What were the biggest turning points in city's history?

Those abolitionists were Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of "Uncle Tom's Cabin" and a hugely famous and influential person whose winter cabin on the St. Johns River in Mandarin became a tourist stop in its own right.

Another was Northern Methodist minister John Sanford Swaim, who had moved to Jacksonville for his health. The third was William Cullen Bryant, a renowned poet and journalist.

Mark Woods: Harriet Beecher Stowe unpaved the way for women to protect Old Florida

After 200 years: Here's a checklist of names from Jacksonville's history

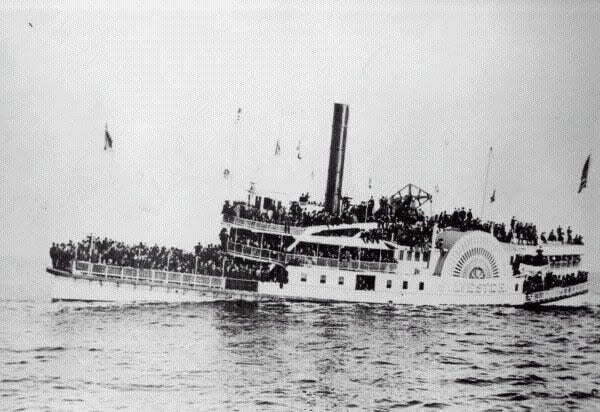

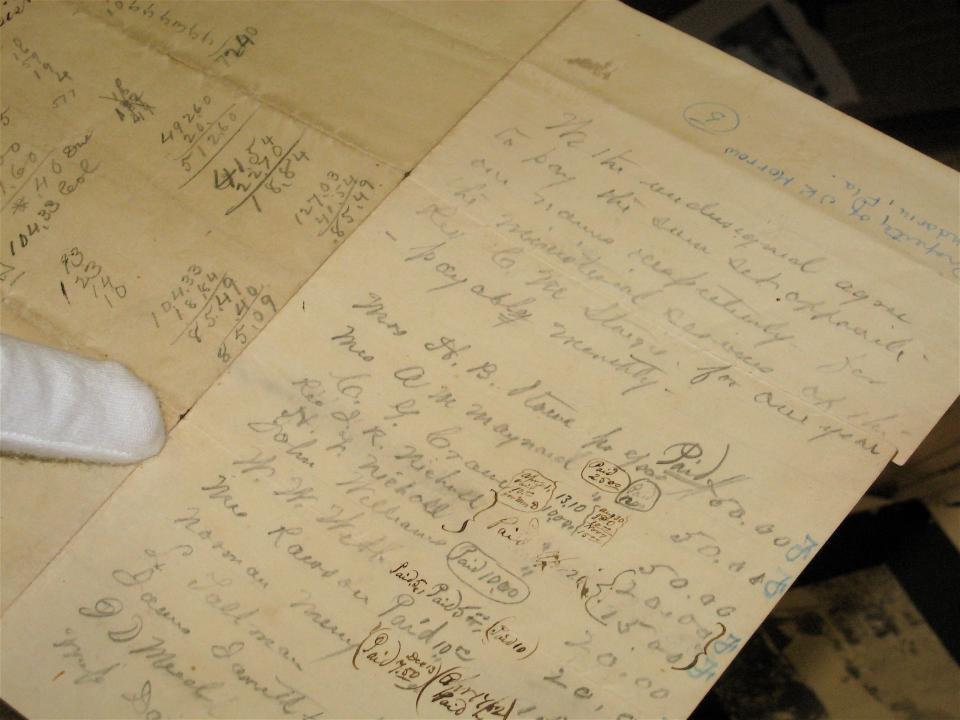

They published widely read books or articles in Northern newspapers extolling both the beauty and the business possibilities to be found in Florida. They had an influence, says Foster, who points to news accounts in 1874 saying Florida had seen 50,000 visitors during the previous season.

"You can imagine what that would have been like for a state of less than 200,000 residents,” he says.

In a brief paper, Foster writes: "The abolitionists had an ulterior motive for launching this vast Florida tourism publicity campaign. Their intent was to create a place of genuine freedom for all Americans. A new economy based upon tourism, new residents from the North, and cultivating novel agricultural crops, especially citrus, would offer a world of opportunities. As these developments unfolded, African Americans thrived in a far less racist environment."

Local history: Celebrate Harriet Beecher Stowe's legacy in Jacksonville

The rich history of Jacksonville: The one you probably didn't know about

He writes of their efforts in two books published by the Florida Historical Society in 2019: "Calling Yankees to Florida: Harriet Beecher Stowe's Forgotten Tourist Articles" (written with his late wife, Sarah Whitmer Foster), and "At the Dawn of Tourism in Florida: Abolitionists, Print Media, and Images for Early Vacationers."

Scott Matthews, who's creating a Jacksonville history course for Florida State College at Jacksonville, will include Foster's work in a discussion of Emancipation and Reconstruction during the 1860s through the 1880s.

Local history: FSCJ course on history of Jacksonville, a city at the crossroads, will be open to public

At 200, Jacksonville has old problems: Can their lessons help tackle tomorrow's issues?

Foster and Matthews say the effort of the abolitionists worked, for a while, in Jacksonville in particular where during Reconstruction the city's large Black population had opportunities for education and advancement not found in other Southern cities.

Alexander Darnes: Jacksonville's first black doctor, Confederate general had close ties

George Edwin Taylor: Presidential candidate, son of a slave, made Jacksonville his last home

That didn't last, however, notes Matthews: “From the very beginning there was tension with local whites and Northern migrants and missionaries. That was not unique to Jacksonville. There was that image of the quintessential carpetbagger, the Northerner who was coming down and telling how they were going to remake society in this more enlightened vision."

The abolitionists' efforts were for the most part written out of Florida history, Foster says, as generations of South historians ignored them and pegged the start of tourism to the 1880s — something he calls "the big lie."

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Harriet Beecher Stowe and others wrote of Florida's beauty