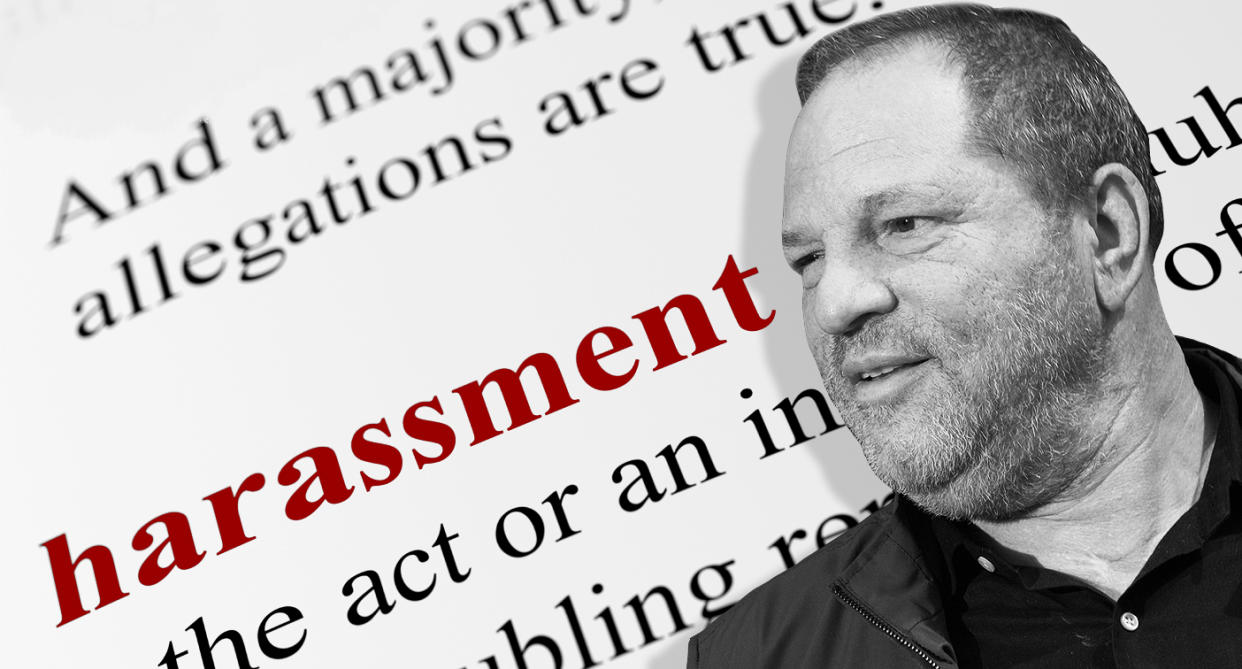

How Harvey Weinstein got away with it for so long

WASHINGTON — How did he get away with it for so long?

It is the vexing question at the heart of the Harvey Weinstein story.

The answer is simple and depressing: Nearly half a century after the start of rape law reforms pushed by second wave feminists and 31 years after the Supreme Court ruled that sexual harassment was a form of workplace discrimination prohibited by the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the legal system continues to struggle to provide justice for women who have been raped or otherwise sexually assaulted, except in the most extreme circumstances.

“Law & Order: Special Victims Unit” may have been inspired by the real-life New York City sex crimes unit, but the real-life odds that a woman who has been sexually assaulted will ever see the inside of a courtroom are low. On television, half the drama is accused criminals being held to account by prosecutors; in real life, most sex crimes never make it before a judge or jury, or even get to the point of an arrest.

This fact — complainants take on significant personal risks to their reputation and emotional well-being with only a small chance that their accused attacker will be prosecuted, let alone convicted — is among the reasons many women do not report sexual assaults, including rape, to police.

Only one woman is known to have lodged a formal criminal complaint against Weinstein before the recent revelations, just as one woman reported Bill Cosby to police. Both saw their cases dismissed by prosecutors as unwinnable. In this, their experience is the rule, not the exception.

Not every city has published a comprehensive look at how cases are handled in their jurisdictions. But those that have paint a startling portrait of how sex crimes are handled.

In Washington D.C., for example, only 10.3 percent of sex crime complaints received by police were prosecuted in 2015, and only 1.2 percent of the complaints led to guilty verdicts, according to a report prepared for the mayor’s office in 2016. There were 1,177 reports of adult sexual assault or crimes with a sexual element made to police — but just 14 guilty verdicts.

Another 4.4 percent of cases, 52 of the 1,177, were settled by plea bargains.

Nearly half the reports were not even classified as crimes by police or forwarded to prosecutors. Of the remaining 671 cases, only 189 involved arrests, and just 124 of those saw prosecutors move the case forward post-arrest.

In Virginia, only 37 percent of prosecuted sexual assault cases led to a conviction between 2005 and 2013 in the city of Newport News and Williamsburg-James City, and because such a small fraction of reported cases were prosecuted, “only 4 to 5 percent of incidents reported in those years have so far resulted in a conviction,” the Daily Press reported in May 2015.

One reason Washington, D.C., has tracked these crimes closely is that the city was, until recently, doing even worse. In 2013, Human Rights Watch published a report alleging that a large number of sexual assault complaints made to police were never logged or investigated. The Metropolitan Police Department contested the findings.

Other major cities have suffered similar scandals over the poor performance of their police departments and prosecutors in addressing sex crimes in recent years.

In New Orleans, the city’s inspector general released a report in 2014 concluding that only 14 percent of sex crime complaints sent to five special victims unit detectives were investigated. Of the 1,290 sex crime “calls for service” between 2011 and 2013, 65 percent were labeled as “miscellaneous” — marking them as noncriminal incidents — and no reports were taken. An initial investigative report was created for 35 percent of the calls. Of them, 271 cases were marked as crimes but not investigated past the initial report, and only 179 were further investigated.

That finding came on the heels of a 2011 investigation of the New Orleans Police Department by the Justice Department that found it “systematically misclassified large numbers of possible sexual assaults, resulting in a sweeping failure to properly investigate many potential cases of rape, attempted rape, and other sex crimes.”

Philadelphia police had come under fire for similar failures in the past, but by the 2010s had managed to reduce its unusually high percent of sex crime complaints judged “unfounded” — and thus kept off the crime statistics books — to a figure closer to the national average. In 2013, it was among cities praised by Human Rights Watch for “a victim-centered approach as opposed to one that emphasizes quickly closing cases.”

A Baltimore Sun investigation in 2010 found major undercounting in that city too. “The city has for the past four years recorded the highest percentage of rape cases that officers conclude are false or baseless of any city in the country, with more than 30 percent of the cases investigated by detectives each year deemed unfounded,” the paper reported. Additionally, “In four of 10 emergency calls that come to police for rapes, officers conclude that there is no need for a further review, so the case never makes it to detectives.” A follow-up audit presented to the city council found that half the discarded cases were misclassified and should have been pursued by investigators. By 2016, the Sun reported, the number of “unfounded” cases had dropped dramatically, but that didn’t always translate into them being investigated — let alone prosecuted — and across Maryland, the percent of cases deemed unfounded remained above the national average.

Nationally, the fraction of rape cases cleared by police was 36.5 percent in 2016, according to the FBI. That doesn’t mean the cases in question resulted in a conviction or guilty plea — only that the police, in most instances, made an arrest and handed the case over to prosecutors.

In Los Angeles, a 2012 Justice Department-funded study found a low prosecution rate and that the vast majority of allegations of rape reported to police did not end with the conviction of a defendant.

“We found that there is substantial attrition in sexual assault cases” presented to the Los Angeles Police Department and the Los Angeles Sherriff’s Department, the report concluded. “Among cases reported to the LAPD, only one in nine was cleared by arrest, fewer than one in ten resulted in the filing of charges, and only one in thirteen resulted in a conviction.”

When it comes to sexual assault overall, “the most reliable academic estimates of prosecution rates indicate that 14 percent to 18 percent of all reported sexual assaults” get prosecuted, the 2016 research report for D.C. concluded after surveying the data. That includes everything from misdemeanor assaults to felony rapes.

The most easily prosecuted cases, in D.C. and around the country, are stranger rapes involving weapons, injuries, and the rapid reporting of the assault to police. Cases of groping and non-penetrative sexual assault involving people who know each other — especially when they are not reported immediately to police — are less likely to be resolved by the legal system, except in the favor of the accused when police or prosecutors decline to act.

“In California, it’s sexual battery if it’s touching of the buttocks or sexual organs or breasts,” Los Angeles lawyer Karl Gerber, an experienced sexual-harassment litigator, told New York magazine’s Vulture site, discussing the Weinstein cases. “So that kind of stuff, somebody could be criminally prosecuted for. But it’s very, very rare that they go after these people criminally. I’ve had a lot of oral copulation cases, rape cases. I’ve never seen them get prosecuted. I’ve represented a lot of women that have been raped and they don’t even pursue that if it’s a workplace thing.”

In her experience with the office of Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance, Italian model Ambra Battilana Gutierrez met a justice system that rarely takes up complaints like the one she put forward in 2015 against Weinstein. Her experience in going to the police with a complaint that she was sexually assaulted and then having her case stall is more the rule than the exception.

“If we could have prosecuted Harvey Weinstein in 2015, we would have,” said Karen Friedman Agnifilo, the chief assistant district attorney for Manhattan, in a statement. She blamed the New York Police Department for failing to involve the Sex Crimes Unit in setting up the meeting between Weinstein and the model, who was recording him, so that prosecutors could obtain “what was necessary to capture in order to prove a misdemeanor sex crime.”

“While the recording is horrifying to listen to, what emerged from the recording was insufficient to prove a crime under New York law,” she said.

Meanwhile, Gutierrez’s name and face were splashed on the cover of the New York Post and her reputation dragged through the mud.

“Most rapes and sexual assaults against females were not reported to the police,” concluded the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics in an analysis of the question. “Thirty-six percent of rapes, 34 percent of attempted rapes, and 26 percent of sexual assaults were reported to police, 1992-2000.”

Those numbers have varied some over the years. “The percentage of rape or sexual assault victimizations reported to police increased to a high of 59 percent in 2003 before declining to 32 percent in 2009 and 2010,” according to a 2013 Bureau of Justice Statistics report. Overall, 36 percent of rape or sexual assault victimizations were reported to police between 2005 and 2010, and the percentage of reported incidents that were followed by an arrest decreased from 47 percent in 1994-’98 to 31 percent in 2005-’10.

Fear of retaliation and lack of faith in the police were the top two reasons women gave for not reporting their assaults, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, a prominent anti-sexual violence advocacy organization.

It’s no wonder that alternative and effectively private justice systems are proliferating.

One well-known and much discussed private justice system involves universities, which, following Obama administration guidelines, controversially began to adjudicate cases involving students using a different standard of proof – “the preponderance of the evidence” — rather than following the practice of the legal system, which requires finding guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt.” The Trump Education Department has rescinded the Obama rule and offered colleges the option of using the more stringent standard of “clear and convincing evidence.”

Another is the elaborate system of payoffs and nondisclosure agreements that Weinstein entered into to keep accusations out of the public eye.

Actress Rose McGowan in 1997 entered into a $100,000 settlement with Weinstein after an incident in a hotel room in Sundance when she was 23 years old. This week, she broke whatever nondisclosure agreement she may have signed and openly accused Weinstein of rape on Twitter. She is one of at least four women to accuse him of rape in the past week, as the number accusing him of all types of sexual assaults has grown by the day.

“Any allegations of non-consensual sex are unequivocally denied by Mr. Weinstein,” a spokesperson for Weinstein said.

As the number of women telling stories about Weinstein has mushroomed, the court of public opinion has turned decisively against him. He was fired from the company he built and helmed, and expelled from the Oscar-selecting Motion Picture Academy. As one-time collaborators and allies flee from any project he’s associated with, the future existence of the Weinstein Company itself looks uncertain.

At the same time, it’s early days of the scandal, and many men who have been accused of sexual assaults or improprieties with underlings in recent decades have been able to make comebacks or gone on to success in new arenas after disappearing from the public eye for a period.

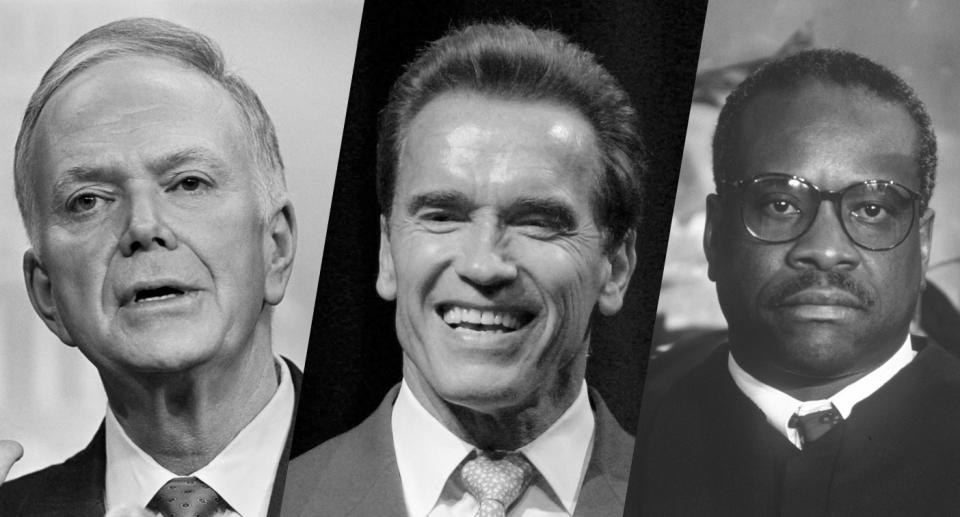

Sen. Bob Packwood was drummed out of office in 1995, more than two years after 24 women accused him of making unwanted advances or other sexual misconduct; Politico reported he found “redemption” and success as a Washington lobbyist. Arnold Schwarzenegger was elected governor of California despite a 2003 Los Angeles Times report that he groped at least six women. Clarence Thomas was confirmed as justice of the United States Supreme Court in 1991 after allegations he sexually harassed Anita Hill, covered at the time as a “he said, she said” story. Bill Clinton was able to rally Democrats in the 1998 midterm elections after his affair with former White House intern Monica Lewinsky became public, and amid a sexual harassment suit from Paula Jones that was a major news story during the election year. He eventually settled the case for $850,000, and in 2014 ranked as the most admired president of the past 25 years. Donald Trump was elected president of the United States after videotape surfaced showing him boasting about grabbing women “by the p****,” along with accusations of inappropriate sexual contact by more than a dozen women speaking on the record.

Former top Hillary Clinton aide Philippe Reines told Yahoo News that the Clinton campaign had considered running ads against Trump’s “Access Hollywood” comments, but found they didn’t move the needle.

“The campaign tested an ‘Access Hollywood’ ad, like, a few weeks after [the story broke], and they focus-grouped it and most of the room didn’t know what it was referring to,” he said in September. “Now that could have been a function of the ad being too subtle. But it was probably subtle because you didn’t think you had to be in your face with something like that. It was a warning sign.”

There is a lot of talk among Democrats these days about the “normalization” of the abnormal or abhorrent under President Trump, but when it comes to allegations of sexual assault, the norms deeply embedded in the legal system and the culture long predate the present moment.

And even men who are drummed out of public life and find their reputations in tatters on because of the breadth and extent of charges publicly made against them, like Cosby, they can nonetheless successfully fight it out in the formal legal system. When he was brought before a jury on an accusation of aggravated indecent assault in 2017, Cosby’s case ended not with a guilty verdict but with a jury so deadlocked the judge had to declare a mistrial. The accuser in the case, Andrea Constant, had initially filed a police complaint against Cosby in 2005, but her case was one of many prosecutors did not go forward with that year.

“There was insufficient, admissible, and reliable evidence upon which to base a conviction beyond a reasonable doubt. That’s ‘prosecutors speak’ for ‘I think he did it but there’s just not enough here to prosecute,’” Bruce Castor, a former district attorney in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, said in 2014, explaining his decision to not pursue a case against Cosby on charges of drugging and sexually assaulting Constant a decade ago. A new trial date has yet to be set.

Police in New York and London say they are reviewing their case files for additional reports about Weinstein, and the NYPD is reportedly looking into a just-filed complaint from a former actress and college student that Weinstein forced her to perform oral sex on him in 2004. But given how few sexual assault cases ever lead to convictions — not to mention Weinstein’s formidable resources, likely top-notch legal team and the length of time that has elapsed since the incidents — the American criminal justice system is likely to be the least of Weinstein’s problems in the months ahead.

Read more from Yahoo News: