I Haven't Spoken To My Family In Years. People Think I'm A Monster — Here's The Truth.

“Rescuing dogs and other animals in peril helped me overcome feelings of helplessness and abandonment,” the author writes.

On a winter’s night during which frigid Chicagoland temps and COVID boredom weighed on my brain in equal measure, I sat down at my laptop, typed in my mother’s name and the city where she lived, and then added the word “obituary” before pressing enter.

For many years, I had been performing this macabre search, and I always received the same answer: no results. I presumed it meant my mom was still alive.

This time was different. A single newspaper entry popped up. It said she had died two months ago. Two months ― and not one of my three siblings had called to let me know. I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised by that. I was the long-standing family outcast and hadn’t heard from any of them in years. Even so, I would have thought our mother’s death might have prompted one of them to pick up the phone and deliver the news to me. Though if I really believed that, why the internet searches?

The only other information included in the online announcement was a line about arrangements by a local cremation and burial service. No actual obituary had been written, so I wasn’t able to learn the cause of death, read a summary of my mom’s life that I imagine would have focused on her love of foreign travel and classical music, checked out a listing of next-of-kin (which I doubt would have included me), or learned when a service for her would be held. No memorial boards or online tributes been set up in her name either.

Had there really not been a memorial service or some other gathering to celebrate her life? As far as I knew ― though admittedly my knowledge was outdated ― my brothers and sister remained in contact with our mom and in fact were staunch defenders of her. Wouldn’t they have wished to honor her in some way?

I wanted to know other things as well. Had she been sick a long time? What did she die from? Was she still living at home at the time of her death? I contemplated reaching out to one of my siblings to get answers, but I stopped myself. Had they wanted me to know, they would have called.

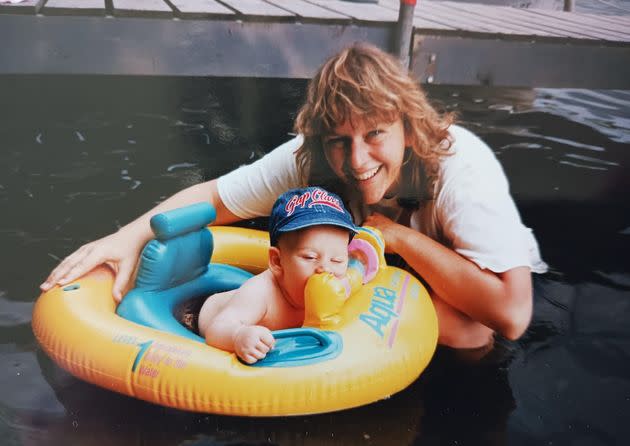

“The rift between my parents and me began with the birth of my son, pictured here at six months old,” the author writes.

Who could I share the news with? Only three people in my life had known all the details about my dysfunctional, stranger-than-fiction childhood. One had been my best friend of nearly 30 years, but she died unexpectedly eight years ago.

The second was my ex-husband. We’d been divorced for 15 years and though we were cordial enough, we had little to do with each other these days. We certainly didn’t share confidences.

The third was my mother-in-law. Now in her 80s, she had been slipping away into dementia for years. I doubted she would remember my mother — she might even have trouble knowing who I was.

I grabbed my phone and dialed my son.

“I have some kind of weird, sort-of-family news,” I said.

He didn’t miss a beat. “Has your mom died?” he asked.

“Yes.”

I didn’t need to worry that my son would be devastated by the death of his grandmother. Except for a brief, awkward meeting when he was eleven weeks old, he’d only been with my parents once, at a family wedding when he was 10. My mom and dad had been on their good behavior, as had I.

Afterward my son declared my parents to be nice people. I didn’t try to convince him otherwise. I was simply relieved that, against the odds, my family had gotten together and no blood had been shed.

In the days after learning of my mom’s death, I talked to a few of my oldest and most trusted friends about her passing. It was a short list. I’d learned from experience not to tell people that I didn’t have contact with my parents.

In the beginning, when our estrangement was fresh, I did tell friends. Inevitably, the expression on their faces, along with their body language, altered. They couldn’t help but look at me with great suspicion, as If I had done something terribly, terribly, wrong.

What kind of monster was I, that I had turned away from my parents?

“I was an awkward girl who had trouble forming bonds with classmates,” the author writes. “So, I escaped to a local riding stable where I forged friendships with horses. I remain enamored of them.”

The reason for the estrangement was equally difficult to talk about. For decades, I had unknowingly buried memories of childhood abuse at the hands of my parents. My amnesia began to lift within 24 hours of giving birth to my only child.

Suddenly I found myself facing a dilemma. My mother was getting ready to fly out to help me take care of my newborn. Now that I knew what she was capable of, I couldn’t allow her near my son. The rift began when I confronted my parents about my childhood trauma and canceled my mom’s visit. Soon after that, they ghosted me.

Now when I meet new people, I don’t bring up my family. If I can’t completely avoid the topic, I contain my remarks to the bare minimum, never disclosing the rift. If, over time, I feel more comfortable with someone, I might say something along the lines of, “My parents and I aren’t particularly close.” Even that disclosure can raise eyebrows.

I also don’t tell them that deep inside my psyche resides an absence ― a gaping void ― that nothing can fill. My life is missing all of the things that healthy families do together. They celebrate. Console each other. Grieve. Tell and retell the same old family stories and laugh or groan on cue no matter how many times they’ve heard them. I don’t have any of that and I deeply feel the loss.

Fifteen years after I was estranged from my parents, my dad died in Paris while on vacation with my mom. Out of the blue, she asked me to fly there and help sort out her affairs. I did so, hoping that what she really wanted was to reconcile. I could not have been more wrong about her motives. She wished to confess something to me: an unthinkable crime she’d committed. Once she did, she cut me off again — a betrayal that, considering what I knew about her, should not have wounded me afresh. But it did. That trip to Paris was the last time I saw her.

In his book “Fault Lines: Fractured Families and How to Mend Them,” Cornell University sociologist Karl Pillemer estimates that 27% of Americans are estranged from a family member, and he thinks that number might be low because people are reluctant to talk about it.

Why shouldn’t we be reticent? To most people, the words “mother” and “father” are sacred, mythic in their significance. Our parents are the people we’re supposed to love and trust the most — the first we turn to when we need advice or a shoulder to cry on. To have no contact with them, the ones who brought us into this world and who’ve stuck with us every step of the way? Inconceivable.

"As it turned out, forgiveness was a wonderfully selfish act that freed me from my pain and anger, and allowed me to move on," the author writes.

So I stay silent on this topic, which, like all taboo subjects, carries with it a heavy load of shame and stigma. Even if wanted to unburden myself, it’s too disturbing to others who, upon hearing such alarming news, feel as if the floor beneath them has suddenly given way. They don’t know how they would survive without their parents.

However, it is possible to not only survive estrangement, but to thrive despite it. We humans are tribal, and our well-being requires close connections with others. When our birth family isn’t there for us, we can learn to build a network of what I call our true family — people who though they’re not related by blood, nevertheless love us and would do anything for us, just as we’d do the same for them. Starting our own families and vowing that our kids will grow up knowing how much they’re loved and treasured is another way to both stay connected to others and also heal from the past.

As I’ve gotten older and no longer guard my emotions so zealously, I find myself crying more easily and frequently. But when I learned of my mother’s death, I didn’t cry. Not because I’m cold. The fact was, I’d already spent decades of my life shedding tears over her — mourning the loss of her while she was still alive.

Somewhere along that long and twisted road, I’d learned to forgive her. That took time. For many years, I thought forgiving meant pardoning or even condoning her past behavior, and I couldn’t do that. As it turned out, forgiveness was a wonderfully selfish act that freed me from my pain and anger, and allowed me to move on.

Other than hoping my mom hadn’t suffered too much in her final days, there was little for me to do or consider after learning she was gone. I did remain curious about how she’d died because the cause of her death was now part of my own health history. Online, I found the website of the vital statistics bureau in the state where my mom had lived and requested her death certificate. I learned that a notification that included cause of death could only be issued to a family member.

To get a copy, I would need to provide proof of my identity and explain what my relationship to the deceased was. I typed in “daughter” and then stared at the word. In the strictest legal sense that label was true. But in the ways that matter and in the inner workings of my heart, I was no longer my mother’s daughter.

Constance Gray’s features and essays have appeared in Minnesota Monthly, Austin American-Statesman, Minneapolis-St. Paul Magazine, Isthmus Magazine, Catholic Digest, City Pages, Wisconsin State Journal and the St. Paul Pioneer Press. She is currently putting the final touches on a memoir about family dysfunction and estrangement titled “Six Days in Paris.” You can reach her at crystaltara108@gmail.com.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.