Hazardous sinkholes are common in parts of Pennsylvania. Here’s what to look out for

Note: This article was first published Feb. 22, 2023, following a sinkhole last winter in Patton Township. We’ve updated it with the latest on a sinkhole on Penn State’s campus.

A parking deck on Penn State’s University Park campus was evacuated Wednesday due to hazardous conditions stemming from a sinkhole.

The temporary closure came as a result of “an abundance of caution,” university officials said. By 2:30 p.m., some permit holders were receiving assistance removing their vehicles from the parking deck, though other vehicles may not be able to be removed “due to safety concerns.”

Sinkholes are not an unheard-of occurrence in Pennsylvania. The commonwealth’s geologic profile lays the groundwork for subsidence, or the sinking of the Earth’s surface in response to natural or human-induced causes, often through sinkholes or erosion. Today, sinkholes remain a definitive characteristic of the Keystone State’s unique geologic landscape that has developed over hundreds of millions of years.

From their root causes to countless complications, here’s what you should know about sinkholes in Pennsylvania.

What is a sinkhole?

Generally speaking, a sinkhole is a hole or depression in the ground that forms after moving water slowly dissolves surface rock and collapses a portion of the surface layer. While that process can occur slowly over time, sinkholes may collapse inward very suddenly and without much warning.

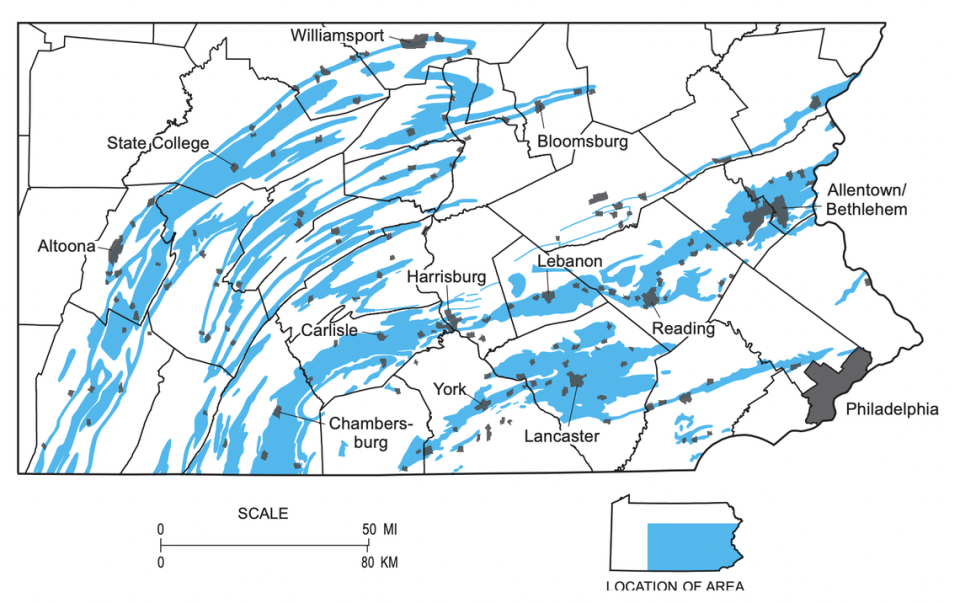

Sinkholes are most commonly found in areas underlain by carbonate bedrock, a specific class of sedimentary rocks composed primarily of easily eroded carbonate minerals. In Pennsylvania, that’s mostly limestone, which is found prominently in the commonwealth’s central and eastern regions. It’s no wonder Pennsylvania is one of the most common locations for sinkhole development in the country, according to the United States Geological Survey.

Landscapes characterized by dissolving bedrock and sinkholes, caves and springs are sometimes referred to as karst landscapes, according to U.S. environmental officials. Across the country, these landscapes form when water interacts with surface material and enters the subsurface before slowly dissolving bedrock.

Rocks that easily dissolve are the driving force behind sinkholes in Pennsylvania. Richard Alley, Ph.D. and leading Penn State geology professor, says sinkholes are especially common in the low-lying valleys between mountains, just like those near State College.

“Central Pennsylvania is overrun with sinkholes. There are lots and lots of them around here,” Alley said. “If you live in a place where the rocks do not dissolve easily — up on mountain ridges or in much of the world — a hole will fill with dirt, and, eventually, a stream flows over the top and keeps water moving much like a river, unlike a lake… If the rocks dissolve and make caves, especially with the limestone we have here, the top might fall in and result in a sinkhole.”

While sinkholes have dominated local headlines this year, they’re nothing new. The commonwealth’s geologic history, which stretches back for hundreds of millions of years, gradually paved the way for hazardous subsidence features thanks to a large buildup of sedimentary rocks.

The bulk of those rocks, largely limestone and dolomite, can trace their roots back to Pennsylvania’s days as an ancient ocean, Alley says.

“The long story is that when the Appalachians were being formed, you had this big mountain range that formed to the west of us, and that weighed down the [Earth’s] crust a little bit and bent it,” Alley said. “We were a shallow seaway for a long, long time... Old sea deposits, and there are a lot of them here, commonly produced sedimentary rocks that dissolve more easily.”

“It is ultimately the geologic underpinnings of Pennsylvania, complete with rocks that are great for making caves, that give the commonwealth its notable sinkhole risk,” Alley continued.

Sinkholes in the State College area

Although Pennsylvania’s geologic history spans millions of years, the effects of the commonwealth’s development are still seen today.

A good example of a sinkhole in Happy Valley is the State College Area School District’s Memorial Field, best known as the home of the Little Lions high school football team. According to the district, the project originated as a Work Progress Administration initiative that turned an infamous sinkhole into a community fixture that has now lasted for nearly a century.

Since its development in the years following the Great Depression, Memorial Field has undergone several refurbishment projects and modifications to account for growing demand and continued flooding, among other sinkhole-related problems. The facility recently received a $14.3 million face-lift in 2020 that improved locker rooms, bleachers, restrooms and concession stands. Previous work helped repair portions of the stadium affected by subsidence, according to the school district.

“Why do they spend all that money to fix Memorial Field? Because it tends to flood. And why does it tend to flood? Well, because it’s in a hole,” Alley said. “There are lots and lots of natural sinkholes in our area, and some come with baggage for residents.”

Sinkholes grabbed public attention last winter when 20 State College-area townhomes were deemed unsafe in late December and January after a sinkhole opened up in a Patton Township parking lot. Centre County officials met in July and approved emergency funding to assess and repair a different sinkhole that unexpectedly opened up in the county sheriff’s department’s west parking lot.

From Alley’s point of view, sinkholes and their related features are significant factors behind local development. Nearby towns like Bellefonte, for example, can trace their origins back to nearby springs that originated from subsidence features, while regional landmarks like Penn’s Cave were formed through dissolving rock beneath the surface.

Even Penn State’s founding can be credited in part to the nearby Thompson Spring, named after two of the former owners of the historic Centre Furnace, which planted itself near the water source just off what’s now College Avenue. In 1855, James Irvin and Moses Thompson donated approximately 200 acres of Centre Furnace land to help establish the Farmers’ High School of Pennsylvania, which would later become Pennsylvania State University.

“Geologic events like sinkholes and caves and so on present a lot of hazards if you happen to fall into one, but they’re also why we’re here in the first place,” Alley said.

How can sinkholes affect my community?

Outside of naturally occurring sinkholes, those caused or accelerated by human activity can pose significant risks for homes and local infrastructure.

Poor storm-water drainage can be a large factor behind sinkhole development in urban areas, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. After roads are paved and utility lines are laid, less soil is available to absorb water following heavy rain, potentially adding stress to drains that are working overtime to properly function. Poor drainage beneath the surface can amplify rock dissolution.

Broken or poorly maintained utility lines beneath the surface can also contribute to the development of sinkholes. Infiltrating water can gradually cause subsidence and, in extreme cases, prompt an eventual collapse, opening up a sinkhole visible from the surface.

Naturally occurring groundwater can also contribute to sinkhole development when human activity gets in the way, Pennsylvania officials warn. Such an occasion arises when groundwater is pumped out of quarries or mines.

Curious if a landscape feature is a sinkhole? Keep the following pointers in mind, courtesy of the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources:

How old is the site? Holes or depressions in the surface often accompany construction when soil is deposited or redistributed or when trees are uprooted. A true sinkhole is generally the product of slow, gradual buildups beneath the surface.

Wet surface areas do not necessarily imply the existence of a clogged drain beneath the surface. For instance, construction can radically change landscapes and alter the flow and gathering of surface water.

Is the hole an animal burrow? They are typically small and accompanied by ejected material, like soil and rock, that an animal removed from the hole while constructing it.

Is the site an old mine? Underground mining is a common factor behind sinkhole development. Consider consulting local resources, like historical records or libraries, to learn more about the history of your property and neighborhood.

When sinkholes do occur, it’s important to observe the following safety precautions, Pennsylvania officials say:

Securing the area around a sinkhole is critical. Fencing and warning markers can help keep curious minds away from dangerous sites. Local authorities can help secure large sinkholes.

Sinkholes should not be entered regardless of how safe they might look. Activities like spelunking or cave diving are best left to trained experts with proper equipment.

Notify local gas companies immediately if a sinkhole occurs near a home or business that uses natural gas. A disturbance to a gas line can prove dangerous and costly.

Gather as much data about your property, utilities and structures to assess the damage, potential complications and safety threats.

How State College firefighters rescued Frederick, an ‘extremely friendly’ corgi, from a sinkhole

Sinkhole repairs are often costly and complicated and, typically, are best left for properly trained crews. The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection maintains a list of best practice documents online. Repairs typically require the closure of the sinkhole and the removal of the triggering mechanism.

Want to learn more about sinkholes in your neighborhood? Visit the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resource’s online interactive map at www.gis.dcnr.state.pa.us/pageode/ to browse local data points and examine local surface depressions.

Who is liable for sinkhole damages?

Generally, standard homeowners insurance policies do not cover damage caused by sinkholes or other Earth movements, including earthquakes or landslides, the Pennsylvania Insurance Department says. In some states, including Florida and Tennessee, insurers are required to offer optional protections, including policies that cover sinkhole damages.

In Pennsylvania, those who wish to add sinkhole insurance may need to purchase specific coverage as add-ons.

Sometimes, sinkholes may form or worsen as a result of quarry pumping or activity. Such instances should be reported to the DEP’s district mining office in your county.

When sinkholes are not the result of DEP-regulated activities, the department is not legally obligated to assist landowners with repairs or recover costs associated with sinkholes. Landowners are ultimately responsible for sinkhole repairs on their property, the department said.

Note: A previous version of this story included a correction on the reported cause of the Amblewood Way sinkhole.