I Was Supposed to Become an Ultra-Orthodox Rabbi. I Was Meant to Be Abby.

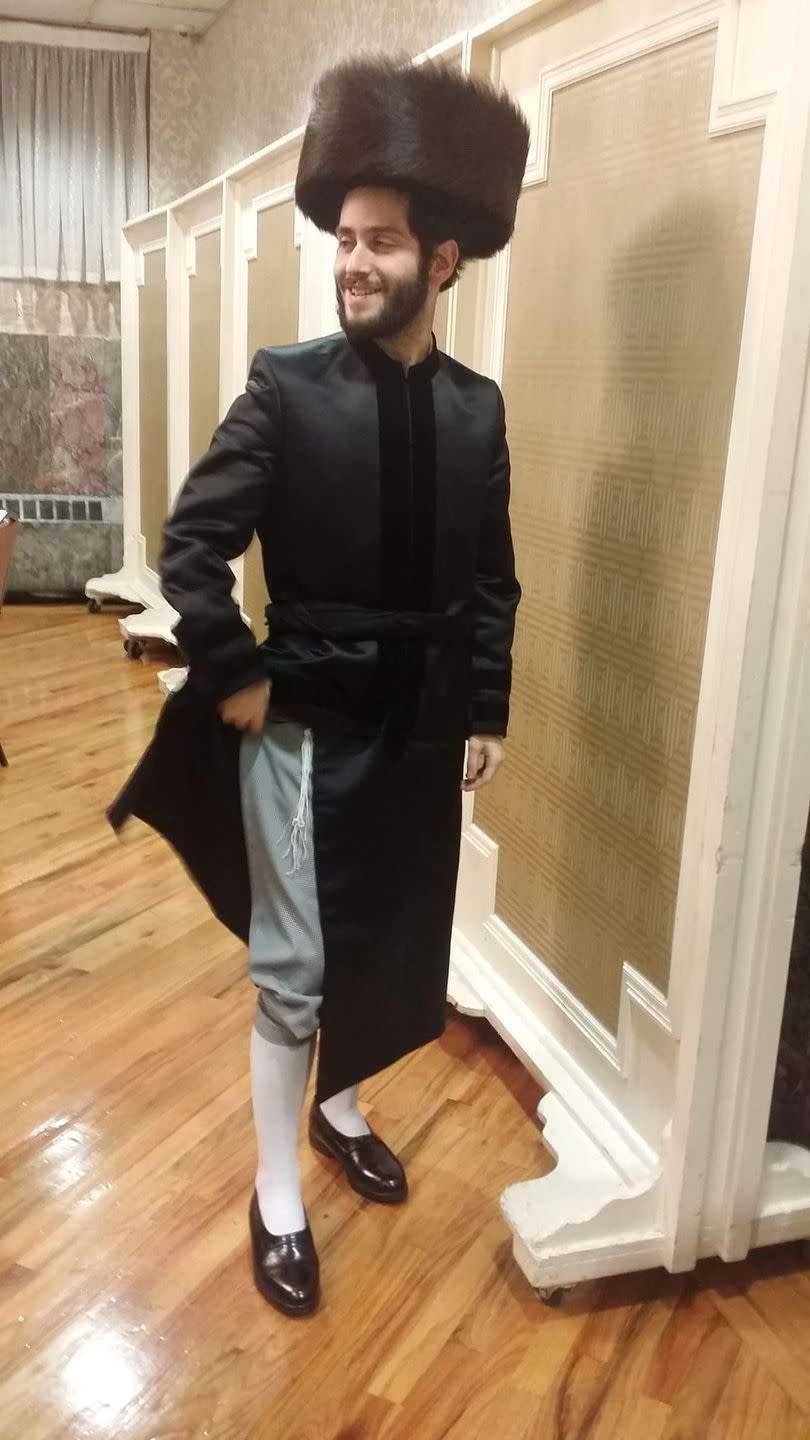

Abby Stein was born and raised in the Hasidic community of Brooklyn, New York, one of the world's most gender-segregated societies. As the first son in her family, and a descendent of the Baal Shem Tov (the founder of Hasidism), she was expected to live in accordance with religious law, marry at the age of 18, and become a rabbi. Stein, now 28, writes about rejecting that journey and coming out as transgender in her new memoir, Becoming Eve: My Journey from Ultra-Orthodox Rabbi to Transgender Woman.

I like to say I was geographically raised in Brooklyn, but culturally raised in 18th century Eastern Europe. My family lives in a Hasidic community, where they speak only Yiddish or Hebrew, and abide by a strict set of societal rules. Everyone dresses the same, follows the same life path, and does what they're supposed to do. I never quite fit that mold.

As a child, I loved trying on bright and colorful clothes, because they made me feel more feminine. I envied girls who played with dolls. When my parents cut my beloved long hair, I dunked my head in the bathtub hoping it would grow back, just like grass does when it rains. Once, I stabbed my penis with safety pins, wanting it to go away.

People in the LGBTQ+ community often talk about the "aha" moment when they realized or came to terms with their sexuality or gender identity. I never had that. For me, it was more like waking up to the fact that my family thought I was a boy. I always knew I was a girl, and every night I prayed to wake up in the morning looking like one.

My parents both descend from a well-respected rabbinical dynasty. One way or another, either by blood or by marriage, I'm related to every Hasidic rebbe, which is a kind of supreme leader in Hasidism. In order to continue the family legacy, my parents had my life mapped out for me before I was even born: I would grow "payos" (long side curls) starting at age 3, have my Bar Mitzvah when I turned 13, study to become a rabbi, and get married at 18. It's what was expected of me.

As a child, I pretty much wore the same thing every day: a dark-colored shirt and slacks. I was taught U.S. history in school, but it was heavily censored, and only versions the teachers wanted us to know. I was also completely sheltered from pop culture. I had no idea who the Beatles were. I'd never heard of Friends or Seinfeld. I've given up trying to watch, listen, and learn everything I missed as a kid.

In Hasidism, men are the leaders in all aspects of life. As far as I can tell, our community is one of the most gender-segregated societies in the United States. We had separate schools, buses, administrations, you name it. The wall separating men and women, both figuratively and literally, was so strong that it made it all the more obvious to me which side I belonged on.

My marriage to Fraidy was arranged by my parents when I was a teenager. I was excited about the prospect. I believed that once I got married, all the thoughts I had about my gender and my sexuality would go away. But, as I'd learn, it wasn't a disease, and there was nothing to go away. It doesn't work like that.

At Jewish weddings, we have chuppah, a canopy you stand under, and custom says the bride circles the groom seven times. As I stood under the chuppah at my own wedding, I thought: "I’m on the wrong side of this. I should be the one walking around." Being married opened up an entirely new world of femininity for me. I was able to speak with a woman who wasn't my sister or mother. I asked Fraidy what being a girl was like.

Three months after we got married, Fraidy got pregnant. I don't like to talk about our son, his life is private, but it was his circumcision ceremony that pushed me over the edge. I joined Footsteps, a support group for people who have left or want to leave a Hasidic community.

Six months later, Fraidy's family told her she had to leave me. In our community, marriages are both arranged and un-arranged. Fraidy told her family she didn't want to divorce. It escalated into a huge fight and an argument that lasted for hours. I haven't spoken to her since.

I lived with my parents after the divorce and got a job working for a packaging company doing online sales. My dad told me he would still support me even if I left the community. He hoped that if we stayed close, I would come back eventually. Now I know he saw me pulling away as a sickness, like having cancer. He wasn't supportive of me at all, but putting up with me.

I started taking gender studies and political science classes at Columbia University. I moved into a Jewish co-op and, for the very first time in my life, felt settled. I felt like everything was going to be okay, like I could dream. Today, I have a long list of dreams. I want to visit every country in the world—I've been to 40 so far. I'd also like to run for office one day. Maybe senator?

A post shared by Abby Stein (@abbychavastein) on Nov 12, 2019 at 2:42pm PST

I am who I am as a sum total of my experiences and I don't have any regrets. I give speeches about my journey and help run several organizations that help former Hasidic community members. In my spare time, I watch Heart of Dixie and Jack Ryan. I'm obsessed with books about New York City history. I have a loving group of friends. I'm currently dating someone. I'm an atheist, but I host Hanukkah celebrations at my apartment.

I don’t like to speak too much about the physical transition I'm undergoing. It's a lifelong journey for me, and it's private. When I did eventually tell my dad that I am a woman, he gave up on me forever. It was confirmation for him that I'd never I return to the community. I still try and talk to my parents, though they don’t pick up the phone. I’m hopeful they come around eventually. If there's a Hebrew translation of my book, I hope they'll read it.

Today, I'm happy—the happiest I've ever been—and that is because of, in spite of, and thanks to everything I've been through in my life so far.

You Might Also Like