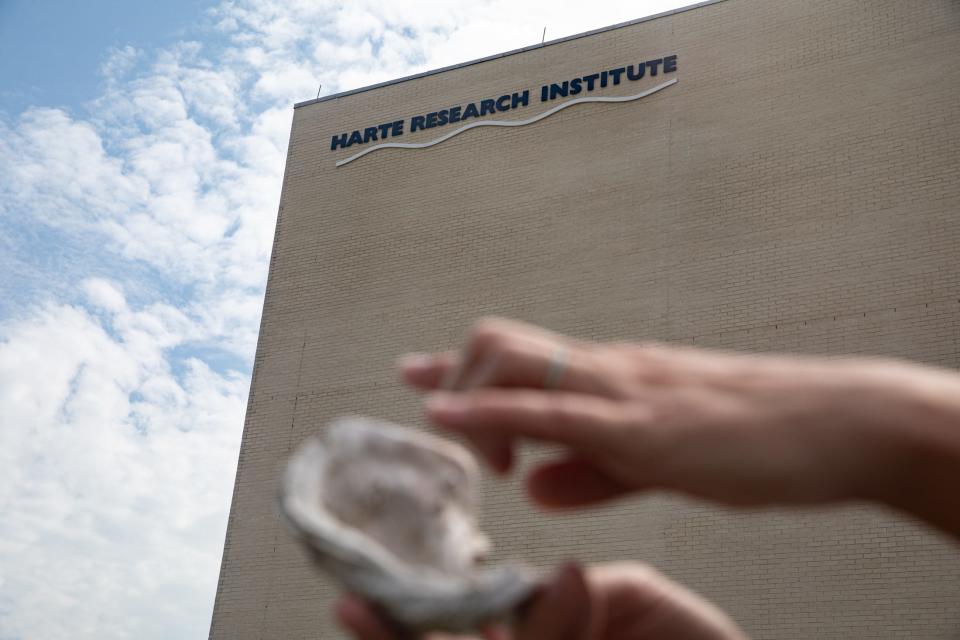

Harte Research Institute eyes new waters after St. Charles Bay oyster restorations

Five years in, local conservation efforts have transformed the oyster reefs of St. Charles Bay. Now, the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies team is eyeing other local bays.

Oysters need reefs made of oyster shells to settle and grow on. Because oysters are removed from the water with their shells, the oyster habitat is harvested along with the oysters themselves.

The group, working with the Coastal Conservation Association, Derrick Construction and Goose Island State Park, has focused on bays near Corpus Christi that the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department has closed to oyster harvest, including St. Charles Bay and the Mesquite Bay complex, north of Aransas Bay.

“By restoring those reefs in these sanctuary areas, you’re protecting the adult oysters that can produce millions and millions of baby oysters that can come out and provide a supplement to reefs in other areas, including areas that are harvested,” HRI endowed chair for coastal conservation and restoration Jennifer Pollack said. “So, it’s an indirect benefit to all reefs.”

Oysters reproduce by producing planktonic larvae that float around in the water for two or three weeks, Pollack said.

"Because of the currents in those (bay) systems, those little baby oysters get transported all throughout the bay, and that includes areas that are harvested outside of St. Charles Bay, for example in the adjacent Aransas Bay,” Pollack said.

Oysters live all along the Texas coast, in the Galveston, Aransas, San Antonio, Matagorda and Corpus Christi bays.

Oysters are moderate salinity organisms, typically found in the upper bay areas, said Zachary Olsen, the Aransas Bay ecosystem leader of the Coastal Fisheries Division of Texas Parks and Wildlife.

The state closes certain areas to harvest based on oyster size and breeding in reefs. The Mesquite Bay complex, including Carlos and Ayres bays, was closed to harvest in 2022 after fishing pressure increased in the area.

Oysters are filter-feeders, Pollack said, cleaning and clearing bay waters.

“One adult oyster can filter up to 60 gallons of water in a day,” Pollack said. “You have thousands and thousands of new oysters that establish themselves on these reefs.”

Oyster reefs also protect the shoreline from erosion and increase biodiversity, creating a habitat for other organisms.

“It supports recreation and tourism in Texas because you can go out there any time of day and you see people wade-fishing and kayak fishing,” Pollack said. “(Reefs) bring in the larger sportfish because they feed on the little organisms that live in the nooks and crannies of the oyster reef.”

Additionally, oyster reefs can play a role in capturing and storing carbon, Pollack said.

“We’re trying to start to understand what a habitat like an oyster reef can do to help to reduce some of the excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and reduce some of the carbon footprint,” Pollack said.

St. Charles Bay project

The HRI St. Charles Bay project began just weeks before Hurricane Harvey in St. Charles Bay after the state closed it to harvest in 2017.

“We were really terrified that we had just finished building this reef and it was a considerable investment of people’s time and the hurricane passed right over that area in Rockport,” Pollack said. “It took us about a month after the storm to be able to get back out there and monitor the reef.”

When the team made it out to check on the restored reef, they were amazed.

“The reef was intact, which was the thing that we were most scared about,” Pollack said. “The reef looked great. And, because the salinity of the bay dropped because of all the rainfall in the area, we think it caused the natural populations of oysters nearby to spawn.”

The restored reef was not only intact, but it also had a whole new generation of baby oysters.

The team has since restored more than 20 acres of reef in St. Charles Bay.

The Coastal Conservation Association has helped fund the effort, along with other oyster restoration and conservation efforts across the state.

“They might not be the beauty queen of the ecosystem, but they’re hugely important,” CCA Texas assistant director John Blaha said. “...we’re going to continue this effort to ensure that (oysters) are a sustainable resource for the local ecosystems for all user groups.”

Pollack said the efforts in St. Charles Bay have been extremely successful, with oysters and biodiversity returning to the area.

Now, the group’s focus is shifting to nearby Mesquite, Carlos and Ayres bays, which were closed to harvest in 2022.

“We can use the same sort of approach to rebuild areas that have been degraded,” Pollack said. “It provides a nice transferable solution into the bay system right around the corner that’s now just recently been closed.”

The team will continue working with Goose Island State Park for community-based oyster restoration events in St. Charles Bay, but it is shifting large scale efforts to the Mesquite Bay complex.

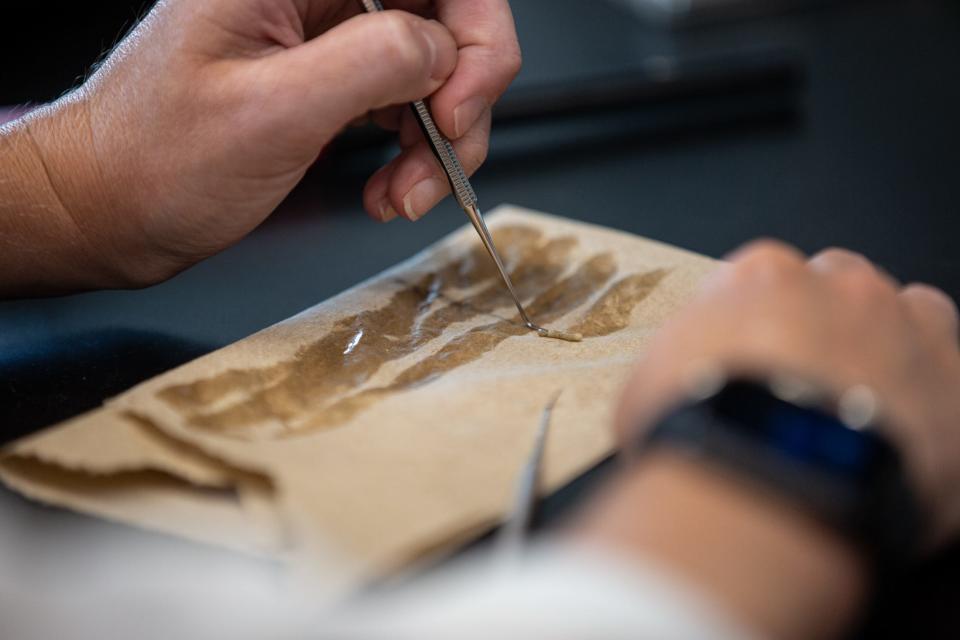

The community-based efforts rely on volunteers coming out, usually in the spring, to bag up recycled oyster shells in biodegradable mesh bags and then placing the bags in the water. The teams large-scale efforts involve a barge.

How to restore a reef

In St. Charles Bay, the team used recycled oyster shells from restaurants in Corpus Christi and Port Aransas through the Sink Your Shucks program.

“Oyster shells are the most important part of an (oyster) reef to provide the fundamental building blocks that little baby oysters need to attach to,” Pollack said.

The shells are stockpiled and sun-bleached for at least six months.

“Then we take them back out into the bay and put them back where nature intended,” Pollack said.

If the team doesn’t have enough shells stockpiled, it will lay down a base of crushed rock or concrete and then cover the base with oyster shells.

“The oyster shells are the natural reef-building material, so that’s what we really want to be exposed to the oysters that are in the water,” Pollack said. “That rock base kind of keeps it from sinking into the mud.”

Olsen said that many oyster conservation efforts in the state use limestone and river rock instead of shell. The Sink Your Shucks program is a rare example, Olsen said.

“Oftentimes, those shells are being sold off to different construction applications and things like that,” Olsen said. “They’re actually very valuable in that field. For the most part, for large-scale restorations we are typically relying on things like limestone or river rock and not so much on shell material.”

About a million pounds of oyster shell went back into the water in St. Charles Bay this summer due to the Sink Your Shucks effort.

“We’re working to actively grow it right now and bring new restaurants on board,” Pollack said. “Our hope is in the future we’ll have even more shells that we can put back into the bay when we do these big restoration projects.”

For the large-scale efforts, Rockport marine contractor Derrick Construction steps in. The construction company picks up shells from the Sink Your Shucks stockpile at the Port of Corpus Christi and transports them onto a barge to taxi the material to the mouth of St. Charles Bay.

Derrick Johnson is the director of operations at Derrick Construction Company.

“They’ve been doing these in sections from anywhere from four to eight reefs at a time,” Johnson said. “We’ll load up anywhere from 150 to 200 tons of rock and haul it out there.”

The shell goes down next.

Workers in the water check the elevation of the water and the restored reefs in the shallow waters. If the water is too shallow, the team uses excavators.

“It’s amazing to me, from what I have witnessed and seen through the years of building these things, how quick the growth is and how it becomes such a habitat,” Johnson said. “I mean, it blew my mind the first time.”

The oysters find the new habitat on their own.

“It’s sort of like 'Field of Dreams',” Pollack said. “If you build it, they will come.”

Texas A&M University-Kingsville program brings students back to campus to finish degrees

Youth environmental activist shares insights at League of Women Voters event

Corpus Christi Literacy Council offers skills and confidence for language learners

This article originally appeared on Corpus Christi Caller Times: Oyster conservation efforts see success in St. Charles Bay